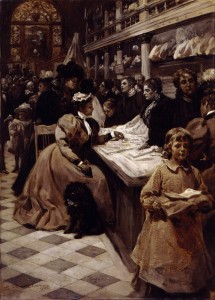

Alice Barber Stephens (1858-1932)|The Woman in Business, 1897|Cover illustration for The Ladies Home Journal (September 1897) for series on "The American Woman"|oil on canvas|Collection of Brandywine River Museum, Museum purchase, 1982|Acquisition made possible through Ray and Beverly Sacks. Accession number, 82.12

A. T. Stewart’s 1846 “Marble Palace” department store in New York was the first to open in this country. By the 1890s most major American cities had department stores which provided access to a cornucopia of goods made at home and abroad. In addition to being emporia where every mercantile desire could be satisfied, department stores were places where respectable women could earn a living. In Alice Barber Stephens’ illustration The Woman in Business, created as a cover for The Ladies Home Journal as part of a continuing series of articles on “The American Woman,” we see images of working women as well as consuming women with the gulf of the display counter clearly separating the two worlds.

United States census information comparing occupations for women from 1870 through 1920 indicates that over those decades decreasing numbers of women worked as servants while increasing numbers of women worked in clerical professions, which includes salesclerks.* As indicated in Stephens’ illustration, there were a few men who worked behind the counter. Some men were sales clerks, but they also were managers of the women. The growing abundance of clerking positions for women offered liberation from jobs requiring greater physical labor and shifted females into slightly more respectable positions in society. Department stores provided another place where upper class women could go to enjoy their leisure—a place where it was acceptable for women to be seen in public pursuing activities without a chaperone.

Stephens’ cover composition reveals some labor issues of the day. While seats were provided for customers (indeed one is shown seated with her dog at her feet) the sales clerks stand on the other side of the counter. Sales clerks were forbidden to sit while on duty and were often fined if there were seen sitting down.** Those fines would be deducted from the women’s paycheck. As a condition of employment, department stores often demanded that women workers be unmarried. It was felt that women should not take employment from a man since he was typically the provider of funds for his family.

Compare the privileged look of the hated and beribboned child accompanying her shopping parent in the illustration’s background, to the foreground child carrying shop goods and wearing a plain dress covered by a full apron. She is working as a runner or gopher. At the time of this illustration, there were no national child labor laws in the United States. It is not until 1904 that a national campaign for child labor law reform begins and not until 1938 that the minimum age of employment and hours of work for children are regulated by federal law.

Notice the delineation of an elaborate decorative stained glass window in the far left background of this illustration. Turn-of-the-century department stores were often fitted out with grand spaces and elegant decorations. Wanamaker’s in Philadelphia had a “Crystal Tea Room” and A. T. Stewart’s had a department that was an art gallery. The inclusion of an expensive and elaborate stained-glass window in a department store would imply that it was someplace very special, like a church, library, or palace. No wonder department stores have been called palaces or cathedrals of consumption.

Stephen’s Ladies Home Journal cover illustration was painted in black, grey, and white tones, called en grisaille. While photomechanical method of reproduction of images was growing more common in the 1890s, it would take until the 1920s for photographic reproduction equipment to perfect a three-color separation process.

*Joseph A. Hill, Women in Gainful Occupations, 1870 to 1920: Census Monographs IX (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1929): 39.

** As early as 1875 committees of ladies petitioned to abolish the rule forbidding shop-girls to sit during their hours of employment. See, “The Shop-Girls” in the New York Times (December 15, 1875).

October 22, 2009

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum