Lynn Buckham (1918-1982)

If you believe the images created for magazines and advertising illustrations in the third quarter of the 20th century you would think that all women from that time were beautiful; they always dressed impeccably; their waists were universally cinched; their hair was always perfect and their lipstick never needed to be freshened. Men in these illustrations were always tall and handsome; and that sexual tension between men and women was everywhere. Since I was a young girl and then a women during this period, I can verify that those images were more often illustrator’s illusions than not. On the other hand, men are wonderful.

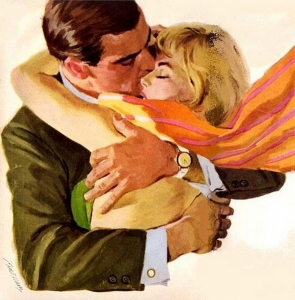

Jon Whitcomb (1906-1988)

Cover illustration for Cosmopolitan (March 1958)

Oil on canvas

So what pushed this proliferation of picture perfect women and their male counterparts? American and British post-war optimism married with the quickly proliferating television programming along with the movie industry fed the populace unequaled unending pictures of perfect pulchritude. And because these fictions were meant to give us a view into the desires of our secret-selves, we bought these fantasies as another reality. The visual perfection of Jack and Jackie Kennedy in photos and on the television only made the fiction more real. No doubt that is why many of us love watching the 21st century TV program, Mad Men where we see these fictions reinforced.

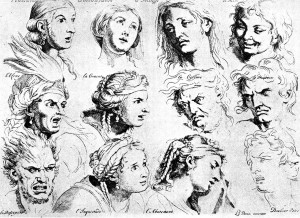

Hugh J. Ward (1909-1945) Charles Lebrun (1616-1690)

The Evil Flame, 1936 Physiognomy Studies, c. 1663

Cover illustration for Spicy Mystery Stories

(August 1936)

Oil on canvas

It is interesting that voluptuous women of the pulps from the previous decades could trespass on the titillating because they were not meant to be viewed by a general audience. But neither pulp images of women nor the contemporaneous pin-up pix focused on the later 20th-century absorption with picturing people’s emotional states and relationships between the sexes. The interest in visualizing emotional states had long been a focus of artists who wanted to paint convincingly. Indeed even Hugh Ward’s pulp magazine cover illustrations (see one above) reflect the understanding of how to visually reveal fear and horror. More than 300 years before, the French academic artist Charles Lebrun drew a variety of demonstration faces cataloging aspects of facial change depending on the emotion reflected in a face.* It was not until the late 19th century that painters attempted to picture less visually distinctive activities such as contemplation or introspection.

Will R. Barnet (1911-2012)

Introspection, 1972

Serigraph

RoGallery

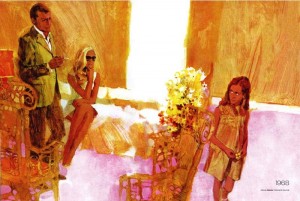

Along with the growing acceptance of psychoanalysis in the 1960s came an increasing reflection of women and men’s shifting roles in popular culture images. And even more important, images and their stories begin to reveal the questioning emotional reality of many women’s lives. Indeed it is the shifting life-styles and women’s expectations for themselves that seems to be reflected in the changing focus of illustrations and their stories in late 1960s women’s magazines.

In 1967 illustrator Bernie Fuchs told an interviewer that the hardest part of working as an illustrator was, “Getting the idea, that’s the hard part. I try to find the thing in the story—whether it is an incident; a portrait of a character, a symbol or whatever—that I feel is most worth translating into a picture. My aim is not merely to decorate the page but to make illustrations that will contribute to, and perhaps heighten, the meaning, drama and emotion of the words.”**

It would seem that the disquiet between the rising hippie culture in the late 60s and early 70s and the preceding decade’s consumers of TV and magazine versions of middle American women such as the television characters Harriet Nelson, Margaret Anderson, and June Cleaver, was a comparison of similarities versus differences. Easily noticeable styles of dress and adornment were a quick way to represent either the supposed cultural norms of the late 1950s and early 1960s or the wilder freedom of the counter culture. But instead of focusing too closely on the decorativeness of counter culture garb or writing fiction about the social and political stresses that were beginning to pull us apart generationally and culturally, popular magazine and story imagery took readers to the world inside. It is as though the angst of stories like Carson McCullers’ 1946 novel, The Member of the Wedding, finally found a foothold in the nation’s post-war psyche. A story’s theme, gender and race identity, and society’s expectations of gender and race expressed the frisson between hope and hopelessness that drew some of the story lines we found in popular magazines in the late 60s and 70s. The result was a shift in pretty women imagery toward illustrations of loneliness, defiance, or introspection, where color, spatial organization, and construction of the gaze (as seen in the illustrations below), reinforced the story’s theme.

Bernie Fuchs (1932-2009) David Grove (1920-2012)[Waiting Up] [Family Discussion]

Story illustration Good Housekeeping Story illustration for Woman’s Journal (1968)

(March 1967)

* Charles Lebrun’s theory of expressing passion in a drawing or painting was posthumously published in 1698 as Méthode pour apprendre à dessiner les passions. Norman Rockwell, like other artists, often looked at his own face in a mirror in order to make certain his characters would convey his intended emotion or state of mind.

** Mary Anne Guitar, “Portrait of an illustrator: Bernie Fuchs” in Famous Artists Magazine v. 15, No. 4 (Summer 1967): page 8.

*** Harriet Nelson played herself on Ozzie & Harriet, Jane Wyatt played the family’s mother, Margaret Anderson in Father Knows Best, and Barbara Billingsley played the family’s mother, June Cleaver, in Leave it to Beaver.

May 1, 2014

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum