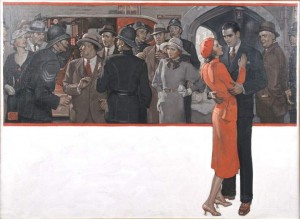

Ralph Pallen Coleman (1892-1968)|An Atlantic Adventure, 1933|Illustration for “An Atlantic Adventure” story by Diana Bourbon in Cosmopolitan (August 1934)|Oil on canvas|Collection of the Society of Illustrators, donated by Ralph P. Coleman, Jr., 079.017

Ralph Pallen Coleman was a native of Philadelphia and a graduate of the Philadelphia College of Art (then part of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and now an independent university called The University of the Arts). His first published illustration appeared in the Saturday Evening Post in 1915. He went on to illustrate many more magazines and books including this image for a transatlantic story in Cosmopolitan magazine.

The story is of a thoughtless reporter who has been fired from his job and who stumbles across a mystery involving the murder of the District Attorney. Pursuit of the guilty parties takes the adventure onto a cruise ship and then to England. In 1935 this story was turned into an hour-long black and white movie. The story’s author, Diana Bourbon, would subsequently work with Orson Welles and the radio players of the Mercury Theatre. In addition to her radio directing, she would also be a bit-player actor, for example, as one of the gentry’ crowd at the Ascot races in the 1964 film version of My Fair Lady.

While the above might seem like a bit of a wander off the topic, it is an interesting comparison. Remember how Director George Cukor, during the production number of Lerner and Loewe’s Ascot Opening Day, slides the camera and then stops as the scene progresses and the cast sing and strut? It seems to me that Ralph Coleman used a similar cinematic construction to Cukor’s slide and stop camera action for the image for “An Atlantic Adventure.” He divided the canvas in half horizontally with a red line marking the middle, so that the crowded British street scene is above the line and the central characters of the story, the quietly embracing couple, stand in the white of the lower half of the painting. A second red line marks the top edge of the image. The couple are separated, indeed are emphasized by standing in the white of the lower half, even though their upper torsos overlap the upper portion of the painting. They are both set apart and embraced by the action of the scene as though they are two people alone in the crowd despite the commotion on the street around them. This technique makes it easy to spot the important characters in the illustration. Or does it?

If you look closely at the upper portion of the illustration, it appears that that too is divided into two sections. The portion to the left of the embracing couple has all the action facing outward toward the viewer, and most of the characters looking at the man in the beige suite and orange tie as he is being confronted by a pair of bobbies (English police men) who face back into the scene and are beginning to confront the central man. The second portion of the background scene is constructed to the right of the embracing couple and is composed of only two characters: a bobby and the man in the beige suite whose hands are behind his back (secured?). The captured man and the bobby look back at the embracing couple. To help to define the two-part nature of the background action, Coleman created two different openings in the painted brick background wall. The right opening is a gothic-style pointed archway that leads through a short tunnel to another bit of landscape glimpsed through the passageway. The second prospect at the left of the painting is edged with a more modern shiny molded metal edge and through its opening a side view of a cab and the back another vehicle may be seen.

The painting’s restricted color scheme doesn’t limit the image. Instead it helps to reinforce the illustration’s cinematic quality: as though we are viewing images sliced from a movie. It makes me wonder when the decision was made to transform Diana Bourbon’s story into a movie. Did Coleman’s illustration aid in that decision, or was it reflective as a decision already made?

March 11, 2010

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum