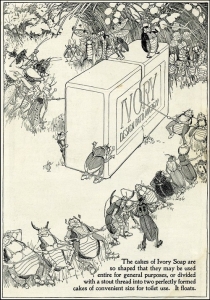

Proctor and Gamble Company of Cincinnati first sold Ivory Soap in 1879. As you can see in the ad here on the right, early advertising illustration was produced in a minimalist way and from a purely practical aspect—so what you see is a pair of hands use a thread to divide the double-sized bar soap at the processed demarcation.

Proctor and Gamble Company of Cincinnati first sold Ivory Soap in 1879. As you can see in the ad here on the right, early advertising illustration was produced in a minimalist way and from a purely practical aspect—so what you see is a pair of hands use a thread to divide the double-sized bar soap at the processed demarcation.

Walter Harrison Cady (1877-1970) Unknown artist

Ivory Soap, early 1900’s Ivory Soap, 1882

Advertising illustration for Proctor Advertising illustration for Ivory Soap

and Gambles’ Ivory Soap appeared in The Independent (December 1882)

By 1896, the company ran its first color print ad in Cosmopolitan Magazine. Soon after they began hiring various illustrators such as W. Granville Smith, J. C. Leyendecker, and Jessie Willcox Smith, to produce their advertising illustrations. Among their amazing ads only one is by Walter Harrison Cady (see above). It is an illustration of two opposing tug-of-war groups of bugs and beetles standing in a clearing pushing and pulling a thread through the cake of Ivory Soap. What strikes me most about this illustration is that troop of insects is perfectly fitted out in period appropriate clothing and wearing shoes. They even hold onto the thread with their visibly articulated hands.

I have long been enamored with illustrations of anthropomorphic animals. Besides common fairy tales and Aesop’s Fables there is an assortment of other illustrators and cartoonists who have created their images with animals and insects standing in for human characters. Most notable are Joel Chandler Harris’s rewritten plantation stories first published as newspaper columns in 1876 and as a book in 1880 called Uncle Remus: His Songs and His Sayings. Harris’s character Uncle Remus told stories of anthropomorphic animals lifted from the African American oral storytelling tradition. Various versions of Harris’s books were illustrated with animals in clothes drawn and/or painted by such illustrators as Arthur Burdett Frost for the 1895 version of the book (see below) and the more contemporary version retold by Julius Lester and illustrated by Jerry Pinkney (see below). Clearly the illustrator’s skill at producing realistic images of animals is remarkable. But just as fabulous is their ability to convincingly clothe the anthropomorphic animal as well as the human characters (in Pinkney’s example) so that images with their interaction feel real.

Jerry Pinkney (b. 1939) A. B. Frost (1851-1928)

Brer Rabbit and Miss Nancy, 1994 Brer Rabbit, 1892

Last Tales of Uncle Remus, retold Uncle Remus and His Friends

by Julius Lester (New York; Boston: (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1892)

Dial Books, 1994) Sterling and Francine Clark Art

Watercolor and pencil on paper Institute

Collection of the Artist

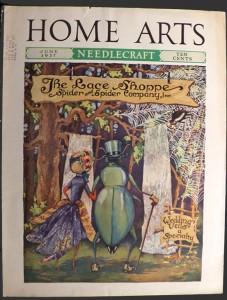

Marjorie P. Rowell (??)

Shopping for the Wedding, 1937

Cover illustration for Home Arts (June 1937)

Marjorie Rowell’s above cover illustration for Home Arts magazine from June of 1937 shows two well-dressed insects (a dragonfly and beetle?) shopping for a wedding veil at Spider and Spider Company, Inc. The Lace Shoppe. Notice how the hard shell of the beetle’s back becomes the back of a tailcoat (also called a cutaway) and the transparent wings of the dragonfly morph into the transparent overskirt of the lady’s dress. Her head is not big and round—that is the back of her summer straw hat.

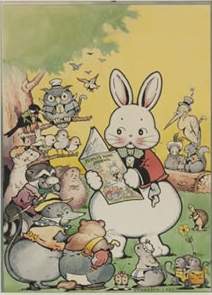

W. Harrrison Cady (1877-1970)

Peter Rabbit and His Friends

Cover illustration for Peoples Home Journal

Watercolor and ink on paper

Private Collection

As much as I love Cady’s Ivory Soap ad (at the beginning of this essay), he was perhaps best known for his Peter Rabbit newspaper cartoons beginning in 1920 and for Thornton W. Burgess’s Peter Rabbit illustrated story books. Burgess’s Peter Rabbit is not the same as the one in Beatrix Potters’ stories.

In the above colorful magazine cover Peter Rabbit stands holding a copy of the magazine in his hands with a masthead that reads, People’s Home Journal.* The picture on the cover of the magazine is the same as the picture we see with the rabbit holding the magazine.

Peter Rabbit wears a red jacket with black trim at the cuffs and on the lapel. His bowtie is a white pattern on a delicate green fabric, and between the lapels and under the tie we see a shirt button and what appears to be the edge of a vest. Poised in a rough circle around Peter Rabbit are a Momma chipmunk wearing a mob cap and a white apron and she pulls a wagon with three little chipmunks inside. The other clothed characters in this scene include a ladybug wearing shoes, a bear, an opossum, a raccoon, a ferret, a crow, an owl, a squirrel family and a stork with a top hat, an umbrella, and wearing glasses.

If you compare Cady’s rabbit with those drawn by Frost and Pinkney, you can see that in both examples of Brer Rabbit his body conforms to nature, and the clothing Frost and Pinkney imagined for the animal’s body conforms to a rabbit’s anthropomorphic reality. Which is not to say that I don’t love Cady work. For me it is Pinkney and Frost’s conformation to reality that is what makes their illustrations special.

* People’s Home Journal was a monthly magazine meant for housewives and women and was published from 1886 through 1929. Although I’ve only seem a partial run of this magazine, there are three known anthropomorphic cover illustrations by Cady for this magazine: March 1927, October 1927, and February 1928.

April 17, 2014

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum