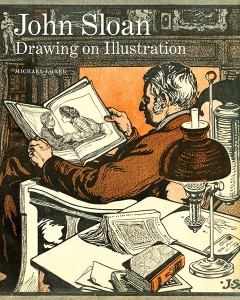

In John Sloan: Drawing on Illustration, my new book from Yale University Press, I use the work of Sloan—an early twentieth-century American artist and member of The Eight and the Ashcan School–as a lens through which to consider the subject of illustration more broadly. As such, while the book focuses primarily on the several decades around the turn of the twentieth century, I repeatedly link this historical content to matters closer to our own time. For instance, I relate the growing obsolescence of newspaper illustrating around 1900, which was spurred by refinements in photographic halftone reproduction, to a similar eclipsing of photojournalism today (since, in a world in which there’s a camera in every phone, every one of us is potentially a documentary photographer); and I discuss how blogs and online discussion forums are still buzzing with debates about the appropriation of popular images by fine artists from decades ago, such as Roy Lichtenstein’s 1960s Pop art borrowings from comic books. Similarly, if the book takes one artist as its main subject, it simultaneously touches on a wide range of figures—from Charles Dana Gibson and Robert Henri to Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol—while tracking the longer historical trajectory of illustration, including a section of the introduction, titled “What is Illustration?” that puts forth a list of the constitutive characteristics of illustrating as a modern visual form.

In John Sloan: Drawing on Illustration, my new book from Yale University Press, I use the work of Sloan—an early twentieth-century American artist and member of The Eight and the Ashcan School–as a lens through which to consider the subject of illustration more broadly. As such, while the book focuses primarily on the several decades around the turn of the twentieth century, I repeatedly link this historical content to matters closer to our own time. For instance, I relate the growing obsolescence of newspaper illustrating around 1900, which was spurred by refinements in photographic halftone reproduction, to a similar eclipsing of photojournalism today (since, in a world in which there’s a camera in every phone, every one of us is potentially a documentary photographer); and I discuss how blogs and online discussion forums are still buzzing with debates about the appropriation of popular images by fine artists from decades ago, such as Roy Lichtenstein’s 1960s Pop art borrowings from comic books. Similarly, if the book takes one artist as its main subject, it simultaneously touches on a wide range of figures—from Charles Dana Gibson and Robert Henri to Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol—while tracking the longer historical trajectory of illustration, including a section of the introduction, titled “What is Illustration?” that puts forth a list of the constitutive characteristics of illustrating as a modern visual form.

The process of researching and writing the book opened my eyes to the wide reach of illustration in contemporary culture. That’s true not just of a substantial portion of the twentieth-century image bank—cartoons and comic books, movie posters, all manner of print advertisements, political propaganda, et al.—but also of newer arrivals to the party, including computer-animated films and the sprawling, invented worlds of electronic video games. Illustration, defined as the creation of images that tell a story or deliver a message, lies at the heart of all these myriad cultural forms. While the dominance of modernist criticism throughout much of the last century meant that such products were often viewed with a skeptical eye by the cognoscenti (the influential critic Clement Greenberg famously railed against the destructive impact of what he called “kitsch,” a catchall category that included illustration), in our own time they have won acceptance in high culture. That is clear, for instance, in the recent embrace of the graphic novel as an accepted literary genre, as witnessed in the celebration of such important efforts as Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home. (Some would place such sequential art in a category apart from illustration, but I myself envision these types of graphic narratives, alongside comic books and comic strips, as a subset of the broader category of word-image combinations.) And, in our so-called post-medium age, illustration’s impact is evident as well in the contemporary visual arts (a development which no doubt would have dismayed Greenberg), with illustrative modes employed by such artists as William Kentridge, Kara Walker, and Robin Rhode.

This line of observation can be extended even further. A reasonable argument can be made that illustration is the lingua franca of our digital, networked culture, through specific forms of online and social media communication. Take the case of emoticons or emoji, those near-ubiquitous, emblemlike pictures that are used to convey emotional tone—surprise, sadness, a wink or grin, or what have you—in electronic messaging. Any time you add one of these to a text, instant message, or e-mail, you are doing a kind of illustrating; perhaps only in the simplest sense of that term, as a joining together of image and text for communicative purposes, but a form of illustration nonetheless. Similarly, one of the most common devices on websites like Reddit is the so-called image macro, comprised of a short (usually humorous) text added to a picture. These tend to feature characters plucked from pop culture (like Fry from Futurama or Captain Jean-Luc Picard from Star Trek: The Next Generation) or such memorable, user-generated characters as Success Kid, Overly Attached Girlfriend, and Bad Luck Brian. A website like Livememe, which allows you to add captions to these sorts of stock images, is basically an online illustration generator.

Obviously, the everyday user’s selection of emoticons and memelike image macros is far from the work of professional illustrators, who are trained to craft pictures for storytelling and messaging purposes, but the basic communicative functions are there nonetheless. As we recognize the widespread impact of this distinctive conjoining of pictures and words, the study of illustration—its history, its techniques, its major practitioners—grows ever more relevant.

* This essay was originally posted by Yale University Press on May 15, 2014.

May 29, 2014

Michael Lobel is professor of art history at Purchase College, State University of New York. In 2011 Dr. Lobel received a Rockwell Center Fellowship for senior scholars to assist his research toward the creation of this publication.