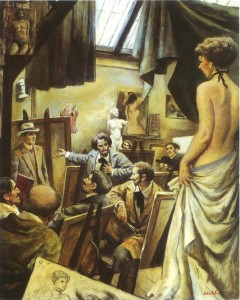

Ben Stahl (1910-1987)| The Grand Reflector, 1945| Illustration for “The Grand Reflector” by Phyllis Duganne in The Saturday Evening Post (November 17, 1945)

It’s the stereotypical art class in a studio that we all know. The students hold their paintbrushes and are dressed in their artist wear—similar jackets or smocks and loose, black ties. The female nude, with her back to the viewer, is elevated on a stand. Examples of artwork hang from the walls—from paintings to a nude statue. Peeking from the bottom is the top portion of an artist’s canvas—a frontal sketch of the nude that stands before the class.

This illustration by Ben Stahl (1910-1987) is for a story entitled, “The Grand Reflector,” by Phyllis Duganne published in the November 17th, 1945 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Stahl interest in art stemmed from his youth when he visited The Art Institute of Chicago with his grandmother. By the age of 17 Stahl worked as an apprentice at an art studio. Once working professionally, he began to illustrate stories for the Saturday Evening Post, eventually painting over 700 pictures for the magazine. Stahl is known for his more open and free form style. Rather than focusing on detail, he preferred the drama and emotion. As he said, he wanted his “paintings to excite the senses…I always try to get to the guts of a painting—to line and form.”

Duganne’s story, “The Grand Reflector,” set in 1912, tells of a nineteen year old American art student named Roger Thayer who travels to Paris to study art. In one scene, he decides to attend the Academie Julien, but upon entering the classroom he is heckled by the other students, who are all French. As they chant, “Chapeau! Chapeau! Chapeau!,” meaning “Hat! Hat! Hat!” in French, Roger runs out embarrassed and uncertain if he will return. This is the scene we see depicted in Stahl’s illustration.

Paintings of artists’ studios aren’t an invention of modern times. Even the ancient Egyptians and Greeks presented outsiders with views of artist’s private spaces—a view of their practice, belongings, and possible inspirations. Around the nineteenth century, paintings of artists’ studio became more commonplace in academic art. An example is Henri Fantin-Latour’s A Studio at Les Batignolles, in which some of the now famous impressionists—Renoir, Monet—and writer—Emile Zola—surround the leader of the movement, Manet. All hold directed and strong gazes and are dressed in clean-cut suits to express the gravity of their work.

In Stahl’s painting not only is there an already formed, cohesive group, as in Fantin-Latour’s painting A Studio at Les Batignolles, but there is also the new artist—Roger. He is pointed at, in a mocking manner and he is dressed differently. He wears a fedora and a three piece suit as he holds what seems to be a portfolio. The art students turn around to look—some with concerned faces, some with what seem to be smirks—as Roger enters.

What is interesting is that Stahl didn’t construct the illustration from Roger’s point of view, even though the story is told through Roger’s eyes. If the view was from Roger’s position, then we’d likely only see the backs of the art students’ heads as they worked on their drawings. We wouldn’t be able to see their expressions. Instead, Stahl places us in the perspective of the nude model. In this way, we are able to see the action-reaction of the scene—the action of the artists turning around and looking at Roger and the reaction that Roger has to the heckling. By choosing this view, Stahl focuses and heightens the drama and emotion of the scene and let’s the viewer see the embarrassment and agony on Roger’s face.

September 22, 2011

By Jessica Man, Post-graduate from Brown University and Curatorial Intern at the Norman Rockwell Museum, summer 2011