July 28, 2014 is the one hundredth anniversary * of the beginning of what the British called, The Great War. While America had already experienced the vast destruction (of humans and land) during our mid-19th century Civil War, World War I was the first time Europe experienced the broad devastation of land and people in the grinder of modern warfare. Not surprising, contemporary illustration reflected the conditions of the battlefields and trenches even as it sometimes reflected another sugar-coated version of the experiences of the common foot soldier.

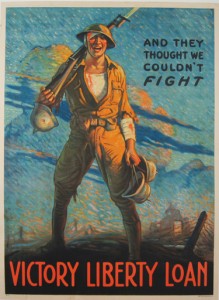

left, Clyde Forsythe (1885-1962); And they thought we couldn’t Fight: Victory Liberty Loan, 1918; Lithographic print on paper

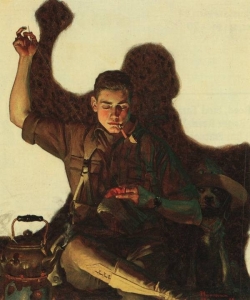

right, Norman Rockwell (1894-1978); If Only Mother Could See Me Now, 1918; Cover illustration for Life (June 13, 1918); oil on canvas; Private Collection

Clyde Forsythe (above) and hundreds of other American illustrators produced persuasive posters to aid the war effort. Goals for the posters were varied from the encouragement of the populace to do defense work, to recruitment, conservation of materials and food stuffs, and the ever present need to raise money to support the war like the Victory Liberty Loan poster seen above. Forsythe focused his poster on a young soldier, wounded, but jubilant with his prowess that includes the German helmet trophies he carries in his hands. To a populace who was used to seeing clean-cut young men in their pristine uniforms as in Norman Rockwell’s June 1918 Life magazine cover above right, illustrations like Forsythe’s must have been sobering. Even so, one observer at the Norman Rockwell Museum noted that the shadow cast in Rockwell’s illustration is reminiscent of a silhouette of a Hun about to attack the domestically focused soldier.

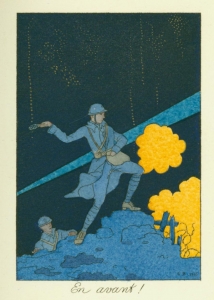

George Barbier (1882-1932); En avant!, 1916; Illustration for La guirlande des mois published 1917; Charles Rahn Fry Pochoir Collecton, Princeton University Library

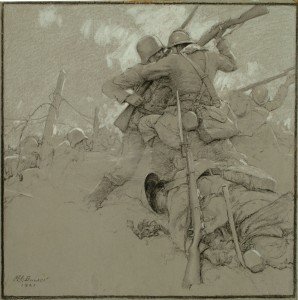

The French illustrator George Barbier’s above illustration of The Great War was published by Jules Meynial as part of a five-issue run of the annual La Guirlande des mois through 1921. Barbier’s war-time image was published in the 1917 issue. This rather simple image contains many of the elements that help to identify it as vintage WWI. For example notice the puttees that wrap a soldier from the knee to the ankle. They are long strips of woolen material, three inches wide, bound round and around the lower leg that were intended to stop water and mud sloshing into boots and onto breeches.** The flat-ish crown and narrow rim of an Allied soldier’s helmet is also distinctive to this period. And the bands of shoulder straps that hold various haversacks of the soldier’s kit, ammunition belts, and in this case a bag of grenades. Interestingly, Barbier illustrates the soldier almost as a young dandy—his uniform is still perfect and neat as he stands heroically atop a mound of barren earth about to throw a hand grenade. Another feature we find in many of the illustrations of The Great War are shattered fences and loose curls and lines of dangerous barbed wire damaged in battle that were meant to help protect each side’s trench system and mark opposing front-lines (see the detail of Barbier’s illustrations above). Story illustrations from after The Great War utilized many of the same elements to help to link the stories and their images to that war as you can see in the Maurice Bower illustration below. Delicately drawn in charcoal and chalk on gray paper, note the dead soldier in the foreground his discarded gas mask fallen beside him on the ground even as a soldier of the Allied forces fights hand to hand with a German soldier.

Maurice L. Bower (1889-1980); Festus had run away a coward, but he was brave enough all through that last night and day, 1917; Story illustration for “Idols” by Richard Washburn Child in Hearst’s International combined with Cosmopolitan (Aug. 1921); Charcoal and chalk on gray paper; Delaware Art Museum, gift of Jane and Benjamin Eisenstat, 1979-80

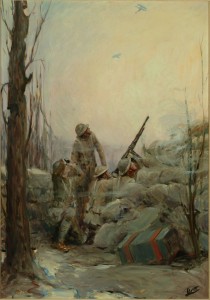

Harold Matthews Brett (1880-1955); Anti-aircraft machine gunner, n. d.; Oil on board; Delaware Art Museum, Louisa du Pont Copeland Memorial Fund, 1978-605

Another identifying aspect to illustrations about this time is the devastation of the war front landscape. Harold Brett’s illustration of an anti-aircraft gunner placed atop a stone wall or fence and pointed toward the sky posits a new view of war—machine against machine. Notice how even the hulk of the tree-trunk at the left of the painting exhibits evidence of the war with chunks bitten-out of its profile. The only living things seen in this illustration are the four soldiers clustered around the gun.

While it would be nice to visualize this and other wars with whole, hale, and hearty soldiers and landscapes, the very insistence of tougher, more realistic imagery, were meant to remind readers then and now that war is hell.***

* On July 28th, 1914, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia.

** Notice that Rockwell’s soldier wears canvas leggings over his trousers instead of puttees and that the his trousers were tapered below the knee and pulled snug with lacing to the ankle.

*** “You don’t know the horrible aspects of war. I’ve been through two wars and I know. I’ve seen cities and homes in ashes. I’ve seen thousands of men lying on the ground, their dead faces looking up at the skies. I tell you, war is Hell!” William Tecumseh Sherman’s address to the graduating class of the Michigan Military Academy (June 19, 1879).

July 24, 2014

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum