Camille Clifford: The ‘Gibson Girl’ Promise Fulfilled

by Skylar Smith, Fellow, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Rotary Photo, “Miss Camille Clifford,” London, UK.

Charles Dana Gibson (1867-1944) was one of the most prominent American illustrators at the turn of the century.[1] Much of his success was due to his creation of the “Gibson Girl.” As English Literature and Women’s Studies scholar Martha Patterson notes, his works focuses on women who are:

Tall, distant, elegant, and white, with a pert nose, voluminous upswept hair, corseted waist, and large bust. Charles Dana Gibson’s pen-and-ink drawing of the American girl, the Gibson Girl, offered a popular version of the New Woman that both sanctioned and undermined women’s desires for progressive sociopolitical change and personal freedom at the turn of the century.[2]

Patterson argues Gibson’s depictions walk the fine line of reflecting social patterns in a way that pushed gender norms forward by portraying women participating in unconventionally physical activities, like playing golf, riding bicycles, and swimming, but maintained decorum through each figure’s beauty and femininity.[3] The ‘Gibson Girl’ illustrations always followed the description aptly written by Patterson, but as F. Hopkinson Smith noted in his 1893 text, American Illustrators:

[Gibson] caught and fixed the true air and spirit of the ‘American Girl.’ Of course, he has not caught her in all of her protean variation. The action of different climates, the inter-mixture of different races, have made as many types of American girls as of chrysanthemums.[4]

Gibson created a recognizable type of woman, which, as Smith points out, allowed for variations. By offering multiple ideals, the ‘Gibson Girl’ aesthetic belonged to no one woman, yet offered the mantle to every woman. One lady who rose to Gibson’s challenge was the actress Camille Clifford (1885-1971), as evidenced by her postcards.

Clifford was a Belgian-born actress who lived in America briefly before settling in to a short-lived acting career in London, just after turn of the century. While in America, she won a magazine contest for being “the lady who should be… the most representative New York girl according to the famous Dana Gibson pattern.”[5] This victory earned her $2,000, and the acclaim it garnered, got her a non-speaking role as the ‘Gibson Girl’ in the Prince of Pilsen, a 1904 musical performed in London.[6] This initial theatrical success was followed by a larger role in The Belle of Mayfair, in which she had her own number, ‘I am a Duchess.’[7] According to a 1906 review in The Times: “The voice of Camille Clifford is not strong, but she wears such beautifully cut clothes and moves so elegantly up and down the stage that her turn is sure to be popular.”[8] Though not theatrically gifted in the traditional sense, Clifford was admired on and off the stage for her figure, clothes, and deportment—especially by her future husband and member of the peerage, Captain Henry Lyndhurst Bruce.[9] Following their engagement, Clifford announced her resignation from the stage, a decision she delayed until after their marriage when producers of The Belle of Mayfair offered her an additional song in the show, “Why Do They Call Me a Gibson Girl?”[10]

These postcards of Clifford primarily focus on her comeliness (figs 1-7). Little attention is given to the settings, though the use of uniform backdrops and interior furniture relate these photographs were taken inside a studio. In each photo, Clifford wears a dress with her hair up. In three of the images (figs. 2-4), she is sporting the same dark-colored dress: in one she is seated at an angle that further accentuates the extremeness of her hour-glass figure (fig. 2; the photo may have been manipulated to further heighten this illusion), and two where she is viewed from the side—angles that also showcase the fullness of her hips and bust in contrast to her small waist (fig. 3 and fig. 4). While she is attired in different clothing in the other photos, her silhouette remains an important feature. The few props present in these images portray Clifford as a feminine, fashionable, and sophisticated woman through their inclusion of flowers (figs. 3 and 5-7), stylish clothing (beautiful dresses (figs. 2-7), fur coat, hat, and muff (fig. 1)), and furniture commonly found within domestic spaces (figs. 1, 2, and 5). The only scene that alludes to her relationship with the theater is “The Masher’s Glance” (fig. 4). In this image, a caricature of an older gentleman with an exaggeratedly stiff collar, thinning hair, and monocle—presumably used to see her better—offers Miss Clifford a crown on a cushion. In response, Camille raises her chin in a refined, yet firm, refusal. This denial implies that she was not a lady to be bought and marked her as a respectable actress.[11]

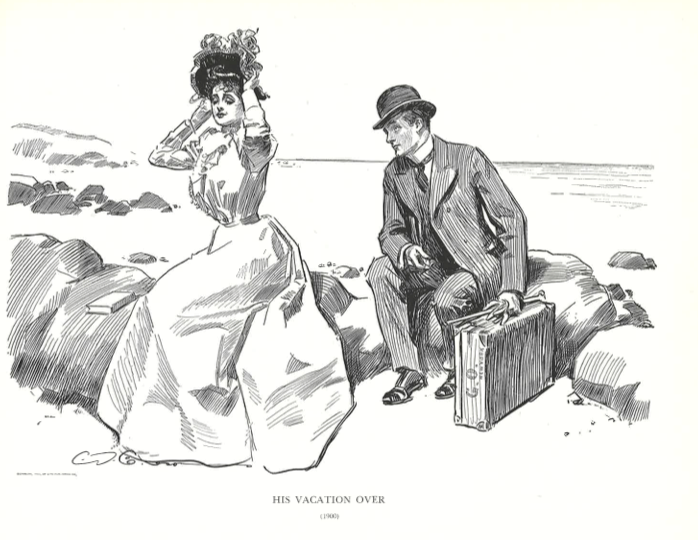

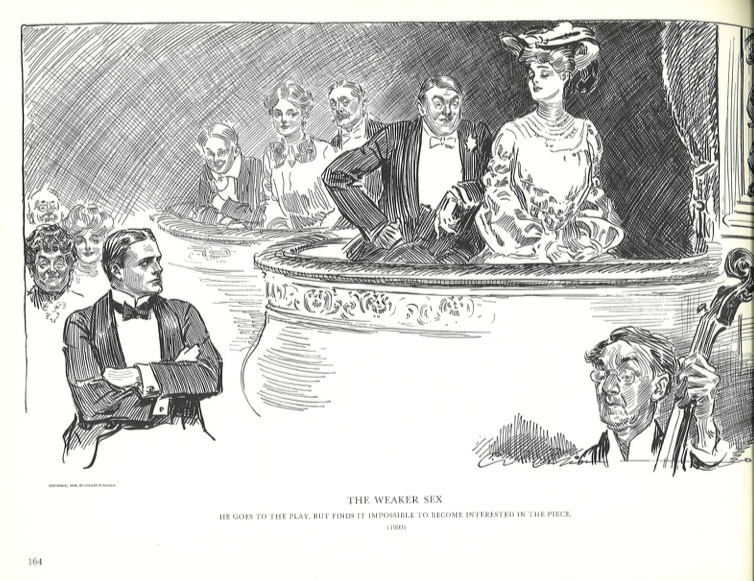

Given her exaggerated S-curve silhouette, the ratted hair piled carefully on her head, upturned nose, and style of dress, it is no wonder that Clifford was able to embody the “Gibson Girl”-type on stage.[12] Many poses for these English postcards pull directly from the illustrator’s works and similarities are easy to spot through comparisons with his sketches. Matching fig. 1 to fig. 8 allows viewers to see the similarities of expressions and styling of upswept hair tucked into a hat. Relating Fig. 2 to fig. 9 shows her mimicking of the ‘Gibson Girl’s’ regal posture when seated. Fig. 3 to fig. 10 notes the emphasis of, and similarity in, the facial features Clifford shared with the artist’s type. Fig. 4 to fig. 11 highlights the similarity of countenance when rejecting unwanted male attention. Matching fig. 5 to fig. 12 shows the proclivity for bared arms and shoulders with straight backs and lowered shoulders. Equating fig. 6 to fig. 13 calls attention to the high neckline, hairstyle, and loveliness of the face again while matching fig. 7 (middle image) to fig. 14, reveals the extreme forward angle that many of Gibson’s girls, as well as Clifford, adopted when walking. Strikingly, Clifford does not model any aspects of the sport culture in the postcards, which Gibson often depicted in his illustrations.[13] The actress did come from humble origins, however, claiming at one point to have lived on $7.50 a week during her run in Prince of Pilsen.[14] Given her ambitious marriage to Captain Bruce and her subsequent inheritance of the Baron Aberdale’s millions, her self-positioning toward the more refined end of Gibson’s collective works in these pictures could be a conscious decision made in the effort of elevating her class.[15]

Wanted by men young and old yet retaining the freedom to choose her own suitor, the ‘Gibson Girl’ was both attractive to and feared by men, and served as an inspirational figure for women in the US and western Europe.[16] Gibson documented and created a type of New Woman; the commercial success led to blatant consumerism, of images, and of objects that would help women fulfill their desire to be a ‘Gibson Girl.’ Patterson relates that: “Gibson Girl status… required a contractual obligation. Only by performing the identity the Gibson Girl image implied could one reap the rewards her image promised.”[17] Clifford was uniquely positioned to be like a ‘Gibson Girl’ given her beauty and figure, but she could also perform the role of ‘Gibson Girl’ to the point where she and her inspirational basis merged into one. Clifford’s acceptance and portrayal of this role is visible through her postcards and the dissemination of her dual role of actress and ‘Gibson Girl’ were made more personal through the act of writing notes on their versos and sending them to family members and friends.

Through her embodiment of this character, Camille Clifford was able to collect on the promise Gibson implies—that young, beautiful, and graceful women will meet and marry a handsome, wealthy, and gentlemanly ‘Gibson Man.’[18] Only at that point in her life did Clifford become the sportswoman who rode and raised racehorses. Though thousands of women endeavored to embody the postures, fashions, and styles of the ‘Gibson Girl’ in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Camille Clifford may have been the most successful one.

[crowdsignal rating=8860701]Figures:

Fig. 1 – Rotary Photo, “Miss Camille Clifford,” London, UK.

Fig. 2 – Rotary Photo, “Miss Camille Clifford,” London, UK.

Fig. 3 – Rotary Photo, “Miss Camille Clifford,” London, UK.

Fig. 4 – Rotary Photo, “Miss Camille Clifford – ‘The Masher’s Glance’ – ‘The Gibson Girl,’” London, UK.

Fig. 5 – Rotary Photo, “Miss Camille Clifford,” London, UK.

Fig. 6 – Rotary Photo, “Miss Camille Clifford,” London, UK.

Fig. 7 – Rotary Photo, “Miss Camille Clifford,” London, UK.

Fig. 8 – Charles Dana Gibson, “His Vacation Over,” 1900.

Fig. 9 – Charles Dana Gibson, “Un-named.”

Fig. 10 – Charles Dana Gibson, “Design for Wallpaper: Suitable for a Bachelor Apartment,” 1902.

Fig. 11 – Charles Dana Gibson, “The Weaker Sex: He Goes to the Play, But Finds it Impossible to Become Interested in the Piece,” 1903.

Fig. 12 – Charles Dana Gibson, “The Invincible Army,” 1900.

Fig. 13 – Charles Dana Gibson, “Unnamed,” 1903.

Fig. 14 – Charles Dana Gibson, “Accident to a Young Man with a Weak Heart,” 1900.

[1] Woody Gelman, The Best of Charles Dana Gibson (New York: Crown Publishers, 1969).

[2] Martha H. Patterson, “Selling the American New Woman as Gibson Girl,” Beyond the Gibson Girl: Reimagining the American New Woman, 1895-1915 (Indianapolis: University of Illinois Press, 2005).

[3] Ibid.

[4] R. Gary Land, “Charles Dana Gibson: Master Illustrator,” Illustration, Vol. 12 Issue 47, March 2015. 63.G

[5] “The Prince of Pilsen,” The Play Pictorial, July 1906. 144. Accessed Oct. 27, 2018. https://books.google.com/books?id=YVIZAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA3-PA144#v=onepage&q=camille%20clifford&f=false.

[6] Ibid. 144-45.

[7] Ibid.

[8] James Downs, “Camille Clifford (1885-1971), Gibson Girl – A Trio of Postcards,” Dark Lane Creative. Accessed Oct. 27, 2018. https://darklanecreative.com/camille-clifford-1885-1971-gibson-girl-a-trio-of-postcards-2/

[9] Clifford’s first husband, Capt. Bruce passed away in the First World War (1914). Clifford returned to the stage briefly before marrying Brigadier John Meredyth Jones Evans and retiring to the countryside once again. Terence Pepper, High Society: Photographs 1897-1914, (London: National Portrait Gallery, 1998).

[10]Downs, “Camille Clifford (1885-1971).”

[11] Actresses have a long history of being mistaken for, or actually participating in prostitution in American and European contexts both in reality, and through fictional portrayals, like Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie or Honoré Balzac’s Cousin Bette, for examples.

[12] All images of Camille Clifford are on the recto of English postcards. There are no dates listed on them and no specific theatrical connection is included, simply her name (with the exception of fig. 4). All are marked as “Rotary Photo,” meaning they were produced by the Rotary Photo Company of London and printed en masse using the rotary method of printing. “The Cabinet Card Gallery: Viewing History, Culture and Personalities Through Cabinet Card Images.” Accessed Oct. 27, 2018. https://cabinetcardgallery.com/category/rotary-photo.

[13]Though known for his cyclists and duffers, many of Gibson’s works did focus solely on the female figures (figs. 9, 10, and 13), much like the postcards of Clifford.

[14] “Gibson Walk and Fame Brings Fame and Riches to Obscure American Servant Girl Who Will Marry Heir to Peerage,” The Washington Times, Sept. 9, 1906.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Howard Chandler Christy who developed the “Christy Girl” as a variant and complement to the “Gibson Girl,” served as the first judge of the Miss America pageant. This honorary position reflects the important role illustrators had in shaping the ideals of beauty. Other judges include other famous illustrators such as James Flagg and Norman Rockwell. Susan E. Meyer, America’s Great Illustrators (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers, 1978). 242. Gibson’s illustrated images flourished, in part through Camille Clifford’s performances and postcards, but also through dances, fashion’s inspired by his figures, tableaux vivants where women could perform as ‘Gibson Girls,’ calendars, decorator plates, brooches, cigarette cases, and more. Gelman, The Best of Charles Dana Gibson, v-vii. Patterson, “Selling the American New Woman as Gibson Girl,” 33.

[17] Ibid. 44-45.

[18] The illustrator rarely depicted women after they are married, a practice further mirrored by Clifford, who retired from the stage after her nuptials and moved to the English countryside.

Bibliography:

“The Cabinet Card Gallery: Viewing History, Culture and Personalities Through Cabinet Card Images.” Accessed Oct. 27, 2018. https://cabinetcardgallery.com/category/rotary-photo.

“Gibson Walk and Fame Brings Fame and Riches to Obscure American Servant Girl Who Will Marry Heir to Peerage,” The Washington Times, Sept. 9, 1906.

“The Prince of Pilsen,” The Play Pictorial, July 1906. 144. Accessed Oct. 27, 2018.

https://books.google.com/books?id=YVIZAAAAYAAJ&pg=RA3-#v=onepage&q&f=false

Downs, James. “Camille Clifford (1885-1971), Gibson Girl – A Trio of Postcards.” Dark Lane Creative. Accessed Oct. 27, 2018. https://darklanecreative.com/camille-clifford-1885-1971-gibson-girl-a-trio-of-postcards-2/

Gelman, Woody. The Best of Charles Dana Gibson. New York: Crown Publishers. 1969.

Land, R. Gary. “Charles Dana Gibson: Master Illustrator.” Illustration Vol. 12 Issue 47, March 2015.

Meyer, Susan E. America’s Great Illustrators. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. Publishers. 1978.

Patterson, Martha H. “Selling the American New Woman as Gibson Girl” Beyond the Gibson Girl: Reimagining the American New Woman, 1895-1915. Indianapolis: University of Illinois Press. 2005.

Pepper, Terence. High Society: Photographs 1897-1914, London: National Portrait Gallery.Your Content Goes Here