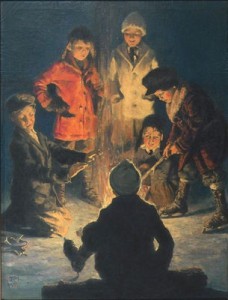

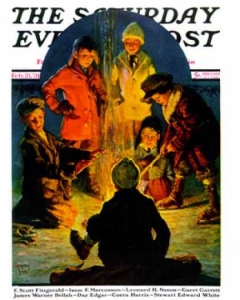

Eugene Iverd (1893-1936)|Campfire on Winter Lake, 1931 (aka, Skater’s Bonfire)|Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post (February 21, 1931)|Oil on canvas

This week we explore an illustration of a night scene with a group of boys bundled in their winter coats standing and sitting around a blazing campfire on a frozen lake. Painted by Eugene Iverd as the cover illustration for February 21, 1931 issue of The Saturday Evening Post, Curtis Publishing calls this cover image Skater’s Bonfire, although it is listed in a recently published biographical article on the artist as Campfire on Winter Lake.* True, a bonfire is an outdoor fire, but the connotation of a bonfire is that it is used for the disposal of burnable waste and that they have a tendency to be very large fires. A campfire, on the other hand, is a much smaller and more controlled fire whose purpose is to provide warmth or to be used to cook. Since the fire pictured here (more in the reflection of its light than a visually explicit fire) is small enough to be hidden behind the boy seated in the foreground, it seems to be that Iverd intended this to be a campfire.

By placing the boys as though they circle the campfire and putting the foreground seated boy so that his body shield’s our view of the fire, Iverd was making visual reference to the Caravaggisti, the 17th century stylistic followers of the 16th century Italian Baroque painter, Michelangelo Merisi da Cavaggio. One of their identifying characteristics is the use of strong light contrasted with deep shadows. Among the Caravaggisti, the French painter, Georges de La Tour was known for painting mostly religious scenes lit by candlelight; he is best known for the nocturnal light effects. By constructing his painting with the foreground woman shielding the light source, de La Tour helps us to focus our attention on the brightly lit newborn child sleeping in it’s mother’s arms.

Georges de La Tour (French, 1593-1652)|The Newborn, c. 1645|Oil on canvas|Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rennes, France

Iverd used the same trick of juxtaposing areas of light and dark to help us to focus on the boys gathered around the campfire. With the expressive comparison of the brightly illumined boys and the dark of the night surrounding them, we easily recognize the different sizes and possible age differences among them. Each boy is distinctively dressed and posed. The fire-light reflected in their faces shows us varying levels of intensity, cheer, or response to the heat and cinders produced by the fire. Most interesting of all is Iverd’s positioning of the boys in this scene. From foreground to background the boys increase in relative size and possible age. This is a reverse of normal perspective construction: with the larger figures in the foreground and the smaller further away in the picture plane. Iverd intended, I imagine, to help to draw the viewer in as though a participant poised behind the seated boy in the foreground.

The comparison between Iverd’s painting and the published Post cover is also interesting. In the published version the night sky is cropped to create a circular edge encircling the boys standing in the background of the picture. This reflects the Post’s sometime use of a circular form or field as a standard design feature in their covers, just like the black line delineating the space that contains the magazine’s date and price.

Eugene Iverd was the pseudonym of the painter George Erickson, a Minnesota native who trained as an artist at the St. Paul School of Art and then at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. After discharge from service in the U. S. Army, Erickson settled in Erie, Pennsylvania to work in a public school as an art teacher. In 1926 he submitted four canvases to The Saturday Evening Post, his first was published in March 13, 1926. ** As you can see in his illustration work, and in his other cover illustrations for the Saturday Evening Post, Iverd was primarily an illustrator of children’s scenes.

* See “Eugene Iverd: American Illustrator for The Saturday Evening Post” by Dr. Donald Stoltz, Jean Sakumura, and Lynda J. Farquhar in Illustration Magazine v.1, # 3 (reissued Summer 2009): 81.

** Between 1926 and his death in 1936, Iverd produced 29 cover illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post.

October 21, 2010

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum