Robots are now a real part of our world: automobiles are constructed at least in part by robotic devices; home-focused robotic devices vacuum our carpets and clean our floors; and other robots are being developed to make our lives easier. So, where and when did the idea of robots become a part of our culture and one of our cultural goals for the future? And how have their looks changed over the years?

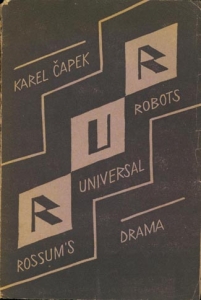

In 1920 the Czech writer Karel Čapek (January 9, 1890-1938) wrote a play, R. U. R., about a factory that makes artificial people–“robots.”* Close to humans in look and sound, these robots think for themselves. While they seem happy to work for humans, eventually they foment rebellion that leads to the extinction of the human race. R. U. R. are the initials of the company, Rossum’s Universal Robots.

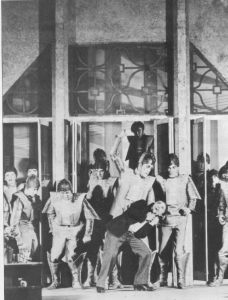

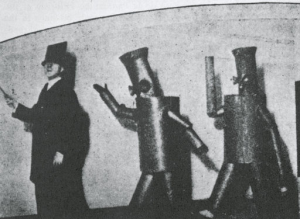

The cover of R. U. R.’s first Photo of scene from the play showing robots in

publication in 1920. rebellion from 1922 production.

The photos that show an early production of the play reveal robots that owe some of their look to concepts of futuristic reality and even to futurism’s (and cubism’s) interest in movement and mechanics.** It is interesting that one of the futurists, Fortunato Depero, also designed costumes for his 1924 ballet, Machine of 3000, with some of the characters being robots (see below).

Fortunato Depero ( 1892-1960) Fortunato Depero ( 1892-1960)

Designed costumes for his ballet Machine of 3000, 1924 Motociclista, 1944

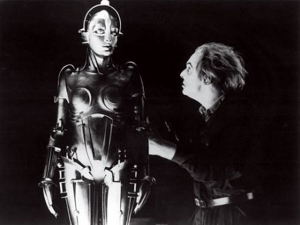

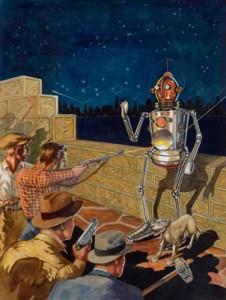

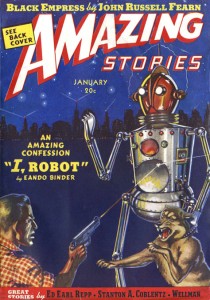

Fritz Lang (1890-1976) Robert Fuqua (1905-1959)

Maria and Rotwang I Robot, 1938

Photo still from Metropolis, 1927 Cover illustration for Amazing Stories (January 1939)

Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis showcased the robot Maria, created by the scientist/inventor Rotwang as a machine-human meant to replace the more fallible humans. In the 1930s and 40s mechanical men were often characters in serialized movies like Superman, Flash Gordon or Buck Rogers. By 1939 the brothers Earl Andrew Binder and Otto Binder published their heroic robot story, I Robot, about the robot Adam Lind under their pseudonym Eando Binder in Amazing Stories (see above). The cover illustration by Joseph Wirt Tillotson (a.k.a., Robert Fuqua) depicts a metallic construct that had already become the norm for imagining how robots look.

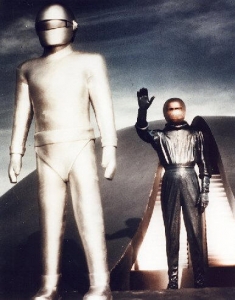

Isaac Asimov’s first robot story “Strange Playfellow,” published in the September 1940 issue of Super Science Stories, was about a robot Robbie designed to care for children.*** Asimov’s later story I, Robot, was published in 1950, with the story’s title chosen against the author’s wishes. The 1956 MGM science fiction film Forbidden Planet featured the character Robby the Robot, an expensive film prop that was used again in another film and on various episodes of The Twilight Zone. Robby appears to have been made of various mechanical parts only with a bit of a mid-century biomorphic twist in his look. Another mechanical robot constructed with soft curves was Gort from The Day the Earth Stood Still from 1951. Its humanoid seamless appearing robot, Gort did not speak, but used his beam weapon to vaporize obstacles even as his human counterpart Klaatu urged earth’s governments to commit to peace. Gort appears to have been constructed of a flexible metallic material.

Buddy Gillespie (1899-1978) and Addison Hehr

Mentor Huebner (1917-2001) Gort and Klaatu, 1951

Robby the Robot, 1956 For The Day the Earth Stood Still

For Forbidden Planet

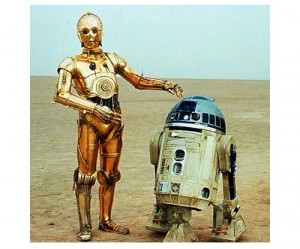

The 1977 space epic Star Wars offered a plethora of robot characters and robotoid forms, interestingly the characters C3P0 and R2D2 were once again stiff metallic figures. When Douglas Adams’ 1978 radio drama The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy came to the small screen, the robot character, Marvin the Paranoid Android (voiced by actor Alan Rickman on the television series) was made of softer rounded metallic forms with an over-sized head.

C3P0 and R2D2 Marvin, the Paranoid Android

From Star Wars, 1977 From Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, 1981

What began this wander through images of robots was curiosity of where the form came from, and what or who was the foundation for future forms and images. Off the top of my head I expect that it was William Wallace Denslow’s image of the Tin Woodsman character Nick Chopper, created for L. Frank Baum‘s 1900 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz story, that was probably one of the earliest images of a figure constructed of metal parts. The notion for this character is said to have been inspired by a figure made of metal pieces and parts Baum constructed for a shop display when he was editing a magazine on decorating shop windows to earn a living while he wrote the first Oz book. In the story the tinsmith Ku-Klip replaced Chopper’s living appendages with metal replacements as they were chopped off by his enchanted axe.

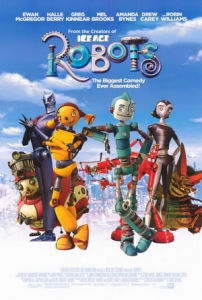

William Wallace Denslow (1856-1915) Robots, 2005

Nick Chopper, the Tin Woodsman Poster for Blue Sky Studios and Twentieth Century Fox

Story illustration for The Wonderful Wizard production

of Oz by L. Frank Baum (Chicago, New York:

George M. Hill Co., 1900)

To take the model of the robot made of parts and pieces full circle, we need only reference the constructed characters of the Blue Sky Studios 2005 animated movie, Robots. In this story the characters of the low-end districts are composed of various parts and pieces and even refuse while the residents of the High-End district are comprised of sleek shiny new metallic parts. For example the wrapped wire pig-tails Fender’s sister, Piper Pinwheeler sports end in shower heads and Fender’s head is in part pieces of a press coffee pot. The movie’s central character, Rodney Copperbottom, is born after his parents construct him during ‘labor’ from the parts provided in a box.

Robots are a modern-world concept and image, that have become part and parcel of our lives. Thank you Karel Čapek, born on January 9, 1890.

* The robots that R.U. R. manufactures are really cyborgs or clones.

** For example, Fortunato Depero’s painting of a moving motorcycle ridden by a robot from 1944, seen above, (based on his cyclist images of the 1920s) is reminiscent of Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space from 1913.

*** Asimov’s story was written in May 1939 and he initially titled it “Robbie.” The cover of the September 1940 Super Science Stories makes no mention of Asimov or the robot story.

January 9, 2014

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum