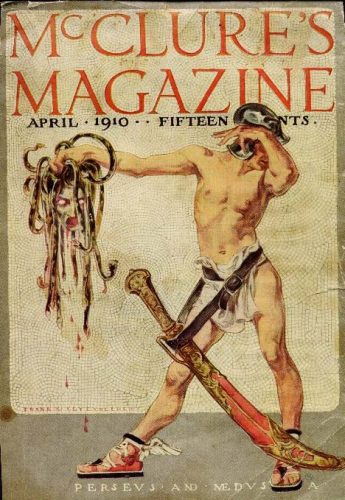

Frank X. Leyendecker (1878-1924)|Perseus and Medusa|Cover illustration for McClure’s Magazine (April 1910)

Although not as well known as his older brother J. C. (Joe) Leyendecker, Frank X. Leyendecker was also an illustrator of great skill.

For this cover of McClure’s, Leyendecker illustrated the myth of Perseus and Medusa. As the story is told in the Metamorphosis, guided by Hermes and Athena, Perseus went to the nymphs who had in their possession winged sandals and the kibisis, a magic sack, or safekeeping. They also had the helmet of Hades. Gathering the magical items, he flung on the magic sack like cape, tied the sandals on his feet, and placed the helmet on his head. Wearing the helmet, Perseus could see whomever he cared to look at, but was invisible to others. He also received from Hermes a curved blade made of adamant, a stone of extreme harness and incapable of being broken.

Perseus then sought the Gorgons, three dreadful female creatures whose hair was composed of venomous snakes and whose gaze turned to stone all who upon them. Of the three only Medusa was mortal. It was her head that Perseus set out to retrieve. Perseus looked only at Medusa’s reflection in his bronze shield as he beheaded her. He then placed the head in the bag and returned with his prize.

Leyendecker’s cover illustration of Perseus with the head of Medusa might also have been suited to a New Year’s cover because the accounting of this time frame tends to inherently be concerned with transformations. In light of Leyendecker’s classical art education, he used all the requisite items to detail his image: the winged sandals, the helmet of Hades, and an extremely large sword hanging from a belt over his loin-cloth covered hips. Perseus is not coughing into his elbow, but because he is without his polished shield, he covers his eyes with his left forearm while he holds the horrific head of Medusa in his right hand. Most remarkable is the extreme size of the adamantine blade. We might ponder the blatant sexuality of the placement and size of the sword, but one can only speculate regarding Frank Leyendecker’s implied tease.

Compare Leyendecker’s rendition of Perseus and Medusa with one created in 1902 by the illustrator Bertha Corson Day, as seen below. While both deliver the classical story with all its details, Day’s is rather cooler than Leyendecker’s. His seems much more expressive, emotional, and definitely more responsive to the gore of the story. Like Caravaggio’s 16th century Medusa painted on a shield, Leyendecker’s snakes seem to still be alive enough to continue to writhe and wiggle.

The real tour-de-force of the Leyendecker image is the white background constructed so as to appear to be a wall of white tesserae mosaic. The blood dripping from the severed Medusa’s head in this work is set off against the white of the mosaic, as are the red mouth and the red rimmed eyes of the creature. Not only did Frank Leyendecker used this same mosaic background device in another illustration, so too did his brother Joe in his earlier 1900 advertisements for Ivory Soap, see an example below.

Endings and beginnings are inevitably intertwined. So, with the Gorgon’s head accounted for, I now bid you all a happy new year to follow.

Bertha Corson Day (1875-1968)|Headpiece for “Perseus,” 1902|Illustration for Where the Wind Blows by Katharine Pyle (New York: R.H. Russell, 1902)|ink and gouache on board|Delaware Art Museum, gift of Mrs. J. Marshall Cole, 1988-164

Caravaggio (1573-1610)|Medusa, 1597|Oil on canvas, mounted on wood|The Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy

December 31, 2009

December 31, 2009

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum