Hats keep you warm, provide cooling shade, are revealing, concealing, and sometimes purely decorative. A hat usually provides the finishing touch to a person’s dress, complementing an ensemble and unifying the appearance. Whatever their purpose, a hat reveals something about its wearer: their sense of style, purpose, activity, or class.

Illustrations that include hats allow us to use them as hieroglyphs—as a readable symbol demonstrating a person’s relationship to the larger world.* When viewed as a trope, a hat may describe the relationship between the self and the world and may be considered a metaphor of the class and social status of the individual under its brim. In the 19th and early 20th centuries illustrators sometimes used specific types of hats to assist readers in constructing the meaning of their subject.

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)

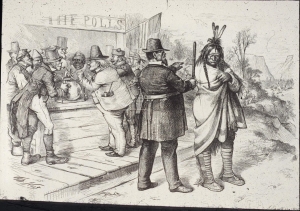

“Move On!” Has the Native American no rights that the naturalized American is bound to respect?

Political cartoon for Harper’s Weekly v. 15 no. 747 (April 22, 1871): p. 361.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

When illustrators like Thomas Nast or Winslow Homer used a specific type of hat on specific characters in their published cartoons or illustrations, they would have expected the people looking at their images to understand their visual cultural allusions. Moreover, contemporary people would have understood hat styles commonly used in their own time, much as we might understand a family’s class by the neighborhood they live in or from the cars they drive.**

Hats were sometimes used in 19th century illustrations as a signifier of cultural or racial types. For example, Thomas Nast used a combination of hat types, clothing with accoutrements, and facial physiognomy to indicate the origins of a variety of American immigrants. In his Harper’s Weekly political cartoon Move On, (see above) the hats, costumes, and faces pictured define the cultural origin of the men illustrated. While a number of Nast’s characters wear some version of a stovepipe hat, at the right of the groups in the background is a man wearing knickers and a Tam o’ Shanter, a hat traditionally worn by a Scotts man. To the Scottish man’s proper left is a German or Swiss man with a long pipe in his coat pocket—on his head he wears a version of a Tyrolean hat, a Homburg-like felt hat (in this case with the crown undented) decorated with a corded band and a feather ornament. Nast delineated the feather just above the ear of the gentleman from the Alpine region of Europe. To the far left of the same group is a Frenchman with his exaggerated mustache, obvious goatee, who wears a well-worn French military hat called a Kepi–identified as having a flat circular top and a visor. And almost lost in the background is a round-faced man who looks like he has a pointed head. That may be Nast’s nod to the Oriental population who wore conical straw hats called a Coolie hat. The very variety of people accepted and gathered at the election polling place in Nast’s cartoon makes the plight of the Native American even more unjust.

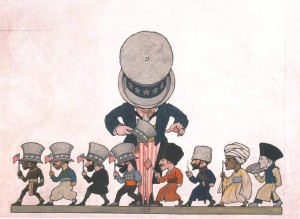

Thomas Guernsey Moore (1874-1925)

Uncle Sam, 1921

Illustration for “The Comedy of Americanization” by Katharine Fullerton Gerould in The Saturday Evening Post v. 194 # 18 (October 29, 1921)

Gouache on academy board

Kelly Collection of American Illustration Art

This notion of a hat being an identifier of racial, social, and cultural identification is turned on its head in Guernsey Moore’s 1921 above illustration called, Uncle Sam. Moore’s illustration show’s an Uncle Sam figure replacing the native hat of each of the smaller figures that move past him in the foreground. By removing each figure’s own culturally distinctive hat or head covering and replacing it with an Uncle Sam hat and an American flag, the homogenized Americanization of immigrants and/or new citizens would appear in Guernsey’s eyes to be complete.

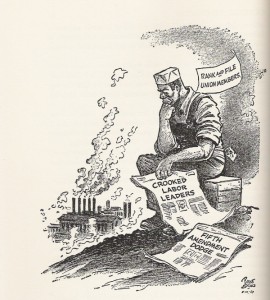

Thomas Nast (1840-1902) Bruce Shanks (1908-1980)

Labor Cap The Thinker, 1957

Illustration study for Harper’s Weekly (February 7, 1874) Political cartoon for The Buffalo (Evening)

Ink on tracing paper on paper News published August 1957

Library of Congress, Cabinet of American Illustration,

CAI – Nast, no. 36a (A size)

Bruce Shanks created the above political cartoon in the summer of 1957 in response to an investigation of the AFL’s (American Federation of Labor) Brotherhood of Teamsters by the U. S. Senate Labor Rackets Committee. The teamsters union members are represented by a seated laborer in his coveralls, posed like Rodin’s easily-recognized statue, The Thinker. The worker’s shirt sleeves are rolled up revealing his large muscled arms and on his head is a typical factory worker’s hat—a box-like form made from folded paper. Because it was disposable, it had long been the perfect hat to wear in a dirty factory and one that was reconstructed freshly each day—as we can see in Thomas Nast’s sketch of a similar hat from nearly three quarters of a century before Shank’s cartoon. A union member seeing Shank’s cartoon would recognize his seated figure as another factory laborer by this distinctive hat, as opposed to a man pictured in the same outfit but wearing a straw hat who would have been recognized as a farmer.

As you can see, hats (in addition to clothing) were often used by illustrators to designate certain national or cultural types. Hats were employed to establish a character’s social status, political leanings, and life prospects. Hats were often also used as a wordless subtext of an illustration depending upon the viewer’s acuity and social knowledge to unveil their meaning.

* The realization of the possibility of a hat as an analytic tool occurred many years ago when looking at a reproduction of Edouard Manet’s, Dejeuner sur l’herbe, 1863; Collection of the Musée d’Orsay, Paris. In that painting, the clothing of the semi-recumbent gentleman on the right indicates to me that he is an artist as he wears a painter’s chapeau and a lush floppy bow tie under his shirt’s collar. I would like to thank a colleague, Phil Archer at Reynolda House Museum of American Art, for seeding this study with the loan of the book Kafka’s Clothes by Mark M. Anderson (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992, 1994).

** Using cars as a method of typing class or social order today is not so easy. The car one drives might better represent one’s aspirations than one’s economic class because of our ability to finance or lease our automobiles.

March 6, 2014

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum