James Montgomery Flagg (1877-1960)|I Want YOU for U. S. Army, c. 1917 and I Want You, February 1917|Poster, lithographic print and photomechanical print|Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C., POS-US.F63, no. 9 (C size) and AP2.L52 Case Y

When World War I erupted, James Montgomery Flagg was already a well known artist. Beyond the age for military recruitment, he fulfilled his nationalistic duty by creating patriotic posters for the war effort. This famous image created by Flagg encouraged recruitment for the United States Army. The original watercolor of Uncle Sam created by Flagg first appeared on the July fourth cover of Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly Newspaper in 1916 and then in poster form. Uncle Sam was represented as a stern elderly gentleman dressed in a blue blazer and red bow tie wearing a top hat decorated with stars on a blue background. He has an air of authority as he points his finger directly toward the viewer with the caption “I want YOU for the U.S. Army”. Flagg was the first artist to present Uncle Sam with this “take charge” gesture transforming him from a passive elderly man into an authoritative respected leader. Using a simple design and a strong message over four million copies of this poster were printed during World War I and the poster was reenlisted during World War II.*

The emergence of Uncle Sam as a patriotic American symbol occurred more than a hundred years prior to World War I. During the first quarter of the nineteenth century, a period when the new American Republic was reasserting its rights and establishing an identity, the young country had no hereditary monarch nor were they anxious to acquire another powerful parent.** The idea of an uncle as the symbol for the country was indicative of the American attitude toward the government of the young republic. Uncle Sam presented as an amiable elderly gentleman became the patriotic symbol for the American nation.

The Uncle Sam character was derived from an actual person named Samuel Wilson born in Arlington, Massachusetts in 1766. After the Revolutionary War, Sam and his brother, Ebenezer, relocated to Troy New York and established a profitable meat packing company. During the War of 1812, Sam was granted a government contract to supply meat to the American troops. He was also assigned the duty of Meat Inspector for the Army. After inspection, he stamped the crates of beef “U.S.” an abbreviation for United States. However, during the early 1800’s, the common abbreviation for the United States was “U. States” and Samuel’s stamp created confusion. Samuel Wilson was an amiable man and known by his nieces, nephews and neighbors as Uncle Sam. Consequently the American soldiers interpreted the “U.S.” stamp as provisions from Uncle Sam and began referring themselves as Uncle Sam’s soldiers. ***

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)|Cur-Tail-Phobia about Civil Service Reform|Cover illustration for Harper’s Weekly (April 22, 1876)

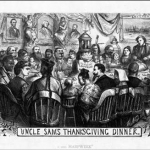

By the 1820’s, Uncle Sam was growing in usage as a term referring to the United States, but the image of Uncle Sam was established much later. Political cartoonist Thomas Nast helped determine the original image of Uncle Sam after the Civil War. Nast’s first image of Uncle Sam appeared in the November 20, 1869 issue of Harper’s Weekly. The illustration titled Uncle Sam’s Thanksgiving Dinner presents Uncle Sam as a symbol of unity and equality. He welcomes American’s of all nationalities and gender to dine together at his Thanksgiving feast. In the November 24, 1876 issue of Harper’s Weekly, Nast’s image of Uncle Sam evolved as an affable elderly gentleman wearing his recognizable tailored coat, striped pants and a decorated top hat.

Although James Montgomery Flagg achieved fame from his Uncle Sam war posters, the patriotic posters represent only one aspect of his artistic versatility. After World War I, nearly every major magazine featured Flagg’s art work. He regularly contributed to publications including Judge, Life, Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, Scribner’s and many others. Flagg displayed his ability with pen and ink, water color, charcoal and pencil and oils. He also preferred using live models idealizing all that was beautiful. The Flagg girl was tall and shapely with thick wavy hair and feminine allure. His young men were depicted as attractive and masculine with charm. Flagg frequently used himself and his wife as models for his illustrations. While many of Flagg’s contemporaries such as Norman Rockwell and N. C. Wyeth idealized small town America or dramatized the American West, Flagg preferred to illustrate the world in which he lived. Born and raised in New York City, his illustrations captured American urban and political life of the early twentieth century.

* Susan E. Meyer, James Montgomery Flagg (New York: Watson-Guptill Publications, 1974): 37. About 4 million copies of this poster were estimated to have been issued during the first World War and about 400,000 in the second.

** Elinor Lander Horowitz, The Bird, the Banner, and Uncle Sam (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1976): 34.

*** Alton Ketchum, Uncle Sam The Man and the Legend (New York: Hill and Wang, 1959): 40.

July 1, 2010

By Colleen Boyle, for the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum