In the early part of the 20th century, American artists looked to contemporary music as a viable exemplar of time and motion to apply to their visual expression giving the more static traditional forms of painting and sculpture a new energy and a sense of movement. Ragtime, the Blues, and Jazz provided new snappier or soulful tunes that compelled artists in Europe and America to seek their own versions of those idioms in their work.

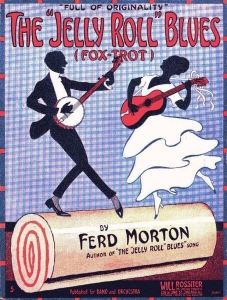

One source of imagery that might have influenced artists could be found on the illustrated covers of sheet music. An early example is the cover for the piano sheet music (see below) of Ferd (Ferdinand) Morton’s The “Jelly Roll” Blues published by Will Rossiter in 1915. On the left, this early unattributed sheet music illustration depicts a couple of black musicians—a man playing a banjo and a woman playing a guitar–while

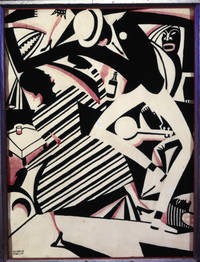

dancing atop a jelly roll cake against a blue and white check background.* The rolled dance ‘floor’ provides no stable purchase for the musicians, but then the music is not too stable either—it is typically edgy with polyrhythms and syncopated improvisation. Within a few years, artists like the German-born Winold Reiss (seen above), took the beat of the music and visualized it into an off-kilter (and difficult to read)** image of the sound and the loose movement of the dance it inspired. The Dean of the Harlem Renaissance, philosopher and educator Alain Locke described Reiss’s artistic process as a, “. . . folk-lorist of brush and palette seeking always the folk character back of the individual, the psychology behind the physiognomy. In design, he looks not merely for the decorative elements, but for the pattern of the culture from which it sprang . . . .”***

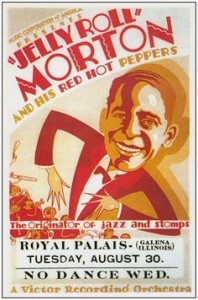

Unknown artist; Advertising poster for “Jelly Roll” Morton and His Red Hot Peppers, 1927; For performance at the Royal Palais Ballroom in Galena, Illinois

A couple of years later a promotional poster for “Jelly Roll” Morton and His Red Hot Peppers and a night’s performance in Galena, Illinois, reveals the adaptation of Winold Reiss’s jazzy dance imagery in a piece of ephemeral art. In this poster the image of Ferd Morton and the echoing syncopation of the music merge into resonating areas of color shadowing the musician’s body. The head is portrayed more realistically and proportionately larger than the performer’s body, that is tilted and dances along with the implied music.

Like the Americans, the French were captivated by jazz music. In 1925 an American company of 20+ black performers, the Revue Nègre, arrived in Paris. The troupe included jazz soloist Sidney Bechet, and a chorus with eight dancers—among them Josephine Baker. This American group combined a jazz band, original choreography, burlesque pieces, and movable scenery. The performances offered exquisite lithe semi-nude bodies without vulgarity. The revue offered Parisians a glimpse of authentic “black culture” removed from the colonial experience, wrapped within a modernist artistic expression.

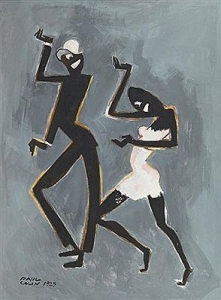

French artist and illustrator Paul Colin’s initial poster for the Revue (shown below) illustrates two black men, most likely musicians or performers, and one black woman dancer partially clothed in a slip-like garment. In this early illustration of the troupe less attention is paid to the musicality of the group or their focus on jazz than on the relative blackness of the three performers portrayed—the men are not only darker-skinned, but their lips are exaggerated in size and color. The caricature aspect of this poster seems influenced by the work of Miguel Covarrubias. The lighter skin-tone of the woman dancer suggests that this figure references Josephine Baker.

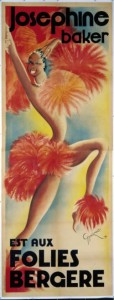

Following the initial poster, Paul Colin painted and illustrated a variety of images of the black dancers in the troupe. Like Winold Reiss’s image of jazz and the jazzy poster image of Morton, Colin’s images of jazz dancers employ the rhythmic angularity of arm movement and cocked knees moving in the opposite direction of cocked hips to represent the edgy polyrhythmic, syncopated improvisation of jazz and may also reference the Charleston—the dance Baker introduced to Paris.**** Josephine Baker commented on the dance, ”For too long people have hidden their behinds: they exist, I see no reason to be ashamed of them.”***** Contrast Colin’s middle painting above with Michel Gyarmathy’s slightly later poster advertising Baker’s performance at the Folies Bergere. Gyarmathy’s vision of Josephine Baker reveals a considerable expanse of her light-skinned blackness accentuated by the large and small orange pompoms that both reveal and conceal her sinuous body. As you can see, jazz music and its related dance were an important aspect of the opening up modern visual culture reflecting certain aspects of life in the early 20th century.

* A jelly roll cake, also known as a Swiss Cake, is made in one thin layer. After it’s removed from the baking pan, it is covered with jam or buttercream and the layer is rolled into a log-shaped cake. FYI, the term jelly roll can also refer to both female genitalia and to the act of intercourse.

** A dapper gentleman dances wearing a black jacket and white sacks. He has a white boutonniere in his dark jacket lapel and wears a white boater hate with a black hat band on his head. His right arm is lifted up and his left arm echoes the movement but it pointed downward. Similarly his right leg is lifted up and the left leg is down. His body fills the upper and right side of the image. Correspondingly the woman he dances with fills the middle and left side but does not fill the lower edge of the work, except for her right foot that stands on the white floor at the lower edge of the work. Notice that her feet appear to cast shadows in the bright light. She is more difficult to see because her horizontal striped dress reads as an undifferentiated area. Her hands are marked by reddish pink fillips—the right may be seen on the body of the dress and the left hand extends from the black and white stripe to touch the gentleman’s body. The back of her head shows the same reddish pink tone, as do her lips. Filling up the rest of the space are a night club table, an African mask, shapes that look like leaves, and at the lower right an accordion pleated shape that might be a camera with the bellows open.

*** Alain Locke, Survey Graphic. V. 53 (March 1, 1925): page 653.

**** In 1927 Paul Colin published a portfolio of his drawings of Josephine Baker and the Revue Nègre performers titled Le Tumulte Noir (The Black Craze).

*****See https://www.npg.si.edu/exh/noir/broch3.htm

June 26, 2014

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum