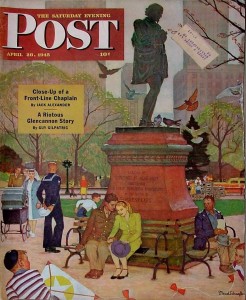

Mead Schaeffer (1898-1980) | Romance Under Shakespeare’s Statue | Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post (April 28, 1945)

William Shakespeare, Sonnet 55

Not marble, nor the gilded monuments

Of princes, shall outlive this powerful rhyme;

But you shall shine more bright in these contents

Than unswept stone besmear’d with sluttish time.

Between 1942 and 1944, Mead Schaeffer created fifteen cover illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post picturing various aspects of the U. S. armed forces. To develop these covers, Schaeffer worked as a war correspondent for The Post visiting all sorts of units, for example riding with submariners and on various aircraft so that his images authentically recreated the men’s life of service. The original paintings for these covers travelled throughout the United States and helped to raise money for war bonds. By the end of November 1944, Schaeffer’s Post covers turned to depicting life at home.

When wasteful war shall statues overturn,

And broils root out the work of masonry,

Nor Mars his sword nor war’s quick fire shall burn

The living record of your memory.

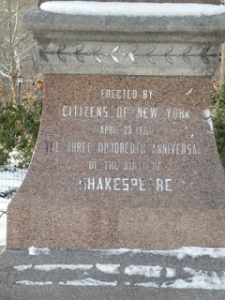

For the spring scene seen here, Schaeffer chose to focus the action in New York’s Central Park, at the base of John Quincy Adams Wards’ William Shakespeare Statue, completed in 1872, and located on The Mall near East 66th Street. The impetus for the creation of this public monument was the 300th anniversary of Shakespeare’s birth in 1864 when a group of actors and theatre managers received permission from the Park’s Board of Commissioners to place a statue of the playwright in the park. Ward was selected as the sculptor in 1866 and money was raised by various benefits and performances.

‘Gainst death and all-oblivious enmity

Shall you pace forth; your praise shall still find room

Even in the eyes of all posterity

That wear this world out to the ending doom.

In this illustration around the base of Shakespeare pigeons flock to rest at the great man’s feet and a variety of couples enjoy each other amid the burgeoning greening of nature. While there are some individuals depicted in this scene, it is mostly about men and women coupling: the obvious pair, a soldier and his sweetheart seated at the foot of the statue; a nurse* pushing a baby carriage being admired by a slim sailor; and behind the nurse another military man walks with his girl. Other couplings include the boy and girl in the extreme foreground running with a kite; a woman walking her dog near the traffic light; and another boy and girl purchasing something from a food vendor near the street. Despite the horror and loss of war, what is hopeful is that love still blooms and each of us seeks our mate.

The central couple sit on a park bench placed against the base of the statue’s pedestal in front of the monument’s inscription: “Erected by · Citizens of New York · April 23, 1872 · The Three Hundredth Anniversary · of the Birth of · Shakespeare.” What I find interesting is that either Mead Schaeffer or the art editor of The Post chose to color the pedestal in brighter tones than it really is. Instead of being cut from a bright red stone with a green stone trim, the actual pedestal was cut from red and grey colored granite whose colors are much more muted. (see below) For the Post cover version, we might interpret the green tone as being a mold, but if it were mold then the rest of the pedestal would be green tinted as well.

But most remarkable to me is that while Mead Schaeffer clearly painted the glint of sunlight on the great man’s figure and along the edges of the pedestal, neither statue or monument (or people in the scene) cast a shadow. Perhaps Schaeffer’s lapse was not a lapse at all, but instead a reference to Shakespeare’s notion that love indeed shines brighter and lasts longer than anything else.

So, till the judgment that yourself arise,

You live in this, and dwell in lover’s eyes.

* The nurse’s wimple-like head covering reminds us that the nursing profession was begun by early nuns and so some of the nurse’s uniform was at one time reminiscent of a nun’s habit.

August 23, 2012

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator,Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum