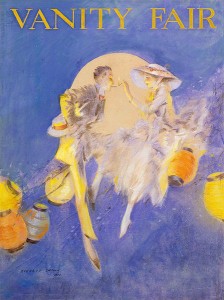

In 1916 the illustrator Everett Shinn was commissioned to create the first of June cover illustration for Vanity Fair magazine (see below). To express the frothy entertainments of summer, Shinn portrayed an upscale dandy with his boater in his proper right hand and his elegantly dressed companion seated among or straddling the bough’s of a tree, poised against a rising moon. The faces of the couple dressed in their pale-toned summer clothing reflect the yellow flame of a lit match she holds to light his cigar/cigarette. The backsides of their clothing also reflect yellow light, this time cast by the Japanese paper lanterns hanging from the tree’s branches. The message is clear: summer equals beautiful slim people enjoying an evening’s entertainment floating amidst the light transmitted by decorative paper lanterns and the full June moon.

Everett Shinn (1876-1953)

Couple Among the Lanterns

Cover illustration for Vanity Fair (June 1, 1916)

Pastel and watercolor on artist board

Owen Yost Collection, Florida

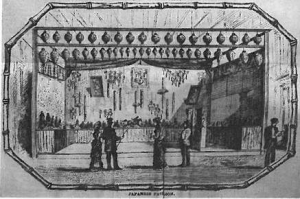

What intrigues me most about this illustration are the paper lanterns bobbing from the tree’s branches. After the opening of Japan to the West in the mid-1850s, trade materials soon arrived in Europe and America along with various dignitaries. While the showman P. T. Barnum put some of the Japanese artifacts on display in his American Museum, it was not until after the Civil War that Japanese culture and artifacts began to have an effect on American taste.* By the time of the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition of 1876, Japanese prints were already available in New York and Boston. That fair and subsequent fairs brought a broad awareness of Japanese goods, style, and taste to America, including the inexpensive paper lantern. In the illustration seen below of a view into the Japanese pavilion at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition you can see a double row of lanterns hanging at the entrance into the space.

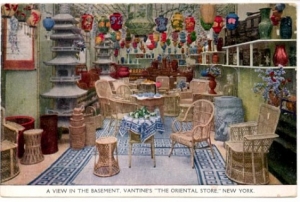

By 1880, in addition to higher end Japanese prints and objects being readily available in American markets, commonplace items such as “parasols and paper lanterns were exported by the tens of thousands and resold by import firms like Vantine in boxes of a hundred each.”** Founded in 1869 by Ashley Abraham Vantine, Vantine’s Oriental Store was a New York emporium that specialized in imported oriental goods from Japan, China, India, Persia, and the East. Below is a postcard photo of the basement display in Vantine’s New York store with samples of paper lanterns hanging from the ceiling.

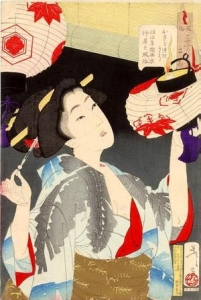

photo of Japanese Lantern Makers Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (1839-1892)

32 Aspects of Customs & Manners of Women Looking Capable

Wood block print

So along with Japanese prints displaying paper lanterns in Japanese life and photographs of Japanese lantern makers as seen above, the easy availability of the paper lantern helped it to become a ubiquitous element in illustration and art. Think of John Singer Sargent’s famous 1885-86 painting, Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose (in the collection of the Tate in London) of two little girls in their summer white dresses lighting the trail of paper lanterns that illuminate the garden as dusk descends.

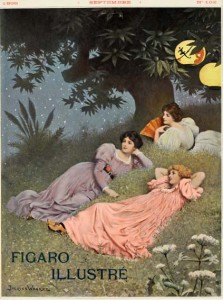

Frederick J. Garner (1883-1962) Jacques Clement Wagrez (1846 or 50-1908)

Woman with Japanese Lanterns Ladies laying on the grass under a tree with lanterns

Cover illustration for The Green Book Magazine Cover illustration for Figaro Illustré (September 1898)

v. 22, #3 (September 1919)

Another illustration example was created by Frederick J. Garner for the cover of The Green Book Magazine September 1919 issue (see above). Once again a pretty woman in a summer white gown carries two more Japanese paper lanterns to join the myriad hanging in the night sky. Compare that roaring 20s-ish image with the French magazine (at the right above) from 20+ years earlier. And here are the commonalities of such illustrations—they typically portray a summer’s evening and the people depicted wear summer clothing, either white in color or at least pastel.*** Like fireflies, the light-filled summer night is a fleeting time that can warm our imagination for many years. As we know, in the dark of a summer’s night, anything is possible—even a man and a woman perching among the lanterns on the bough of a tree.

* Julia Meech and Gabriel P. Weisberg, Japonisme comes to America: the Japanese impact on the graphic arts 1876-1925 (Rutgers, NJ: The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 1990): 16.

** William Hosley, The Japan Idea: Art and Life in Victorian America (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1990): 76.

*** Because Sargent had the young English girls depicted in Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose pose daily at dusk only for a few minutes well into the early winter months of 1885, they wore sweaters under their summer dresses and the garden’s dying flowers were replaced with artificial ones. Sargent resumed working on the canvas in the summer of 1886 and finally finished the painting at the end of October 1886.

June 12, 2014

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum