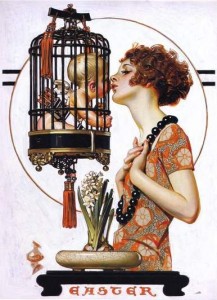

J. C. Leyendecker (1874-1951) | Woman Kissing Cupid, 1923 | Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post (March 31, 1923) | Oil on canvas | The Kelly Collection of American Illustration

Recently one of the students in the graduate class in Illustration Practice Stephanie Plunkett and I are teaching at MICA in Baltimore, asked why Leyendecker would have used a caged cupid kissing a pretty woman for an Easter week cover illustration for the Saturday Evening Post?

After their initial training at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, in the late 1890s, J. C. Leyendecker and his brother Frank X. studied art in Paris at the Académie Julian. There they were further instructed in the academic tradition that taught copying from ancient casts and engravings, and the study of the work of the old masters.

Joseph-Marie Vien (1716-1809); The Cupid Seller, 1763; OIl on canvas; Musee du Chateau Fontainebleau, on permanent loan from the Musee du Louvre (inv. 8424)

This would have included the work of the early French neo-classicist painter, Joseph-Marie Vien (1716-1809) whose 1763 painting, The Cupid Seller* (seen above) is the most likely source for J. C. Leyendecker’s SEP illustration. Vien’s painting was based upon an ancient Roman wall painting illustrated in the luxurious two-volume Le Antichità di Ercolano published in 1762.** Ancient Roman fresco decorations were of various types: still lives; views of landscapes and cityscapes; images arranged like a picture gallery; and images of the stories of and about the gods. The Cupid Seller image is a more fanciful story about a god than most. The image includes an older or poorer woman carting winged cupids either in a cage or in a basket. She lifts a cupid figure by its wings and shows it to other women in an attempt to make a sale. In Rome, Cupid was said to be the son of Venus (the goddess of love) and Mars (the god of war). As a god of love and desire, the prick of one of Cupid’s arrows could instigate love. So buying a Cupid would conceivably give a woman the ability to instigate love from a man.

The Seller of Cupids from Herculaneum as seen in Le Antichità di Ercolano. Carlo Nolli (1710-c.1785) was the engraver of plates for Le Antichità di Ercolano

So when Joe (J. C.) and his younger brother Frank (F. X.) studied at the Académie Julian they most likely studied paintings of some of the great masters. Many of the same masters their own teachers had studied. Most interesting is the linkage from teacher to student that connects the Leyendecker brothers directly back to Vien. Two of their teachers at the Academie Julian, Jules-Joseph LeFebfvre (1836-1911) and Jean-Paul Laurens (1838-1921), had themselves been students of the academic painter Léon Cogniet (1794-1880); Léon Cogniet had been the student of a student of Pierre-Narcisse Guérin (1774-1833) at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris; Guérin had been the pupil of Jean-Baptiste Regnault (1754-1829); Regnault and the great neo-classicist Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825) had been pupils of Joseph-Marie Vien (1716-1809). Vien was one the earliest painters to absorb the newly revealed classical art of the ancient world and to reflect it in his choice of subjects (such as The Cupid Seller) and in his use of classical decoration and forms in his images.

Why then would Leyendecker choose to make this visual reference in his 1923 Easter cover for the Saturday Evening Post? As our student suggested, it would be more appropriate to use a Cupid figure for a Valentine’s cover rather than as a symbol of Easter.

I think the idea may have been that Easter is the holiday of spring, a time of rebirth and new growth. That concept is clearly indicated in the blooming forced Hyacinth bulbs of spring that sit below Cupid’s cage. So instead of being pricked by Cupid’s arrow, Leyendecker shows us Cupid kissing the pretty young lady as though he transmits a new love to her as part of her Easter/spring promise.

It is interesting that the rest of Leyendecker’s illustration is informed by Japanese and Chinese influences: The fabric of the young lady’s dress is very reminiscent of Japanese kimono fabric and the beads around her neck look rather like Buddhist devotional beads. Cupid’s cage looks as though it came from China, while the Hyacinth bowl and lacquer stand underneath it look as though they should be used for Japanese bonsai display.

Hope this helps!

* The Louvre calls this painting Marchande à la Toilette, a seller of trinkets. Since these trinkets are for the lady’s toilette or boudoir these were meant to be ribbons or items for her adornment.

** Pompeii and Herculaneum had been rediscovered around the 1740s. It took until the 1760s publication of Le Antichità di Ercolano for Neo-classical taste to become widespread.

April 19, 2012

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, RockwellCenterfor American Visual Studies, NormanRockwellMuseum