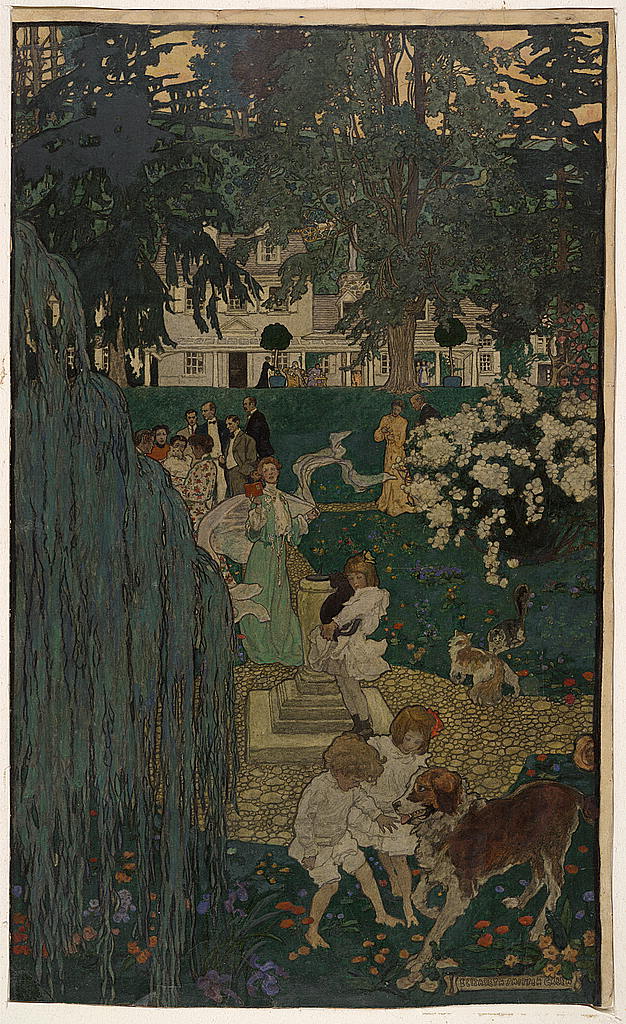

Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871-1954)|Life was made for love and cheer, 1904|Illustration for "Inscriptions for a Friend’s House" by Henry Van Dyke in Harper's Magazine v. 109 (September 1904):501|Watercolor and charcoal on illustration board|Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Cabinet of American Illustration, LC-DIG-ppmsc-04735

In 1901, 30-year old Elizabeth Shippen Green was awarded an exclusive contract creating illustrations for Harper’s Monthly Magazine. That same year Green along with artists Jessie Willcox Smith (1874-1961) and Violet Oakley (1863-1935), and their friend Henrietta Cousins (ca. 1859-1940) took up residence in a 200-acre estate in Villanova, a bedroom community near Philadelphia, called the Red Rose Inn. Soon the household included Green’s parents, Oakley’s mother, three cats, and one St. Bernard dog.*

The house glowed and grounds flourished with the attention and care they received from its new caretakers. So it was natural that Green chose to illustrate the house, grounds, and members of the household when called upon to create an image to accompany poet Henry Van Dyke’s (1852-1933) 1904 poem “Inscriptions for a Friend’s House.” Written early in Van Dyke’s tenure as Professor of English Literature at Princeton University, under four headings this poem delineates the qualities of a good home. The section called “The Hearthstone” is comprised of the lines,

“When the logs are burning free,

Then the fire is full of glee:

When each heart gives out its best,

Then the talk is full of zest:

Light your fire and never fear,

Life was made for love and cheer.”

Green chose the last line as the title of her watercolor and charcoal illustration. The original illustration is colorful and delicate showing the house high on the hill partially screened by the middle ground trees. Various groups of people meander down a winding pebble path that has a sundial in a turning circle of the path. Some of the figures are portraits of Green and the other members of the Red Rose household, including the four cats and St. Bernard dog, Prince. Two children and the dog romp in a bed of flowers in the foreground. In the background, under the house patio’s glass awning a fire roars in an outdoor fireplace, older members of the company take tea, and a woman waters a potted tree.

On the facing page, Green produced a headpiece and tailpiece to accompany the poem’s text. The headpiece at the top of the page appears to be a view through a trio of windows revealing views of a house door, a decorative cornerstone, and the lit fire in a fireplace. At the bottom of the page the tailpiece is the image of the same sundial as in the painting, this time viewed through the trailing branches of a rose-filled bush. Taken together these two page decorations refer back to the four sections of the poem: the house, the door stead, the hearthstone, and the sun-dial.

The mood of the charming frontispiece painting is languid even tending a bit to the art nouveau style with the wafting diaphanous wrap of a central woman in a blue dress. This notion echoes in the gently hanging fronds of a willow and the sprinklings of flowers and flowering bushes dancing through the garden. The feeling that this perfect afternoon indeed this perfect life will go on forever in true only in the painting. Eventually the women loose their lease on the Red Rose Inn and will move to another main-line Philadelphia community, Chestnut Hill. Worse yet, the central foursome suffered a blow in 1911 when Elizabeth Shippen Green married the architect Huger Elliott and moved with him to Rhode Island.

* For more information about these women and their lives see, Alice C. Carter’s The Red Rose Girls: An Uncommon Story of Art and Love (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2000).

August 27, 2009

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, The Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum