Making Meaning of Illustration

By Michele Bogart, Ph.D.

American illustration is an exciting and popular field with tremendous cultural significance, yet paradoxically, one with an image problem. “Illustration,” defined broadly, lacks the centrality and heuristic coherence that the related field of fine art painting has. Partly because of this fact, the endeavor has had difficulty acquiring legitimacy. This situation exists partly because people mistakenly conflate illustration with “Art,” and expect the same aspirations, techniques, practices, and outcomes to apply.

But illustration can’t measure up when interpreted that way. Nor does it even always measure up when examined on its own terms, as images or groups of images, or when examined as part of an entire printed page.

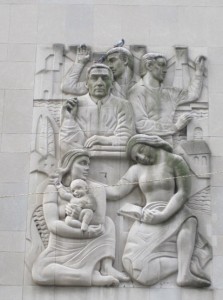

I’d like to offer another way of understanding illustration’s significance (and it is significant), by exploring affinities with American public sculpture—as process and product. Although public sculpture and illustration are not typically associated with each other, my investigations of both have revealed ways in which they relate to each other as forms. The key is to think of both as processes as much as discrete images or objects. Through analysis of process, involving complicated forms of patronage and a host of different interests, illustration and outdoor sculpture may be understood as forms of public culture with many significant dimensions.

Public sculpture, especially Confederate monuments, but not exclusively those, have been extremely controversial of late. Monuments have become targets for criticism in recent months, and even removed. Public officials and all manners of people have reviled them, reacting in part to the subjects depicted and in part to the outlines of the history of their patronage. So, for example, the detractors of the Robert E. Lee monuments in Richmond, Virginia, New Orleans, Louisiana, and Charlottesville, Virginia, have been driven by repugnance for Lee and the certainty that the commissions were symbols of a Jim Crow South: expressions of white supremacism and structurally entrenched racism.

I’ve come at the problem from a different perspective. I don’t dispute what critics have to say, but believe that their outlook, which reduces all of these monuments to the same thing, oversimplifies and levels out the meanings of the different works. I argue these statues are about a lot more than just racial injustice, insisting that they are the physical, aesthetic culmination of diverse and unpredictable human actions. They are dynamic, aesthetically charged, and meaningful imprints of the socio-biographical on place: artifacts whose complex histories tell us much about cities and the people who lived in them. I contend that works should remain in place because they are important historical artifacts, embodiments of processes and negotiations among a range of different parties, both individuals and groups, who bring to the table a host of complex and varied agendas—personal, professional, political, social, and urban, as well as those that are racial, gender, or class-based.

My methods of investigation, grounded in an interest in process, have driven my position on monuments. Although I’ve been lately most vocal lately on that particular issue, I am convinced that the same methods and perspectives can fruitfully inform the study of illustration.

Illustration has been marginalized to some extent for some of the same reasons as has been public sculpture:

- from people taking “personal/political” offense at the imagery

- from people’s unfamiliarity with illustration as a collective, negotiated enterprise, which leads them to interpret “illustration” myopically, exclusively along “Art” lines.

Let me elaborate.

___________

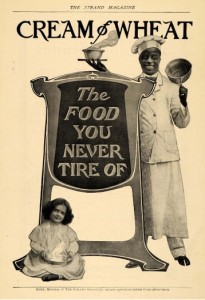

- Like most pre-Cold War era public monuments (though not exclusively), much of what people identify as “illustration” relies upon traditional, figurative forms. As early as World War II, figuration lost its transparency and credibility. Critics dismissed traditional forms for being sentimental, outdated, or spurious myth. And lately, propelled by well-meaning desire to advance social justice—many scholars and critics have taken personal/political offense at imagery that a) trades in violence and vicious racist, sexist, and class-biased stereotype b) that do the bidding of clients with corrupt or evil intentions, or c) that produced outcomes now deemed spurious or otherwise socially unacceptable.

As with some monuments, some forms of unpalatable illustration make people uncomfortable; they condemn or strive to censor it. Yet there is absolutely no reason to assume that appreciation of such works in the present day necessarily entails condoning or admirating their subject matter. The full range of circumstances factoring into illustration images’ production and signification, their successes and failures as modes of text enhancement or as persuasion, are in themselves sufficient reason for acknowledging their significance and for studying them thoroughly, beyond whatever unpalatable meanings they may have. There are in fact numerous ways of exploring the artifacts that go beyond assessing their “authenticity”—a standard used (naively) to engage with fine art. It is misguided to marginalize public art forms based on the perceived “truthfulness,” “depth” or superficiality of their subject matter, their degree of readability or accessibility; their reliance of traditional forms like the figure; their role as an instrument of commerce or propaganda. In short, as with public art, the worthiness of illustration should not be measured according to how suitably it lives up to today’s ethical, political, or aesthetic standards. Like monuments and works of public sculpture, illustration is an enterprise whose genesis and material forms should be thoroughly excavated. Taking cues from public sculpture scholarship may help to see things in a different light.

- Understanding and appreciation of American illustration’s history have also been curtailed to some extent by a tendency to analyze its significance in terms that center on its “Art” side. There’s an overreliance upon the notion of the independent artist, who creates unique, original pictures. Formal aesthetic excellence—framed along traditional art historical lines—remains prioritized as a measure of illustrations’ historical merit. Thus the productions of “name brand” artists like Maxfield Parrish, Norman Rockwell, McClelland Barclay, and Paul Rand have received far more attention than the anonymous illustrators, designers, and “layout men” who fashioned influential but mundane advertisements and magazine covers from 1900 into the age of television. Investigations of the former have focused on analysis of discrete images, divorced from the full printed page, and from the matrices of product-artist-client-agency, without which familiar artists’ images could not have existed.

Building upon the perspectives I’ve brought to the history of public sculpture, I want to argue for a fuller, more encompassing perspective on the history of illustration than we presently have. In addition to monographic work on specific artists, the field needs detailed analyses of image aesthetics and creative activity that are situated within a broader matrix of image and design labor, production, and reception, circumstances which investigate illustration not merely as images but also as process.

For sculptors and illustrators working in the public realm in the twentieth century United States, access to distribution and display of their work was a form of bargain. Realization of projects, and hence the meaning of the images themselves, involved what Douglas Dowd has characterized as “negotiated settlement” among many different parties. Although dissimilar in certain obvious ways (illustration is two-dimensional; public sculpture is three-dimensional), the two fields involved resolving some of the same cultural problems. Both sculptors of monuments and illustrators for mass print media had to grapple with tensions between their own artistic identities, ingrained through artistic training and recapitulated culture-wide—and the demands of their clients, work environments, and overall practice. Neither illustrator nor sculptor was independent. Both areas of practice entailed communicating, through image, text or inscription, and design—ideas and visions that were developed and implemented through a collective process, and that aimed to reach large audiences of indeterminate constitution, scope, and scale, in ever-changing contexts with hundreds of permutations. Both illustrators and sculptors strove to make meaningful statements that complemented or enhanced textual meanings that were governed by different kinds of factors, some economic, some political, some artistic, but that that decidedly could not offend (unless the picture was reproduced in Playboy or Mad).

The collective, negotiated aspects of both public sculpture and illustration enterprises make them significant; the circumstances merit nuanced, detailed investigation and unpacking. Public sculpture derives meaning from a full investigation of its forms, patrons, urban historical and political contexts, its landscape and architectural surroundings, and its audiences’ responses. Illustration work is likewise a function of multiple factors, involving biography, practice, and subject matter, but certainly not limited to them. As with monuments, an informed examination of illustration will look at not only who the artists/designers were, their patterns of training, and the media, styles and techniques that they employed, but also at the full patronage matrix: the interactions among artists, agencies and sponsoring organizations, companies, and clients, along with all the other intermediaries. Local and national politics and broader social events need to be taken into account, as well as the broader overarching perspectives that stem, in hindsight, from considerations like race, class, and gender inequities, preoccupations that motivate many present-day inquiries. The task of the scholar is to compile as much of this evidence as possible, analyze and interpret its significance, and offer new ways of making sense of illustration.

Let me elaborate briefly on some of the factors that warrant taking a different approach to thinking about illustration.

Clients, Products, and Purposes:

With illustration, as with public art, the specific form of patronage and image product are factors that must be accounted for. Memorials commemorating tragic deaths differed from monuments celebrating the life of a notable individual or a national triumph. Those commissions turned on different motivations, circumstances, and often (though not always) involved different people. So too, design and illustration of fiction, advertisements, animation story boards, and record album covers all were motivated by different aims; they entailed different types of practitioners, training, technologies, suppliers, media, techniques, negotiations, and solutions. The nature of the images also was varied within media and across media, as well as according to location: a relief for a 1950s court building differed noticeably from a temporary display of cutting edge art in a park.

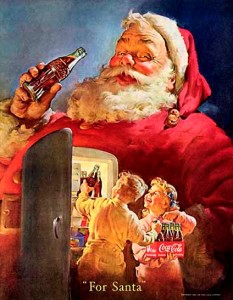

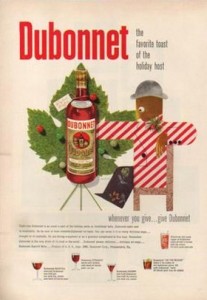

Applying the same concerns to illustration, and focusing just on advertising for example, there is particular need for studies about the promotion of specific products. A Haddon Sundblom billboard advertisement for Coke communicated differently than a magazine advertisement for Hoover vaccuum cleaners or Jell-o, or Paul Rand’s illustrations for Dubonnet.

Investigations of the client-artist relationship and product histories are needed for them all. We need to know more about the people involved in selling these products, and the entire realm of production and distribution; the organization of the work of advertising in relation to that broader realm of production; and the socio-cultural and political circumstances in which that all unfolds. As with public art, there is also need for detailed analyses of how images operated: how their formal and iconographic components communicated a range of meanings. Detailed analyses of the advertisements are needed to understand how the client-artist process culminated in pictures that communicated in particular ways, and to assess how effective or meaningful they might have been.

Biographies and Practitioners:

As a collective process, illustration needs more studies of individual biographies and career developments, not only of illustrators, but also all those involved with the realization of projects: the art directors, “layout men,” copywriters, and clients. These concerns invariably overlap with those of “Clients, Products, and Purposes,” mentioned above. Biography enables us to see how individual lives affected careers, were enmeshed with the organization and labor of image production, and motivated the practices and semiotics of visual communication. The relationships and histories all contribute to motivating the meaning of the pictures beyond their obvious subject matter. Sometimes conflicting or competing interests, combined with along with broader socio-historical circumstances, affected the design, reception, and significances of a project.

Examination of such issues is needed at both micro and macro levels; discrete studies are needed to start out with, and then comparative investigations, with integrative analysis of broader patterns. If we look at Norman Rockwell’s career as an advertising freelancer or employee, for example, and then compare his activities with contemporaries like John Falter (1910-1982) and Douglass Crockwell (1904-1968), or with the work of anonymous designers within advertising agencies or companies like the Charles Cooper Studio, we will end up drawing conclusions that are different than those grounded in an approach that prioritizes Rockwell’s art work as distinctive. Or take the work of record cover album designer Alex Steinweiss (1917-2011). Examination of the realms in which he operated can teach us much of a sociological nature about the organizational structure of the modern corporation, the history of sound recording technology from the 1930s into the 1960s, about one individual’s biographical and artistic trajectory to designing for that medium, and about the challenges of designing for that form of promotion.

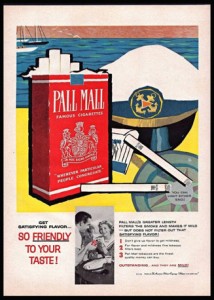

On another front, one could explore, individually, the respective art and careers of Gloria Stoll Karn (1923- ) and Mary Blair (1911-1978). Analysis of Karn’s work of the 1940s would provide insights into the pulp magazine industry; the aesthetic operations of pulp covers’s sensationalist imagery; and of the differences, if any, between the kinds of assignments given to women versus men). Blair’s career would shed light upon the work worlds of the Disney animation studio; on the tobacco industry and the promotion of cigarettes in the late 1950s; and upon the aesthetics of and rationale for a distinctive modernist collage-like line style of painting when applied to advertising design pitched at smokers. Beyond that, however, comparisons among the careers of Karn and Blair and others could further inform us about the opportunities and challenges faced by women artists who entered into the commercial image industries from the Depression through Cold War eras. Add biographical information about advertising agency personnel to all of this mix, and one acquires a rich and far more complicated idea of the complicated motivations and interpersonal dynamics underlying illustration practices and products.

“Illustration” like public art, is collectively-generated material culture that has many dimensions. Yes, some illustration is about racial hatred and about ethnic and gender inequities. And yes, it is also about Art: about standout artists and aesthetically compelling pictures that now sell for millions. But as I’ve sought to demonstrate here, “illustration,” as negotiated process, is also about far more than just that. The various factors I’ve mentioned above all emanate from, circulate around, and in turn, influence illustration as an endeavor. Cumulatively, the complex worlds of illustration reveal its centrality as part of American culture. Understood in this light, illustration’s cultural significance is self-evident and indisputable.

About Michele Bogart

Michele H. Bogart. Ph.D. has taught art history and American visual culture studies at Stony Brook University since 1982. Bogart is author of Public Sculpture and the Civic Ideal in New York City, 1890-1930 (1989/1997), recipient of the 1991 Charles C. Eldredge Prize; Artists, Advertising, and the Borders of Art (1995); The Politics of Urban Beauty: New York and Its Art Commission (2006), and Sculpture in Gotham: Art and Urban Renewal in New York (2018). She has been a Guggenheim Fellow and Terra Foundation Visiting Professor of American Art at the JFK Institut, Freie Universität von Berlin. From 1999 through 2003 she was Vice President of the Art Commission of the City of New York (since renamed the Public Design Commission), the City’s design review agency, and presently serves on the PDC’s Conservation Advisory Group. She is also a member of the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies Society of Fellows.