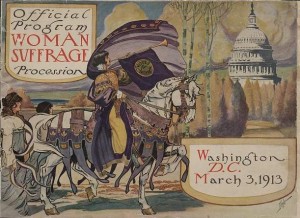

Ben M. Dale (1889-1951)|Cover illustration for the| Official Program Woman Suffrage Procession|Held Washington, DC, March 3, 1913|Original artwork in private collection.

In the first decade of the 20th century American Suffragists paraded a lot. The archive of The New York Times has thousands of articles about various Suffragette marches and processions. Even so, the march this program chronicled was distinctive. Held in Washington, D. C., the parade of between 5,000 and 8,000 suffragettes processed with about 24 floats, 9 bands, 4 mounted brigades, 3 heralds, and 6 chariots from near the Capitol to the Treasury Building the day before Woodrow Wilson’s Presidential Inauguration. Wilson’s inauguration brought half a million citizens to the nation’s capitol to participate in that event. Even so, when Wilson arrived by train the day before the event, there was no crowd there to greet him, they were instead witnessing the Women’s march.*

This parade was organized by Alice Paul, a twenty-eight year old woman from New Jersey who had lived in England and participated in the suffrage movement there. When she returned to the United States, Paul chose to attempt to break the Congressional stalemate over women’s suffrage by grabbing the country’s attention already focused on the district for the inauguration. The parade, or as they called it, the procession, was organized in nine weeks time. In addition to chairing the organizing committee, Alice Paul also raised the money to pay for the floats, banners, speakers, and a twenty-page official program. The total cost of the procession was close to $15,000.** This illustration was created for the cover of the official program of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association procession, showing a woman riding horseback dressed in elaborate attire including a billowing cape and blowing long horn, from which is draped a “votes for women” banner with the dome of the U. S. Capitol building in background. Even the horse is dressed-up wearing a variant of medieval cloth barding. The cover was done by a young artist named Benjamin M. Dale. Dale studied Industrial Arts at the Philadelphia Museum School

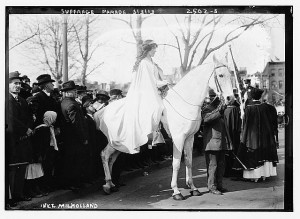

According to a drawing delineating the organization of the march by illustrator Winsor McCay and published in the New York Evening Journal, the horsewoman leading the parade was Mrs. Richard Coke Burleson (“The Grand Marshall, Mrs. Richard Coke Burleson, the wife of an army officer and a splendid horsewoman, . . . .” *** ). The lawyer, Miss Inez Milholland, who was committed to workplace reform, rode the second horse.

Inez Milholland on horse in Suffrage Procession 3/3/13|Photograph, March 3, 1913|The Library of Congress|George Grantham Bain Collection (LOT 11052-2).|Prints and Photographs Division. LC-USZ62-77359

So why a picture woman dressed as a knight and serving as a herald on her horse as the symbol of this suffrage parade? Perhaps it’s a mixture of things. In part it reflected those costumed participants of the parade who represented ideas and ideals (Columbia, Justice, Charity, Liberty, Peace, and Hope) as well as those who wore the costumes of their occupations as they walked the parade route. Another way to look at Dale’s cover image is to see the heralding woman in the guise of a medieval knight (or even modern day Joan d’ Arc) implying that the women involved in this march have questing natures seeking goodness, honor, and societal perfection. Or maybe its meaning is intended to simply be that the women on this march were warriors for the right to vote.

* Gail Collins, “Women’s Suffrage” in The New York Times: The Complete Front Pages. Found at https://www.nytimes.com/info/womens-suffrage/?scp=4&sq=%22Wilson’s%20inauguration%22&st=cse

** Sheridan Harvey, “Marching for the Vote: Remembering the Woman Suffrage Parade of 1913” in American Women: A Library of Congress Guide for the Study of Women’s History and Culture in the United States (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 2001): 35.

*** “5,000 Women March, Beset by Crowds” New York Times (March 4, 1913)

February 24, 2011

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum