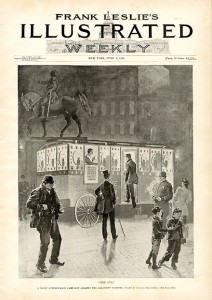

Charles Broughton (1864-1945)|The Owl, 1893|Cover illustration for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly v. LXXVI, no. 1968 (June 1, 1893)|Illustration image from the collection of the Culinary Arts Museum at Johnson & Wales University, Providence, R.I., 2008.156.0001

In New York City in January of 1893 the Church Temperance Society decided to abandon the various coffee houses they had been running. They instead dedicated their funds to operating a night lunch wagon that would serve hot food and beverages for working people on the street from 7:30 pm through 4:30 am. At this time restaurants closed at 8 pm so the alternative location to obtain a meal was a saloon. The commentary about this image in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly offers a different reason for the Temperance Society’s experiment. According to the article “. . . the proposal of the excise commissioners of New York to issue two hundred all-night licenses for saloons . . . .” prompted the society’s response. * This experiment proved so successful that the Women’s Auxiliary of the Church Temperance Society opened more lunch wagons around the city. The initial estimate of the cost of fitting out one of the lunch wagons and opening it for business was around $600.**

The Women’s Auxiliary of the Temperance Society procured a gaily decorated lunch wagon and permission to stand it in Union Square where it served tea, coffee, milk, sandwiches and the like for 5 cents each. The all night eatery proved to be so successful that the Temperance Society opened others including one that stood in Herald Square. It was noted in the New York Times that the Herald Square night lunch wagon supplied 67,600 meals in 1894 “and made a profit to the society of $1,100.” ***

Lunch wagons were more sophisticated versions of lunch carts. Not only were they moveable like their antecedents but they provided easily accessible hot food at night after other restaurants had closed. The first enclosed lunch wagon was open for business in Worcester, MA in 1887. The following year another Worcester young man built a lunch wagon “. . . and called it the Owl. As with many wagons of the time, such as the Twilight Café and the Star, their names were a play on the nocturnal hours the diner kept.” **** In the case of this lunch wagon it really was called The Owl, and its windows were decorated with the image of an owl seated in a crescent moon surrounded by stars. While these wagons were meant to be moveable, years later some New Yorkers complained that they were permanent fixtures.

It is interesting that the illustrator, Charles Broughton (a Canadian who first studied in Toronto and after his move to New York continued at the Art Students League and at the National Academy of Design) provided a visual reference for the location of the lunch wagon in his illustration. In the night shadows behind the wagon stands Henry Kirke Brown’s 1856 equestrian statue of George Washington. In 1893, at the time of this illustration, the monument still sat off the southeast edge of the park at the juncture of Fourth and 14th Street in a fenced enclosure in the middle of the street. *****

Henry Kirke Brown (1814-1886)|Equestrian Statue of George Washington, 1856|Located in Union Square, New York City|This was the first equestrian statue of Washington (photo, c. 1870)

Bart Kennedy’s text that accompanied this cover illustration reveals his interpretation of Broughton’s fascinating picture. Kennedy describes the people in the vicinity of the lunch wagon as “. . . belated women, men who are rounders, tramps, policemen, and other specimens of the varied human driftage of our cosmopolis.” * The choice of the Union Square site by the society was inspired, as Broughton shows us, since General Washington’s right hand is raised in benediction—meant to represent blessing the retaking of New York from the British by the American troops in November of 1783—it also visually implies George’s blessing on the action of the Temperance Society.

My thanks to the Culinary Arts Museum at Johnson & Wales University in Providence, R.I., for their assistance.

* Bart Kennedy, “The Night Lunch-Wagon” in Frank Leslie’s Weekly vol. LXXVI, no. 1968 (June 1, 1893): 351.

** “Coffee House and Lunch Wagon: Projects Urged by the Church Temperance Society” The New York Times (January 18, 1893).

*** “Is Proud of Its Record: Thirteenth Annual Meeting of the Church Temperance Society” The New York Times (January 24, 1895).

**** Richard J. S. Gutman, The Worcester Lunch Car Company (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2004): 9.

***** In 1930, following overall improvements to the park, and to better protect it from vehicular traffic and pollution, the statue was moved its position of centrality on the south side of the park.

February 10, 2011

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum