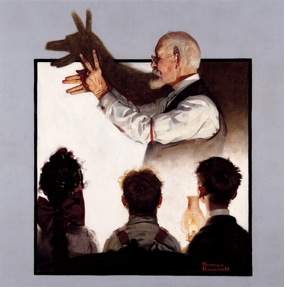

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)|Shadow Artist, 1920|Cover illustration for The Country Gentleman (February 7, 1920)|Oil on canvas|Collection of George Lucas

Norman Rockwell’s Shadow Artist focuses the viewer’s gaze on a white-haired man and the novel shadow figure projected behind him. We witness this amusing scene as if seated behind three young onlookers. While we are not shown their faces, we understand that they are entertained. Accordingly, we remember our own innocent childhood fun. By putting Rockwell’s oeuvre in an art historical context, we can achieve a more complete understanding of his compositional mastery.

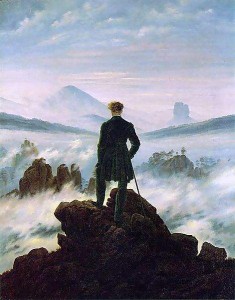

Caspar David Friedrich (1774 - 1840)|The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1818|Oil on canvas|Kunsthalle, Hamburg

In Shadow Artist and many other illustrations Rockwell demonstrates his adeptness through use of the Rückenfigur compositional device. Literally translated, the German term means “back figure,” and it is often used to described figures viewed from behind. The Rückenfigur is often positioned in a landscape and thereby mediates the setting for the viewer. This motif is most commonly associated with the painter Caspar David Friedrich who was a leading proponent of German Romanticism. In paintings like The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog from 1818, Friedrich uses the Rückenfigur in order to invite the viewer to imagine himself in the landscape and experience the sublime potential of nature. We see the peaks of the majestic fog covered mountains from the wanderer’s perch atop a summit. Friedrich directs our point of view in a way that enables us to experience the vista through the Rückenfigur’s perspective. While we cannot see his facial expression, and his gesture is emotionally ambiguous, our experience mimics the sense of awe that the wanderer surely feels as he surveys the panorama.*

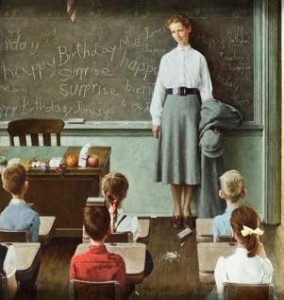

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)|Happy Birthday Miss Jones, 1956|Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post (March 17, 1956)|Oil on canvas|Collection of Steven Spielberg

Rockwell was certainly knowledgeable when it came to the history of art and was likely familiar with German Romanticism.** More importantly, Rockwell used one of Romanticim’s most persuasive compositional elements. By expanding the definition of the term beyond Friedrich’s use we can see how Rockwell successfully adapts the Rückenfigur device for his own purposes, most notably in order to highlight the role of the audience in his works.

In Happy Birthday Miss Jones, he illustrated the class seated at their desks. We see the chalkboard birthday surprise and arrangement of gifts that the students have been preparing in a rush (the fallen chalk indicates the urgency of their act). The students look to their teacher, awaiting her approval. Even the class clown sits perfectly still with an eraser balanced on his head. At this moment, we look over their shoulders to see the beaming face of Miss Jones who is quite obviously moved by their gesture.

These six students serve as Rückenfiguren who mediate the scene for the viewer. There is little question who prepared the surprise, or of its silly yet heartfelt sentiment. We are invited to identify with these characters, and this is easier because they are a sizeable group.*** In their role, we feel a nervous moment of apprehension, hoping our gift will be well received, and elation when we realize that the teacher we so genuinely appreciate is touched by our act. Through the compositional device, Rockwell is able to tell a rich narrative and simultaneously demonstrate the childish wonder and excitement that his works so often elicit from the viewer.

In this way, Rockwell and Friedrich both express a romantic view through the Rückenfigur. While Friedrich conveys the sublime character of nature in a vast landscape and invites the viewer to embrace its beauty, Rockwell examines modern American society with artworks that elicit emotional response from their audience. Although he worked in a popular medium, Norman Rockwell produced sophisticated artworks, which are all the more successful because they compellingly invite us into the artist’s world.

* Joseph Leo Koerner, Caspar David Friedrich and the Subject of Landscape (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990): 163.

** Indeed, Rockwell had three books on the German Romantic painter Carl Spitzweg (1808 – 1885) in his library, and numerous Art History survey books that covered the subject of German Romanticism.

***This seems to be why the majority of his figures seen from behind are not isolated. However, such figures certainly exist. Examples can be found in Little Girl Looking Downstairs at Christmas Party on the cover of McCall’s (December, 1964), or The Connoisseur from The Saturday Evening Post (January 13, 1962). Both illustrations richly use the Rückenfigur to mediate the viewer’s perception of the scene.

March 10, 2011

By Daniel S. Palmer, Ph. D. Student

Graduate Center of the City University of New York