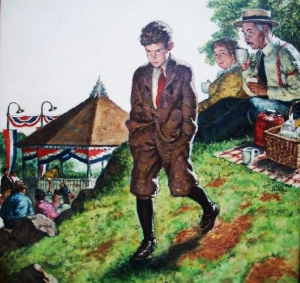

Amos Sewell (1901-1983) | Independence Day, n.d. | Story illustration for an unidentified publication | Oil on board | Shhboom Illustration Gallery

In the 19th and 20th centuries, many American towns had a town square or park where public events and community gatherings took place. European town squares might be paved spaces so that they were suitable for use as open air markets. In the United States these spaces were more often green parks that sometimes had a circular roofed structure, a bandstand, built to accommodate musical performances.* Smaller bandstands were more like a public gazebo, providing a shaded place to rest or to court a girl while surrounded by the park and town.**

During summer months a bandstand might be decorated with patriotic bunting and flags for public holiday celebrations such as, Memorial Day, Independence Day, or Labor Day.*** The same decorative bunting might also be used to decorate the structure if there was a political rally or a public speech by political candidates. It is therefore only a guess that Sewell’s illustration is focused on an Independence Day celebration. Nevertheless it is possible to approximately date the time the story was set. Looking at the boy’s knickers and the older man’s arm garters and straw boater hat, we might date the story-line to the early decades of the 20th century. This guess is reinforced by one of the items seen among the picnic lunch accoutrements: the red painted metal thermos jug.

While the vacuum flask was invented in 1892 by the Scottish physicist and chemist Sir James Dewar, the first commercial vacuum flasks were made in 1904 in Germany by Thermos GmbH, because Dewar failed to register a patent for his invention. From what I can find, that style of thermos jug dates from around the 1920s or 30s and was meant to hold a cool beverage like water or lemonade. Notice that in the photo below of a vintage thermos jug that under the screw-on lid is a rubber gasket stopper. The jug was carried by the wooden turned handle.

Amos Sewell was from California. While working at Wells Fargo bank as a mail boy, Sewell studied at night at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco. After moving to New York he studied at the Art Students League and then at the Grand Central School with illustrator Harvey Dunn. In the early 30s he began working for the pulps and Sewell sold his first illustrations to The Saturday Evening Post in 1937.

In the foreground of this Sewell illustration we witness an older couple pausing during their picnic to watch the boy walk stalk away, his hands stuffed into his pockets and his head down with a contemplative expression on his face. In the background of the image some children (including a girl whose bloomers are revealed under the hem of her dress) climb up the railings of the bandstand as others gather in the park. Inside the bandstand it looks as though there are chairs set up for the evening’s concert. This composition might provide an interesting challenge for someone to create a new story-line for it, using the image as the pivot.

There are a number of unexpected details in Sewell’s illustration. At the pinnacle of the bandstand’s roof is a grouping of decorative curlicues reminiscent of the brackets that decorate trim work on a Victorian residence or the pinnacle of a Victorian tower. I don’t remember ever seeing a bandstand with one of those on top. The other surprising element of this illustration is the obvious detailing of brown patches in the park lawn. Sewell helped to focus our attention on these patches of bare earth by place the largest of them under the toe of the boy’s proper left shoe as he moves down the rock strewn hill. What makes this so unusual to our eyes is that since the 1950s American’s have prided themselves on the weed-free uniform green of their lawns. Seen altogether, Sewell’s visual story reminds us of the multitude of civic celebrations that mark Independence Day even while personal stories continue to unfold.

Whatever and where ever your upcoming Independence Day celebration, may your gathering honor “life, liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.”

* It is no coincidence that in the 1950s the popular television program showcasing the performance of new American music was called Bandstand and then American Bandstand® since a community’s bandstand was where music was performed.

** Think of Fred Astaire and Ginger Roger singing, “Isn’t This a Lovely Day to be Caught in the Rain?” while dancing in the bandstand in London’s Hyde Park in the 1935 movie Top Hat.

*** Some small towns routinely hosted a public reading of the Declaration of Independence during their Independence Day celebrations.

June 28, 2012

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum