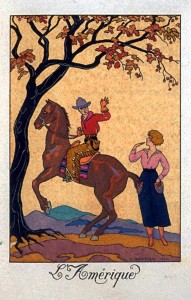

Georges Barbier (1882-1932)

L’Amérique, 1920

Illustration from a 1920 calendar

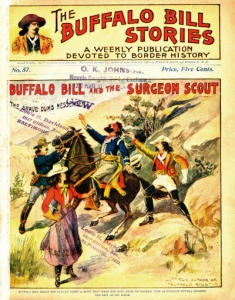

In the late teens and 1920s the French illustrator and designer Georges Barbier produced series of images that were used to decorate annual calendars.* One series focused on the seasons, another on the continents around the world. The image Barbier created to represent the Americas was, as you can see above, a cowboy on a gently rearing horse, waving goodbye to a pretty cowgirl. Portrayed from what could be described as a dog’s eye view with the landscape and mountains in the background seen low to the ground and their distance conveyed with simple changes in coloration.

I can certainly understand why Barbier chose to illustrate the Americas (north) by picturing life in the American west. But the real question must be how did one French art deco illustrator know what cowboys and cowgirls looked like? Most likely Georges Barbier found his inspiration through visuals of the west that were available to him via popular culture of the day.

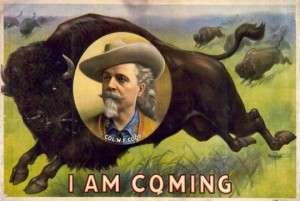

For example, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows were already touring Europe in from 1887 through 1892 and their first performance in Paris was during the 1889 Paris Universal Exposition.** By the end of that decade the show travelled around America with 25 cowboys and a dozen cowgirls.*** Between 1908 and 1913 Buffalo Bill and Gordon W. Lille, known as Pawnee Bill, combined their wild west shows and travelled under a joined name, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Pawnee Bill’s Great Far East.”

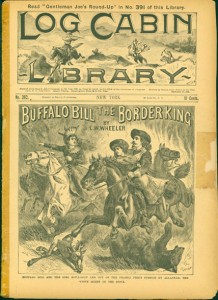

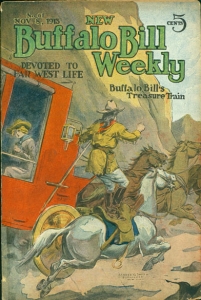

What wild west traveling shows did not address, could be seen and read about in various periodicals and dime novels. Even though most western story magazines did not appear until the 1920s or the 30s, Western Story Magazine began publication in July of 1919. It had previously been a dime-novel library called The New Buffalo Bill Weekly that began publishing in 1913, and its front page was mostly illustration. As you can see cowgirls and cowboys are standard fare. So too are fringed leather garments for the men and short skirts and long boots for the girls.

Popular books about life in the west are also part of our shared culture. For example, the illustrator Mary Hallock Foote (1847-1938) also wrote popular published stories of the west: Led-Horse Claim: A Romance of a Mining Camp was published in 1883 and Coeur d’Alene was published in 1894. Owen Wister’s 1902 novel The Virginian: A Horseman of the Plains was published with illustrations by Arthur A. Keller. And Edgar Rice Burroughs’ first western novel, The Bandit of Hell’s Bend, was published in 1926 with a frontispiece illustration by Modest Stein.

Even early movies help to contribute to our universal notion that we know what life was like in the west and how cowboys looked and acted. In the 1890s Thomas Edison’s “Black Maria” studio was producing short westerns such as Annie Oakley (1894) and Buffalo Bill (1894). In 1903 the silent film The Great Train Robbery brought the danger of the west to the public. Throughout the teens, movies about cowboys and their girl friends were rampant , for example Owen Wister’s story The Virginian was brought to the silent screen in 1914. In 1915 an American western, The Girl of the Golden West, was produced from a 1905 play by David Belasco that he later turned into a novel. In 1910 that play was turned into an opera by Puccini. And by 1919, 41 western film stories were produced in the U.S.

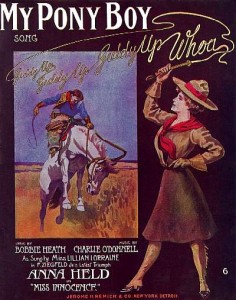

Heck, even the illustrated covers for sheet music contributed to the visual cultural myth!

Andre C. De Takacs (1880-1919)

My Pony Boy, 1909

Sheet music illustration for Charley O’Donnell and Bobby Heath’s ragtime song.

Much as we would like to think that our nation’s visual culture is ours alone, it is clear that much of our visual imagery has been shared around the world.

* “. . . these . . . were from annual almanacs that he illustrated.

These came out annually, beginning in 1917, and featured, along with calendars (unadorned), of course, poetry, blank but bordered pages for writing your secret thoughts, vaguely erotic romance stories, and more. Profusely illustrated, they were clearly the perfect item with which to begin the new year.”

Japonisme blog April 6, 2010 “Serie du Barbier · (the calendars)” See, https://lotusgreenfotos.blogspot.com/search/label/georges%20barbier

** Robert W. Rydell and Rob Kroes, Buffalo Bill in Bolonga: The Americanization of the World, 1869-1922 (Chicago, Il: University of Chicago Press, 2005): 105-17. See, https://press.uchicago.edu/Misc/Chicago/732428.html

*** There is no notation of who traveled with the show or how many of what character while they were in Europe. See, “Wild West shows: Buffalo Bill’s Wild West” by Paul Fees on the web site of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming. https://www.bbhc.org/learn/western-essays/wild-west-shows/

**** To hear the music of “My Pony Boy” and to see a larger image of the sheet music illustration, go to,

https://perfessorbill.com/covers/ponyboy.htm

November 14, 2013

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum