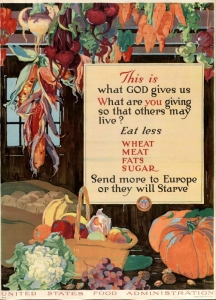

Albert Hendee|This is What God Gives Us, c. 1918|Poster for the USFA|Photo: University of Minnesota Libraries

The Great War (1914-1918) necessitated sacrifices from American citizens and their luxurious way of life. Commodities, such as sugar, which had once been in abundance, became the focus of rationing for the greater good. Restrictions on sugar were especially pronounced due to the removal of Germany and the West and East Indies as viable import sources.* Tactical requirements meant ships and manpower usually used to import sugar were urgently needed for the war. Thus, loyal Americans were encouraged to do their patriotic duty to “Save On Sugar” in aid of the Allies and U.S. military.

To promote rationing measures, the United States Food Administration (USFA) was created in August of 1917 by the Food and Fuel Control Act.** This organization launched a public relations assault on multiple fronts, which included cookbooks, textbooks, treatises and a series of important propagandistic posters. These posters were designed through a collaborative process in which illustrators used their skills to voluntarily contribute to the war effort.*** The USFA’s poster campaign encouraged limits of sugar consumption with creative visual techniques that made a profound impact on the diets and minds of Americans.

An excellent example of these bold images can be seen in the 1918 USFA poster This is What God Gives Us by A. Handee. It combines Handee’s masterful illustration technique with text discouraging consumption of valuable commodities. Instead of selling a product, many USFA advertisements dissuade the public from using sugar, instead promoting only abstract concepts of nutrition and patriotism, at times with religious overtones. This is visually reinforced by Handee’s rich depictions of abundance showing bountiful foods which could be locally harvested. Voluntary rationing is thereby encouraged with patriotic text and meticulously drawn illustrations endorsing healthier alternatives.

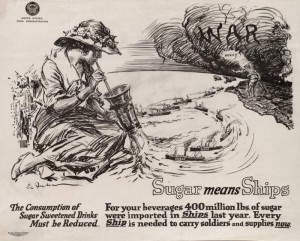

Ernest Fuhr (1874-1933)|Sugar Means Ships, c. 1918|Poster for the USFA|Photo: University of Minnesota Libraries

USFA posters also stressed the necessity of sending commodities, specifically sugar, to Europe. This is strikingly depicted in Ernest Fuhr’s Sugar Means Ships poster. Fuhr was a pupil of William Chase who studied art in Paris and produced illustrations in black and white for a variety of newspapers and juvenile magazines.**** Like many other patriotic illustrators at the time, he turned his attention to the war effort. This resulting image shows a lazy, languid urban woman wearing a fashionable hat as she takes a large gulp of a sugary drink. This sucks ships toward her and away from a desperate soldier in the European fog of war. The poster quite effectively demonstrates the strain that excessive sugar consumption has on the war and appropriately encourages patriotic citizens to reduce their intake.

The effectiveness of the talented artists illustrating the US Food Administration’s campaign can be judged in the spectacular array of eye-catching examples and their influence on American illustration. Additionally, these artworks have had a lasting effect on the medium of the poster and our nation’s nutritional mindset.***** In more measurable terms, the USFA’s Sugar Board earned a surplus of $30,000,000 for the government and stabilized prices and consumption, largely due to these posters and the rest of the successful public relations campaign. Without a doubt, the triumph of these artworks was in their graphic directness and ability to successfully persuade the citizens of America that all they had to do to be an indispensable part of the collective war effort was, quite simply, to “Save on Sugar.”

* William Clinton Mullendore, History of the United States Food Administration, 1917-1919 (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1941), 110.

** 40 STAT. 276 (1917).

*** Mainly, the Division of Pictorial Publicity of the Committee of Public Information, headed by noted artist Charles Dana Gibson, served as the organizational body for wartime illustrators.

**** Walt Reed, The Illustrator in America, 1900-1960’s (New York: Reinhold Pub. Corp., 1966), 87.

***** For additional information see Maurice Rickards, Posters of the First World War (New York: Walker, 1968) and Harvey Levenstein, Revolution at the Table: The Transformation of the American Diet (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988).

October 7, 2010

By Daniel S. Palmer, Ph. D. Student

Graduate Center of the City University of New York