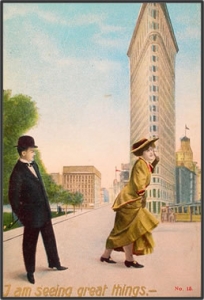

William Balfour Ker (1877-1918)|XMAS 1905, 1905|Cover illustration for Life magazine (December 7, 1905)

In 1902 the Chicago architect Daniel Burnham finished construction of the Fuller Building in New York City; it was named after the company’s founder, George A. Fuller even though Mr. Fuller died two years before the building was begun. It is located at 175 Fifth Avenue, off of 23rd Street where Fifth Avenue and Broadway cross at the far southwest corner across from Madison Square Park. It is better known as the Flatiron Building because of the shape of its foot print; its other common but derogatory name was ‘the cow catcher.’ This skyscraper nevertheless caught the imagination of a variety of artists and became an icon of early 20th century popular culture of New York.

The photographers Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen both took spectacular images of the building not long after it was completed. Stieglitz’s image shows the tall building rising up atmospherically out of the snow-covered trees in Madison Square Park. Steichen’s vision is also atmospheric and influenced by Japanese art with the expressive branches of the winter bare trees patterning the surface with a view of the skyscraper behind the branch scrim.

But what really caught the imagination of city residents and visitors, were the strong winds that spun up around the base of this building. In 1904 the English painter, Sir Philip Burne-Jones, described the Flatiron Building as, “One vast horror, facing Madison Square . . . distinctly responsible for a new form of hurricane, which meets unsuspecting pedestrians as they reach the corner, causing them extreme discomfort.” * The same winds that swirled around the base of the building had a tendency to lift women’s skirts, allowing urban voyeurs to catch a glimpse of women’s ankles usually hidden under their hems. The winds also kicked up unpleasant clouds of dust. The painter and illustrator John Sloan, a newcomer to New York, recorded this phenomenon in a painting, The Dust Storm, 1905 done early in his tenure in New York city. Policemen walking the beat around the base of the building tried to hustle young men along who preferred to loiter so that they could watch women’s skirts blow about in the building’s downdrafts. According to one of the interpretations of the expression, cops called their hustle the ‘23 skidoo.’

The charming cover illustration of the Flatiron Building created for a December 1905 issue of Life magazine by William Balfour Ker, employed the building’s windy nature to create a holiday specific image. Instead of chronicling the breeze at the base of the building, Balfour Ker imagined that same turbulence at the top of the structure. The forceful winds cause Santa’s reindeer to spin and twirl and loose their (non-existent) footing. Even Santa’s sleigh has twisted and tipped in the brisk breeze, causing gifts to tumble from his packs. Balfour Ker visually tells us that now in the modern world of 1905, we can all expect that Santa Claus will have new challenges to meet as buildings get taller and turbulence takes over not only the streets, but now too the skies.

Hope your holidays are wonderful and your gifts all arrive undamaged.

* Sir Philip Burne-Jones, Dollars and Democracy (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1904). For an extensive history and images of this phenomenon see, Nancy Mowll Mathews, “The City in Motion,” Nancy Mowll Mathews, Moving Pictures: American Art and Early Film 1880-1910 (Manchester, Vermont: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Williams College Museum of Art, 2005): 117-29.

December 16, 2010

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum