Early in painter Edward Hopper’s career he earned his living making illustrations. As a young man his parents insisted that Hopper study commercial art in order to ensure the means for earning a living. While Hopper did not love seeking or doing illustration commissions, his work, such as those shown here, is compelling with an immediacy at odds with our sense of his imagery as a painter.

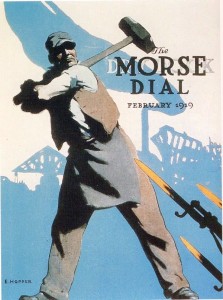

In 1918 the National Service Section of the United States Shipping Board Emergency Fleet Corporation sponsored a competition for a propaganda poster design through the New York Sun. During the war The Morse Dry Dock and Repair Company, located in Brooklyn, was one of the country’s largest ship repair and refit facilities and was at that time primarily focused on doing work for the U. S. government and military. Like other corporations during this period, Morse produced its own in-house periodical, The Morse Dry Dock Dial, that was mailed to employee’s homes monthly.

The editor of the Dry Dock Dial was Bert Edward Barnes, a professional newspaper man. According to Edward Hopper scholar Dr. Gail Levin, it was Barnes who persuaded Hopper to enter the contest to produce a new propaganda poster in aid of the U. S. war effort.* To assist Hopper with his design, Barnes also arranged for one of the company’s employees, Peter Shea, to model for Hopper. In order to facilitate Hopper’s work in his studio, a photo was taken of Mr. Shea posing with a large sledgehammer swung over his right shoulder.** Since the heavy metal head of the sledgehammer can weigh as much as twenty pounds, it requires a person to use two hands to hold the wooden handle as they swing it by rotating their torso, much like a baseball bat.

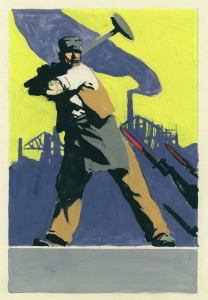

As you can see in Hopper’s study for the poster and in the version later published on the cover of the company’s February 1919 issue of their magazine, Hopper reduced the image components into sections of color. The background scene is rendered in a single tone of blue, against a white or yellow background. The shipyard and a smokestack with smoke pouring out are represented in silhouette without any attempt to create depth or shadow in the image. In the foreground the company worker, dressed in his work clothes and an apron and a cap stands with a sledgehammer poised over his shoulder. Notice how Hopper used a black outline around much of the man’s figure in an attempt to make his form more distinct and powerful. By positioning the hammer head so that it stands out against the white of the sky in the magazine cover and the yellow in the study, it becomes the pivotal focus of the image. Below the man at the right of the image are three orange tipped bayonets threatening the workman and the shipyard. In the study instead of the orange tone, the color of the bayonet’s blades are clearly red—this is suppose to read as bloodied weapons. The worker is active, engaged, and clearly conveys the personal power that represents the actions of the nation.

Hopper’s poster proposal was one of the fourteen hundred submitted to the New York Sun’s competition. To his amazement, he won first prize with an award of $300. Unfortunately armistice was declared before the poster design could be reproduced for distribution. But Hopper’s original art along with the work of nineteen other finalists was displayed in a Broadway facing window of Gimbel’s department store in New York in August of that year. During the run of the display, the New York Sun ran articles about the posters including one titled “The Sun’s Poster Contest Shows Arts Value in War.”***

And finally, in a very smart move, Mr. Barnes used the unpublished poster design as the cover illustration for his corporate magazine’s February 1919 issue, adding the magazine’s name and date of publication to the upper right of Hopper’s design—under the head of the powerful sledgehammer and above the smoke from the shipyard.

* Gail Levin, Edward Hopper: An Intimate Biography (Berkley: Univ. of California Press; New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1998): 108-121.

** This photo was published in The New York Times in an article, “Against Bolshevist Propaganda Among Workmen: Hundreds of Employers Are Issuing Their Own Magazines and Newspapers to Counteract the Influence of the I.W.W. in the Plants” (October 26, 1919).

*** Charles Matlack Price, “The Sun’s Poster Contest Shows Arts Value in War,” New York Sun (August 25, 1918): sec. 3, p. 8, includes a reproduction of Hopper’s poster design.

July 14, 2011

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum