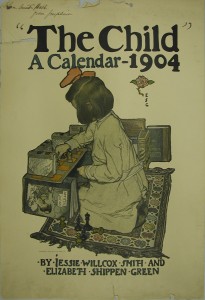

Jessie Willcox Smith (1863-1935)|Warming Feet, 1902|Illustration for The Child, a Calendar, 1903, 1904|Collection Delaware Art Museum, 1977-301-2

Artists Elizabeth Shippen Green and Jessie Willcox Smith met while studying illustration art with Howard Pyle at the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia. Both had extensive art training before their classes with Pyle and were already selling illustrations to the popular press. By 1897, Smith, Green, and Violet Oakley were sharing studio space in downtown Philadelphia. A few years later they, along with Henrietta Cousins, moved to a 200-acre estate in Villanova, PA, called the Red Rose Inn.

In 1902, Smith and Green collaborated on the illustrations for a calendar for Bryn Mawr College. This successful venture encouraged the women to produce another calendar, but this time they self-invested in the project and a 1903 calendar was produced for them by The Beck Engraving Company of Philadelphia (run by Charles W. Beck, Jr.), with a 1902 copyright. They used the same illustrations for a 1904 calendar produced the same way. Subsequently, the New York publishing firm Frederick A. Stokes Company asked the women permission to reprint their calendar art work only this time accompanied by a series of poems written by Mabel Humphrey, a popular children’s author. This was published under the title, Book of the Child.

The cover image for the calendar is called Playing Chess. Created by Elizabeth Shippen Green, it shows a young girl kneeling on an oriental rug as she plays with chess pieces on half of a chess board. The board and play area are constructed using books balanced on their open edges to create walls and foundations around the girl. The only book title that can be clearly identified is a bound copy of the periodical Artistic Japan in the foreground. It was a monthly magazine dedicated to Japanese art produced in London by Samuel (Siegfried) Bing, a Parisian dealer of art nouveau and Japanese decorative arts objects. If you want to think of the little oriental rug under the girls knees as a prayer rug, then you might consider Artistic Japan as a foci of the veneration. Green and Smith were both influenced in the construction of their images by Japanese wood block prints in that they utilized a heavy outline in their illustrations and they often flatten areas of color with no detailed definition. They also both use a Japonesque style of monogram similar to an oriental chop: a signature seal engraved with a person’s name and used to create a legal document. The pink rose above Green’s initials reminds us that they were, as Howard Pyle called them, the Red Rose Girls.

The other page from the calendar pictured above is by Jessie Willcox Smith and is called, Warming Feet. It and two smaller side illustrations decorate the calendar page for January and February. In this cozy scene Smith has young child sitting indoors with stocking feet outstretched toward the glowing warmth of a cast-iron stove. Through the window panes in the background of the image, a snowy street-scene contrasts with the warmth inside. The side illustrations below the primary image of the calendar page, also reference winter activities. On the left, in a very Japanese-like view of a slice of an image, is a child stretched out on the floor enjoying various picture books. The right side illustration is of a boy putting a letter in a tree-hole mail box in a snowy landscape.

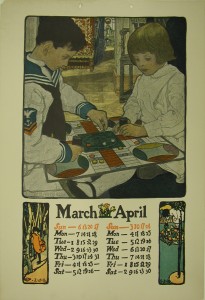

Elizabeth Shippen Green (1871-1954)|Playing Parchesie, 1902|Illustration for The Child, a Calendar, 1903, 1904|Collection Delaware Art Museum, 1977-301-3

Green’s illustration for the March-April page of the calendar shows a boy and girl sitting on the floor with a Parcheesi board balanced on their laps. The board game is an American adaptation of the Cross and Circle game played in India since about 500 B.C. What I find difficult to believe, is that these children are calm and quiet enough to hold the game board on their laps while they play. The side illustrations, also by Green, illuminate March with a wind-blown girl to the left of the calendar sheet, and a girl watering spring flowers to the right of the calendar sheet for April.

The images for these calendar pages were carefully staged by Smith and Green. With props, children and poses in place, Green took reference photographs for she and Smith to use as they produced the illustrations. The actual color prints were produced by a chromotype process first created in 1894 by one of Beck’s parent companies, The Philadelphia Photo-Engraving Company, for whom C. W. Beck, Jr. had been the general manager before acquiring the firm and recreating it as The Beck Engraving Company in 1896.*

* See, George D. Beck, The Economy of Excellence: The Story of The Beck Engraving Company (New York: The Newcomen Society in North America, 1966). In 1908, The Beck Engraving Company would make the very first set of four-color plates which would become the industry standard for recreating color images.

April 8, 2010

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Culture

Norman Rockwell Museum