Founded in 1872, Popular Science magazine’s focus was to bring science to the “educated layman.” The journal featured articles by such famous scientists and inventors as Thomas Edison, Charles Darwin and Louis Pasteur. In the midst of World War I, it is not surprising that the magazine’s cover image and related article focus on how to get better use of our shipping fleets and to be able to reuse the engine area amidship when the bow or stern had been torpedoed.*

The cover for that issue colorfully demonstrates the separation of the ship’s parts as seen from on top of the water. Unfortunately there is no illustrator’s name visible on the cover illustration nor listed in the periodical’s table of contents. But what I find most interesting about the cover image is that the ship is painted in colorful dazzle camouflage. Dazzle camouflage was pioneered by the British naval officer, artist, and illustrator Norman L. Wilkinson (1878-1971). In the U. S. this form of camouflage was sometimes known as Razzle Dazzle and both types were intended as a way for war ships and merchant ships to visually confuse the crew of German U-boats.** The painted diagonals and curving areas of contrasting colors (such as the red and blue pictured here) were meant to make it difficult to gauge a ship’s size and direction. Wilkinson described this as disruptive coloration. The idea for this came to Wilkinson while on submarine patrols in 1917. He realized that since you could not hide a ship on the ocean, a ship would need to be painted “. . . in such as way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as to the course on which she was heading.”***

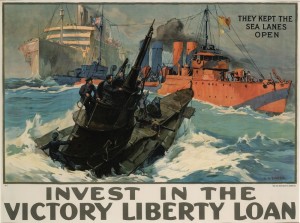

Before 1918 there was not yet much of a public awareness in this country of the color and look of dazzle camouflage.**** It is not until the popular poster created by Leon Alaric Shafer (1866-1940) in 1918 urging Americans to support the war effort through the purchase of Liberty bonds that this protective device became recognizable on the national stage. Shafer produced his poster in support of the “Victory Liberty Loan,” the last of the United States bond issues relating to World War I. This fifth bond was issued in April 21, 1919. Shafer’s poster was pointedly about those ships who helped to keep “. . . the sea lanes open.” In 1919 it was described by Albert E. Gallatin as “. . . an excellent poster, showing an American destroyer coming to the rescue of a transport, about to be torpedoed.”*****

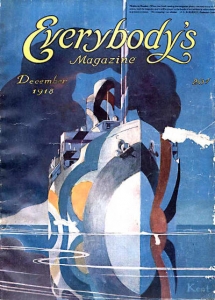

Another image of a ship painted in dazzle camouflage occurred on the December 1918 cover of Everybody’s Magazine. In this case the illustrator, Rockwell Kent (1882-1971) posed the ship in his image as though it was slowly moving toward us, the viewers, through rather still and consequently reflective water. Another difference is that the camouflage pattern is constructed out of red, white, and blue.

The human spirit is basically indomitable. Generally our view of the world causes us to believe that every problem encountered can be solved and every challenge met. Creating and using dazzle camouflage is one form of this notion, as is the idea of “Changing Engines Like a Suit.”

My thanks to Rob Doane, Print Curator at the U. S. Naval Academy Museum for his advice and comments.

*Joseph Brinker, “Changing Engines Like a Suit” Popular Science v. 93 no. 1 (July 1918): p.2-4. One of the article’s drawings illustrates ‘How the engine amidships would float off when the ship is torpedoed.”

**For more information on the origin of Dazzle painting see, Roy R. Behrens, Camoupedia: a compendium of research on art, architecture and camouflage (Dysart, Iowa: Bobolink Books, 2009): 110-112.

*** Norman Wilkinson, A Brush with Life (London: Seeley Service, 1969): 79.

**** “On the cover of the October 12, 1918, issue of The Independent (Vol 56, No 3645) was featured a painting of a dazzle-camouflaged ship. . . with no mention of the artist’s name.” Quote from Roy R. Behrens blog, https://camoupedia.blogspot.com/ And in 1918 the American poet Amy Lowell’s poem “Camouflaged Troop-Ship: Boston Harbor” was published in The Dial. See Behrens, Camoupedia : 426.

***** Albert Eugene Gallatin, Art and the Great War (1919): 38.

June 2, 2011

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum