The End

by Barbara Rundback

The illustrator Howard Pyle understood the essential elements of imagining the termination of a life or illustrating the passage of a lifetime. In the vignette seen below, he pictured an artist (himself really) seated under his umbrella painting the ruins of Fort Ticonderoga en plein air—in the open air. Standing behind the artist is the spirit of Ethan Allan, bearing witness to the past of the fort while watching over the artist recreating that life. In this scene fragment, Pyle ruminated about how the past influences the hand of the present.

Howard Pyle (1853-1911)

Untitled Vignette, 1896

oil on board Delaware Art Museum , gift of Marion Mahony Manning in memory of Mary Poole Mahony, DAM 1991-165

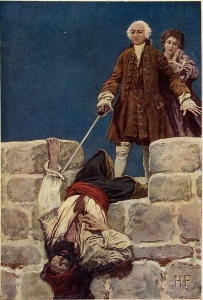

Throughout his career, Pyle imagined many illustrations that visualized death in one way or another. In the illustration below on the left , “Let me go to him!” a man is shown dying by drowning, and to its right, in The Death of Cazaio, another man dies of a sword wound even as he falls from the parapet upon which he tenuously hangs. It is interesting that in both of these illustrations it is the expressiveness of the living that helps us to envision and define the deaths they witness. The caption of the left illustration describes the woman on the ship, the “Lady Betty,” as shrieking. But it is her arm placement and gestures (her right arm lifted to her forehead, palm out, in what we might describe as an Edward Gorey “Woe is me” gesture; and her left arm lifted up in the air with her finger splayed) that convey her distress.* In Pyle’s Death of Cazaio, Cazaio gestures with his right hand toward his wound even as he falls. Standing above him, the victor’s out-stretched left arm echos the position of his sword arm. Behind him stands a distraught woman her hands clenched together resting against the left side of her face and her mouth open as though she has cried out as Cazaio fell to his death.

Howard Pyle (1853-1911) Howard Pyle (1853-1911)

“Let Me Go to Him!” She Shrieked, in Her The Death of Cazaio, 1907

Anguish of Soul, 1901 for Sir Christopher: Story illustration for “In the Second April” by

A Romance of a Maryland Manor in 1644 James Branch Cabell in Harper’s Monthly

by Maud Wilder Goodwin (Boston: Magazine (May 1907)

Little, Brown, and Company, 1901) Oil on illustration board

Oil on board Location Unknown

Delaware Art Museum, gift of Willard

S. Morse, DAM1923-153

In 1903, the students who studied at the Howard Pyle School of Art in Wilmington Delaware** gathered for their weekly drawing class where they worked impromptu on whatever quick assignment Pyle devised. At Pyle’s suggestion three of the students invited the local textile mill owner Samuel Bancroft, Jr.,*** to join them for the first of these classes held at their studio. During that first year of use, Hermann Carl Wall, Arthur E. Becher and William J. Aylward rented the space.

On the evening of March 25, 1903, the members of Pyle’s drawing class sketched their personal interpretation of Pyle’s suggested topic, “The End.” They later presented a portfolio of these sketches to Bancroft bound in a piece of book cloth acquired from the Bancroft Mill.

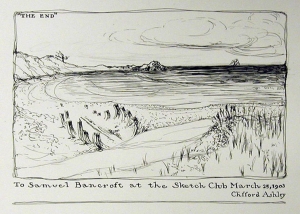

Howard Pyle (1853-1911) Clifford W. Ashley (1881-1947)

The End, March 25, 1903 The End, March 25, 1903

ink on bristol board Ink on paper

Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft

Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935-219.1 Memorial, 1935-222

Pyle’s drawing of this theme is similar to his Death of Cazaio illustration only this time the dead man’s gestures are flipped and the confrontation appears to have been over the results of a card game—notice how Pyle placed the dying man’s head next to the pile of playing cards laying on the bench. Pyle student, Clifford Ashley, focused his version of The End on the rotted remains of a boat decaying on a beach. It is interesting that the boat’s remains also look rather like human ribs creating a double visual whammy. William J. Aylward’s (1875-1956) (not shown here) drawing also pictures the remains of a boat, but in his case a galleon wrecked on a shoal of rocks near the shore.

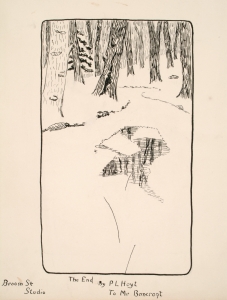

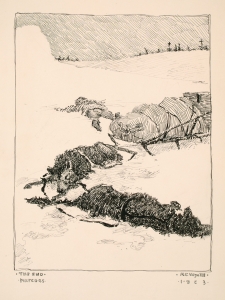

Students Allen Tupper True (1881-1955) and Herman Pfeifer (1874-1931) both illustrated a man dead by hanging. James Edwin McBurney (1868-1955) drew a man dead or dying of thirst is a desert. Stanley M. Arthurs (1877-1950) and Frank E. Schoonover (1877-1972) indicated their concept of The End by showing the end of a journey: Arthurs’ was by way of a stage coach pulling into town and Schoonover’s with an Indian in a bark canoe heading towards the viewer, presumably we are the journey’s end. Philip L. Hoyt and N. C. Wyeth both set their version of the theme in the snow of winter. As you can see below left, Hoyt’s illustration tells its story with minimal imagery because the person, now gone from the picture, has already fallen through the ice of the snow-covered river and all that remains in the reflection of the wintry scene on the as yet refrozen water. Wyeth’s drawing shows the end result of a musher and a couple of his sled team who have succumbed to the all-encompassing northern cold. I like how the bodies of the dogs, the sled, and the man lead you back into Wyeth’s simple scene.

Philip L. Hoyt (1873-1964) N. C. Wyeth (1882-1945)

The End, March 25, 1903 The End, March 25, 1903

ink on bristol board Ink on paper

Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R.

Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935-336 Bancroft Memorial, 1935-335

In the portfolio gifted to Bancroft, you can see a variety of visual possibilities to use when you want to illustrate The End: a battle to the death of two animal-skin clad barbarians; a prisoner in a dungeon; a dead Civil War soldier; performers being dragged from the stage; a jester holding open the last pages of a book that show the words “The End”; and an old couple looking out into a dark landscape—perhaps the metaphorical future. But the one illustration I love the most from this set is the one created by Herman C. Wall. Wall’s name may not be well-know, but he was a perfectly good illustrator and cartoonist. So perhaps it is the bit of black humor in this illustration that appeals to me. His vision of The End was of the mass of the earth falling through the sky in flames (notice the other planets in the background) and because gravity is no more, people fall off the earth in droves.

Hermann Carl Wall (1875-1915)

The End, March 25, 1903 ink and graphite on bristol board Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial, 1935-334

I know you’ll forgive this long meander through this unusual subject, but I chose it as a visual way of letting you know that my tenure as the Curator of the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies is about to come to a close. I am soon to retire. My thanks to all you who have been reading these essays and the rest of the information available on the Rockwell Center web site.

Isn’t illustration wonderful!

* Notice how many other arms are raised up in this picture and how many hands are also expressively splayed out. Illustrator and Howard Pyle historian Ian Schoenherr once commented that this splayed open hand gesture was one of Pyle’s most repeated expressive gestures. So the question is, did Gorey learn to do that by looking at Pyle’s work?

** You will notice that I name in full Howard Pyle’s school. I do this because many out there misunderstand and believe that Pyle’s school was called The Brandywine School. Pyle’s illustration school was never called by that name. The illustrator and illustration chronicler Henry Pitz used that name to indicate both the members of Pyle’s school and after Pyle’s death, the illustrators and artists who continued to live and work in and around the Brandywine area. The Brandywine is a river that runs through Pennsylvania and past Chadds Ford, where the Pyle family had farm property, and down through Delaware and Wilmington, a town on the Delaware River. Sorry this is so convoluted. When Pyle taught illustration for both Drexel Institute from 1894 to 1900 and at his own school in Wilmington, he would sometimes take his best students (male and female) out to Chadds Ford, where his family owned property, for summer classes. One of his later students from the Howard Pyle School of Art, N. C. Wyeth, was so enamored with Chadds Ford and the Brandywine River that that was where he settled and lived the rest of his very productive life. That is where the Brandywine Museum is located. There was never any school of art called The Brandywine School.

*** Samuel Bancroft, Jr., was a Wilmington, Delaware industrialist, landowner, and Pre-Raphaelite art collector. He also owned and rented out the 1607 Rodney Street studio building to Pyle’s students.

August 21, 2014

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum