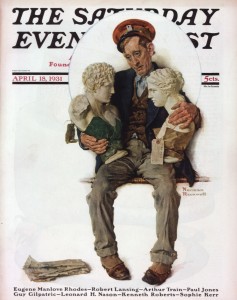

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)|Man Holding Two Portrait Busts, 1931 (aka, Delivering Two Busts)|Cover illustration for The Saturday Evening Post (April 18, 1931)|Oil on canvas|Private Collection

In the Great Depression life was tough for most everyone and any job was a good job. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it. In 1929, the recession hit in August, two months before the stock market crashed at the end of October. By the end of 1929, 3.14 percent of the American labor force was unemployed; this figure more than doubled by the end of 1930 when 8.67 percent of the labor force was unemployed; and by the end of 1931 the unemployment rate was 15.82 percent.*

In the Great Depression life was tough for most everyone and any job was a good job. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it. In 1929, the recession hit in August, two months before the stock market crashed at the end of October. By the end of 1929, 3.14 percent of the American labor force was unemployed; this figure more than doubled by the end of 1930 when 8.67 percent of the labor force was unemployed; and by the end of 1931 the unemployment rate was 15.82 percent.*

When Norman Rockwell created this cover illustration for the Saturday Evening Post early in 1931, Americans in increasing numbers were trying to find anyway possible to secure a paying job. In the case of this illustration, the man is working as a delivery man. His clothing is comprised of ordinary non-coordinated slacks, jacket, and vest over a blue working man’s shirt.** Even though he does not wear a regulation uniform, he does sport an official looking peaked cap on his head. This is a military or service profession cap typically worn by those who wear a uniform. It is constructed with a crown, band, and a peak (also known as a visor). The shine on the front portion of the band and visor indicates that it is made of patent leather making it more durable in inclement weather. Over the lacings of his shoes, the deliveryman wears cloth spats.*** Before they became the height of fashion in the early decades of the 20th century, spats were designed to protect shoes and ankles from mud and water while walking. The deliveryman’s shoes reveal considerable wear, indicating that his spats are incapable of keeping his feet from getting wet.

Tossed on the floor beside this woebegone character is a well-read folded newspaper. The inference is that he has been unable to find another job that either pays better or is less a challenge to his feelings of self-worth. The expression on his ordinary face is mere acquiescent as he sits on some sort of public conveyance holding two marble busts in his arms to be delivered.

His left hand he holds the shoulder of a copy of bust of the Venus de Milo. Venus is the Roman goddess of love, beauty, and fertility. The armless full figure sculpture of this classically beautiful woman is in the collection of the Louvre Museum in Paris. His right hand holds the base of a bust of an Apollo figure, typically shown as a very handsome beardless young man. In part it is the juxtaposition of these two figures of ideal classical beauty to the rather earnest but plain face of the deliveryman, that is the focus of Rockwell’s illustration. Compare the small straight noses of the marble busts to the lumpy, bumpy real nose of the man; the smooth unblemished faces of the sculptures to the red-rimmed puffy eyes and the worry lines etched across his forehead. To make the point of the deliveryman’s human imperfections further, Rockwell gave him large ears that obviously stand out from his head. This is truly a comparison of the ideal to the real.

Roman Patrician Carrying Two Ancestor Busts, 1st C. AD|Marble|In the collection of the Palazzo dei Conservatori in Rome

There is one more visual reference you may not recognize. By portraying the deliveryman holding these male and female busts in his arms, Rockwell was making a bit of a humorous connection to the 1st century AD marble sculpture of a Roman Patrician Carrying Two Ancestor Busts. In ancient Rome, wax death masks, called an imago, were made of deceased family members. Families of senatorial status prominently displayed the imagines of their distinguished ancestors in one of the public rooms of their houses. Eventually wax masks were copied in stone. Family members would carry these busts in public events, such as a funeral so that the “whole” family participated. The more imagines a family could display, the greater its status.

Despite the cover illustration’s reference to the Roman portrait tradition, Rockwell makes it clear that there is no family resemblance between the deliveryman and his charges.

* https://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1528.html

** In the 1920s and early 30s business or everyday shirts were either striped or white; dress shirts were always white; and work shirts were darker tones ( black, khaki, dark blue, or gray) that did not easily show dirt. See, Fredonia Jane Ringo, Men’s and boys’ clothing and furnishings (Chicago, New York: A. W. Shaw Company: 1925): 49.

*** Spat is the abbreviated form for the word spatterdash which describes a short cloth or leather gaiter.

November 4, 2010

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

Norman Rockwell Museum