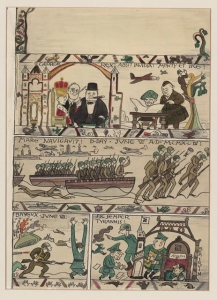

Rea S. Irvin (1881-1972)|D-Day Invasion of France, 1944|Cover illustration for New Yorker magazine (July 15, 1944)|Ink and watercolor|Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs, LOT 9329

This New Yorker cover illustration was published on July 15, 1944 to commemorate the Allied armies D-Day invasion of Normandy. It was created by Rea S. Irvin, the art editor of the magazine, who also created many of the weekly’s covers during his long tenure at the magazine. Early in the morning of June 6, 1944, the Allied forces assaulted the coast of Normandy, France in two phases: the first was the airborne invasion that landed troops and the second was an amphibious landing of Allied infantry and armored divisions along a 50-mile stretch on the coast of France.

Irvin’s New Yorker cover about the D-Day invasion is constructed upon various scenes from the Bayeux Tapestry, c. 1077, a 20-inch tall and 230-foot long continuous strip of embroidery decorated linen describing in pictures and Latin words, scenes that led up to the Norman invasion of England and the Battle at Hastings in 1066.* The borders of this historical and artistic document are filled with mythological figures, scenes of farming and hunting, and scenes from Æsops fables.

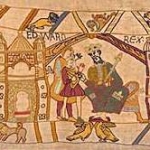

In this first scene of the Bayeux Tapestry (seen here), it is 1064 and in the Royal Palace of Westminster, Edward the Confessor, King of England is talking to his brother-in-law Harold, Earl of Wessex. On the New Yorker cover, in the same rubric for a castle are seen King George of England being told about the invasion plans by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. The second panel at the top of the cover shows the Allied Expeditionary Force Supreme Commander, Dwight D. Eisenhower (Ike) and the British General Bernard Montgomery (Monty) looking over the invasion plans. The border sections of Irvin’s cover are also symbolic. Under the top panels are images of a hand holding the torch of liberty, a radio announcer informing people of what’s going on, two hands clasped, and a bird, perhaps an American eagle.

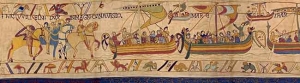

The middle scenes of the New Yorker cover show the arrival of the troops via airplanes and amphibious squads coming ashore. The Allied operation had its glitches which Irvin indicates by showing a soldier swimming ashore on the left and on the right, one soldier carrying another on his back. Like the original comparable scene in the Bayeux Tapestry, which is named “Mare,” or “the sea,” the title for this section of Irvin’s version reads, “Mare Navigavat : D-Day June VI, MCMXLVI. The decorative border below these middle scenes of the arrival of the Allied troops are decorated with fish and what appears to be an aircraft carrier.

The bottom left scene of the magazine cover, notated as “Bayeux June VII,” shows Allied tanks moving through the landscape while the Allied infantry routs the German infantry. Again, not everything is wonderful, as Irvin shows the legs of a fallen soldier at the left. The border below this portion of the lower panel shows other hands raised in surrender.

In the last panel of Irvin’s cover illustrate the battle with a puff of smoke coming from the left and a soldier running away to the right. To the far right of the scene is another castle rubric lifted from the Bayeux Tapestry, holding the new King, Harold. In the modern version, Irvin tops the left tower with a swastika on a flag so that we would know that this is Nazi headquarters, instead of the comet in the sky above the castle as in the original tapestry. Inside the castle, hiding under the bed, is a caricature of Adolf Hitler. He is accompanied by his private secretary, Martin Bormann. Outside, holding on to the tower appears to be a caricature of Heinrich Himmler. The other officer outside of Hitler’s accommodations, might be a caricature of Erwin Rommel, who commanded the German forces opposing the Allied cross-channel invasion in Normandy. The Latin phrase that describes this scene is “Sic Semper Tyrannis,” which translates as “thus always to tyrants.” The border of final right hand scene is decorated with rats running away.

By using the Bayeux Tapestry as the model for his New Yorker cover, Rea Irvin not only brought historical gravitas to his image, he used the same sort of compression of scenes and parenthetical images to tell a complex story in a minimum of space.

* You can see an illustrated version of the Bayeux Tapestry on YouTube.

June 4, 2010

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, The Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies

at the Norman Rockwell Museum