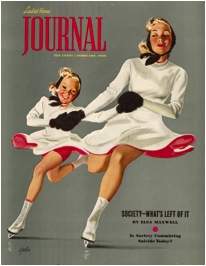

- Alfred Charles Parker (1906-1985)|Mother and Daughter Skating, 1939|Cover tear sheet for Ladies’ Home Journal (February 1939)|Al Parker Collection, Dept. of Special Col., Washington University Libraries © by the Meredith Corporation

Certain topics transcend generations in their ability to spark interest and debate. The dynamic of the mother-daughter relationship is one such subject. Currently, the cable giant HBO is premiering its newest miniseries, Mildred Pierce. Adapted from the 1941 novel by James M. Cain, Mildred Pierce casts a class-centric look at the complex bond between mothers and their daughters. While Cain’s novel already received a cinematic reimagining with the iconic 1945 film starring Joan Crawford, HBO’s newest iteration affirms our continued cultural fascination with this dynamic.

In the years surrounding the publication of Cain’s novel and the release of its first film adaptation, St. Louis-born illustrator Al Parker similarly began to explore the mother-daughter relationship. From 1939 through 1952 the Ladies’ Home Journal ran what would become a series of over thirty Mother-Daughter cover illustrations created by Parker.* Featuring a flaxen-haired mother-daughter duo participating in a range of activities, from swimming to baking, these covers chronicled both the fictional lives of their two figures and a nation shaken by foreign conflicts, particularly World War II.

In their depiction of a mother and her daughter, who appears as a miniaturized self, Parker’s images present an ostensibly idealized rapport. In truth, Parker’s visualization of the bond shared between the two reflects a profound intimacy, one that is at once physical and psychological.

Physically, Parker’s mother-daughter duo shares a powerful resemblance. The inaugural cover, appearing in February 1939, provides but one example of this series-long phenomenon. Shown ice-skating, mother and daughter appear equally endowed with shiny blonde hair, fair skin, and rosy cheeks. Moreover, each figure sports matching white skating dresses with pink underlay, fluffy black gloves, and corresponding black headscarves.

Compounding their physical similarities are the duo’s parallel movements. Gliding across the invisible ice, both figures lean to their left sides, anchoring their respective left legs to the ground while curving their right legs behind them in motion. In their parallel movements, even their blonde coiffures and swinging skirts blow in the same direction.

Mother and daughter physically adjoin one another, as well. Clutching each other’s hands, their limbs interlace. Parker so hazily renders their matching black gloves, serving as the locus of their physical contact, that one cannot distinguish where the mother’s hands end and her daughter’ begin. This fusion of their forms increases at the level of their skating skirts. Swishing against one another, the skirts’ hems are ill-defined and the snowy whiteness of each blends together to form a unified garment. Finally, the young girl’s backward-swinging right foot moves so close to her mother’s bent knee that the two limbs morph together into an apparently single appendage.

On August 13, 1949, the Ladies’ Home Journal released a promotional poster featuring thirty of Parker’s Mother-Daughter covers, beginning with his February 1939 ice-skating image. As Parker continued to create new Mother-Daughter covers after 1949, with the latest known to date from 1952, we can conclude that the series at least numbers thirty-one images.

Combined, Parker’s compositional details move beyond establishing a physical connection. These characteristics serve as visual manifestations of the interrelatedness of the pair’s psychological selves. The strength of their physical bonds, variously expressed, clearly positions them as a mother and her daughter. Furthermore, the two figures appear less as autonomous individuals than as members of a larger whole: the mother-daughter unit.**

While highlighting its closeness, Parker’s covers also hint at darker undercurrents present in the unit. Suggestions of conflict are particularly evident when the Parker introduces audiences to the duo’s husband/father, a figure who remains largely faceless and mostly absent throughout the series. The series final cover, dated May 1952, shows mother and daughter, poses mirroring one another, kissing the husband/father’s cheeks upon his return from service in the Korean War. They are joined by a gleeful younger son/brother, whose birth coincided with the husband/father’s initial post-World War II homecoming. In this composition, Parker sets up a more confrontational dynamic between mother and daughter, who nonetheless remain united by their shared resemblance. With faces pitted against one another, the two females seemingly compete for the attention of the father, who divides their once-conjoined figures. Lips puckered in a slightly exaggerated manner and eyelashes’ fluttering girlishly, the daughter serves as the innocent and naïve counterpart to her mother, whose vermillion lipstick and deeper kissing gesture render her more mature and sexualized. However, the reflective quality of their poses suggests that the daughter is but a younger version of her mother and will, subsequently, “become” and, perhaps more ominously, replace her. Showcasing a relationship defined by closeness yet hinting at conflict and separation, Parker’s Mother-Daughter cover series proves as complex as the relationship it illustrates.

* My exploration of the unitary mother-daughter dynamic in Parker’s images is greatly informed by psychoanalytic theory emerging during the 1930’s and 1940’s. Sigmund Freud’s 1931 essay “Female Sexuality” outlines the concept of the pre-Oedipal phase, a period in female childhood defined by close attachment to the mother. In The Psychology of Women, a two-volume series dating from 1943 and 1945, psychoanalyst Helene Deutsch further explores the pre-Oedipal phase, its relationship to the developmental stage of pre-puberty, and the mother-daughter closeness that characterizes them both.

** On August 13, 1949, the Ladies’ Home Journal released a promotional poster featuring thirty of Parker’s Mother-Daughter covers, beginning with his February 1939 ice-skating image. As Parker continued to create new Mother-Daughter covers after 1949, with the latest known to date from 1952, we can conclude that the series at least numbers thirty-one images.

May 5, 2011

By Emma Dent, graduated student of the Department of Art History & Archaeology, Washington University in St. Louis