Nina Allender (1872-1957)

Nina Allender (1872-1957)

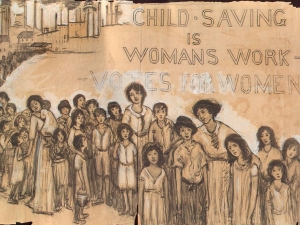

Child-Saving is Womans Work, 1914)

Cartoon published in The Suggratist (July 25, 1914))

Sewall-Belmont House & Museum, Washington, D.C.

Trained as a painter at the Corcoran School of Art and at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, in 1913 Nina Allender turned her art talent to support women’s suffrage.* At the request of Alice Paul, the founder of the National Woman’s Party, Allender became the party’s official cartoonist. From 1914 through 1927 she created hundreds of editorial cartoons focused on the suffragist cause. Many of these cartoons were published on the covers of The Suffragist or its successor publication, Equal Rights, weekly newspapers of the organization.

The above illustration, Child-Saving is Womans Work, reflects one of the avenues of interest in the women’s movement political agenda–the need for protective labor legislation for child workers. To visually make her point, Allender drew a stream of thin, poorly clothed children winding away from an industrial cityscape in the far left background of the image. In the blank paper on the right, Allender lettered in the tag-line: child-saving is woman’s work—if America women had the vote, they could turn their political power to help the children they embrace as they leave their factory jobs.**

In the right foreground three woman stand among the children and each of them has gathered in some of the children into the shelter of their arms. These women, especially the one holding a child in her arms visually reference images of the Madonna usually portrayed hold the Child Jesus. The women with their arms outstretched around the children reference another type of the Madonna—one called the Madonna della Misericordia—a version of The Virgin Mary who shelters and protects people under the fabric of her cloak. She was a popular devotional image from the 13th through the 16th centuries and is described as a Madonna of Mercy. Allender’s use of a similar compositional element makes her images of women the suffragist’s women of mercy.

Piero della Francesca (c.1415-1492)

Madonna della Misericordia, 1445-62

Segment of an altarpiece for Sandepolcro, Florence

Oil and tempra on panel

Pinacoteca Comunale, Sansepolcro

The real point was that while children were traditionally part of the rural family’s work force, in the wake of the industrial revolution, they were employed by various industries so that they might contribute to their poor family’s income. Factories and mines utilized (and exploited) child labor because they were less expensive to pay and because their smaller bodies might more easily fit into tight spaces or their nimble small fingers could keep the textile mills’ bobbins untangles or roll cigarettes. Even before Allender’s cartoon, photographer Lewis Hine was capturing images of child laborers as a staff photographer for the National Child Labor Committee (see below).

Lewis Hine (1874-1940 )

Nannie, a young “looper” in a hosiery mill, c. 1908-12

Photograph

New York Public Library, Photography Collection

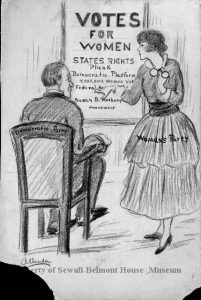

Beyond representing women’s political point of view regarding their rights and obligations, Allender provided an image of the American suffragist in contrast to how they were portrayed by male cartoonists who tended to focus on images of unattractive or scolding females. The “Allender Girl,” was a slim, attractive, attractively dressed, engaging, and compassionate young woman. Even when her purpose was to scold male Americans and male dominated American institutions, it was done with a gentle touch and a whiff of humor. For example, in the cartoon below, a pretty young thing labeled ‘Womans Party’ with eye glasses in hand, points out to the Democratic Party, in the guise of a man seated in an arm chair (as though he has trouble seeing) that the votes of 4 million women might be brought to bear on other issues if the Democrats supported the Susan B. Anthony Amendment.

Besides making important political points, Allender’s political cartoons remind us of the axiom, ‘You can catch more flies with honey than you can with vinegar.’

*Allender also studied in London with Frank Brangwyn. I thank Dr. Michael Lobel for introducing me to the collection of the work of Nina Allender at the Sewall-Belmont House Museum in Washington, DC.

** The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 included the prohibition of most employment of minors in “oppressive child labor,” while it also limited the maximum hours of a seven-day work week (44), and established a national minimum wage.

July 25, 2013

By Joyce K. Schiller, Curator, Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, Norman Rockwell Museum