Episode 08: Bob Eggleton (Part 1)

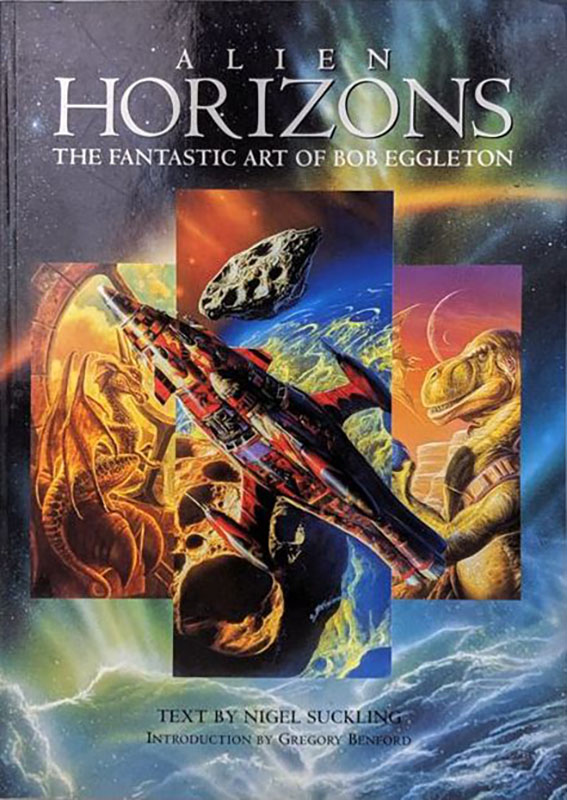

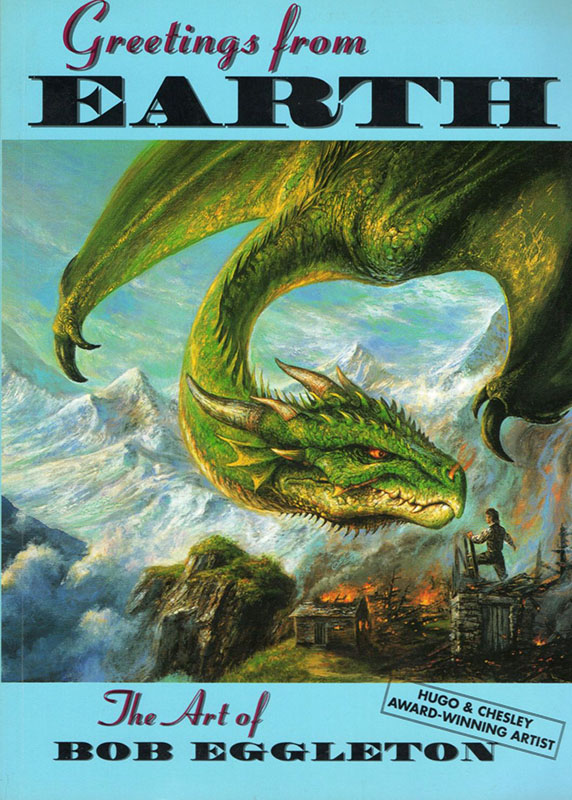

Jesse Kowalski: Welcome to The Illustrator’s Studio. I am Jesse Kowalski, Curator of Exhibitions at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. The Illustrator’s Studio is a weekly interview series, a project of the Museum’s Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies. This interview with Bob Eggleton is the first of a two-part interview on his life and career. The second part will air next week. Today is a special treat as I get to speak with one of the masters of fantasy and science fiction illustration, Bob Eggleton. Eggleton has illustrated and written numerous books on fantasy and sci-fi. And between 1994 and 2004, won the prestigious Hugo Award for Best Professional Artist, eight times, and was nominated an astounding 31 times. His art has been showcased in the 1995 book Alien Horizons: The Fantastic Art of Bob Eggleton. And the 2000 volume, Greetings from Earth: The Art of Bob Eggleton.

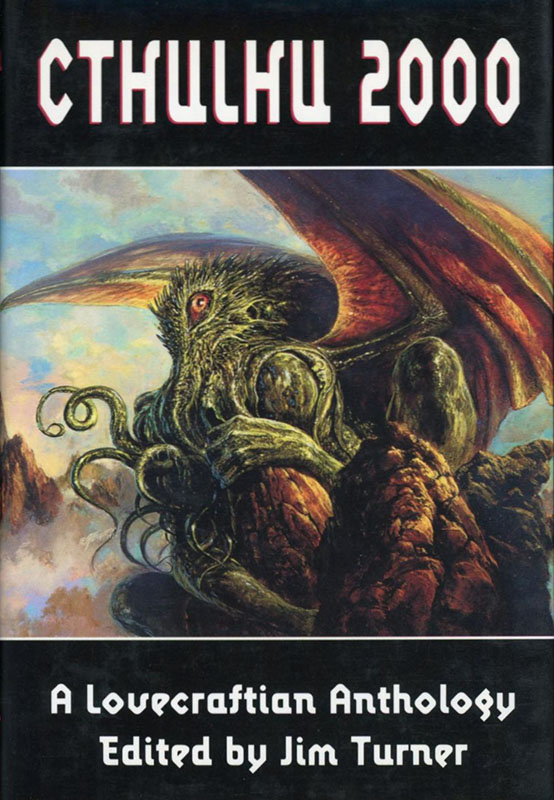

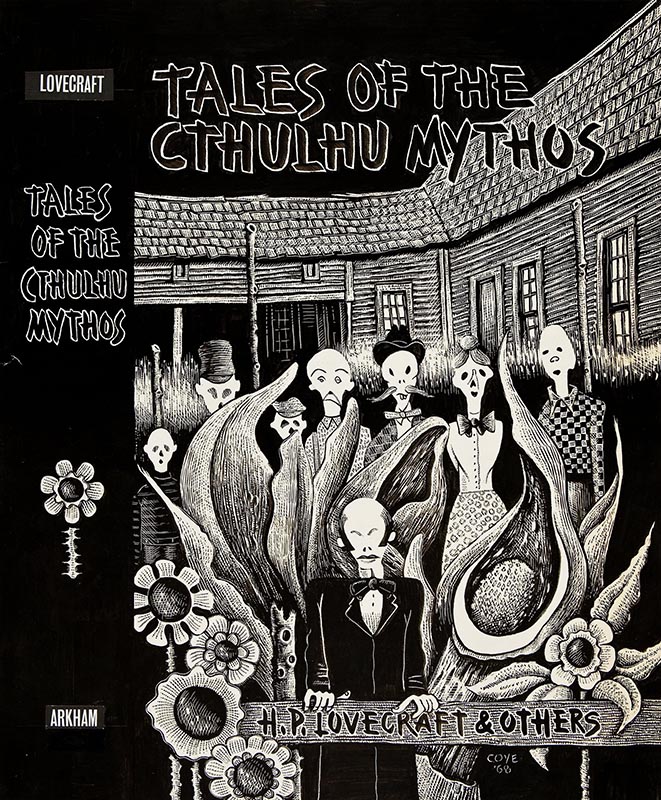

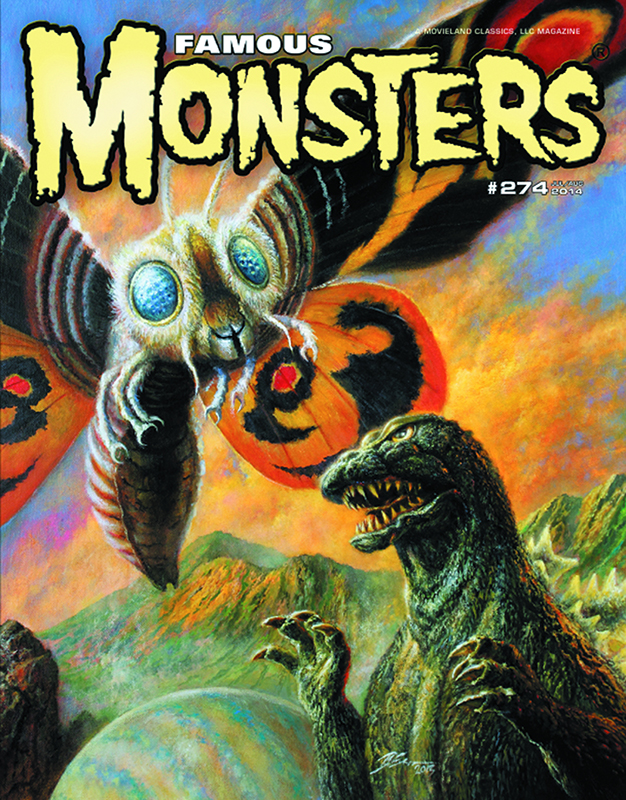

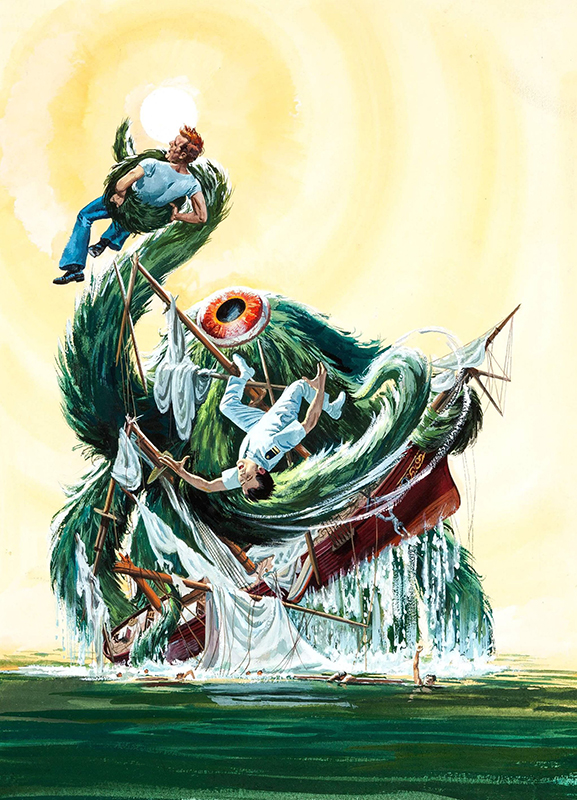

In 1995, Eggleton painted the cover for the Lovecraft inspired, Cthulhu 2000: A Lovecraftian Anthology, a collection of stories by 18 horror and fantasy authors. His work brings to mind legendary illustrators from the past, whom I will mention in a moment. As with many fans of his, I came to know Eggleton’s work through his paintings of Godzilla and characters from the stories by H.P Lovecraft. Eggleton’s masterful brushstroke brings new life to established kaiju and ancient gods. In fact, he painted a stunning image of Lovecraft’s Cthulhu for the Enchanted exhibition opening this June, at Norman Rockwell Museum. I am thrilled to speak with him today. Welcome Bob.

Bob Eggleton: Hey, how are ya?

Jesse Kowalski: Good. How are you doing?

Bob Eggleton: Good, good, good.

Jesse Kowalski: So yeah, I wanted to start off with some of your influences. I can see the influence of a number of artists in your work. I wanted to run through some of the artists and get your input on the impact that they’ve had on your career, if any, or just

Bob Eggleton: Sure. I can probably add to it too, some artists.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah. So how about the English artist, John Martin?

Bob Eggleton: Oh my God. Yeah. I flew to England just to see a special exhibit of his work in 2011. The Tate Gallery did this huge retrospective of his stuff, and they put out a catalog with… He hasn’t been widely seen in a lot of art books made of him and things of that nature. So when they did this exhibition, I was just there and they actually restored a painting that had sat since 1928, completely damaged. The middle was missing out of it. And they had a restorative artist go in and she redid this entire scene. And they did it with computer targeting and pinpoints where the lighting would go and all those kinds of stuff. And it’s Mount Vesuvius erupting, and you can see where it’s been restored and it just was a fabulous piece to see.

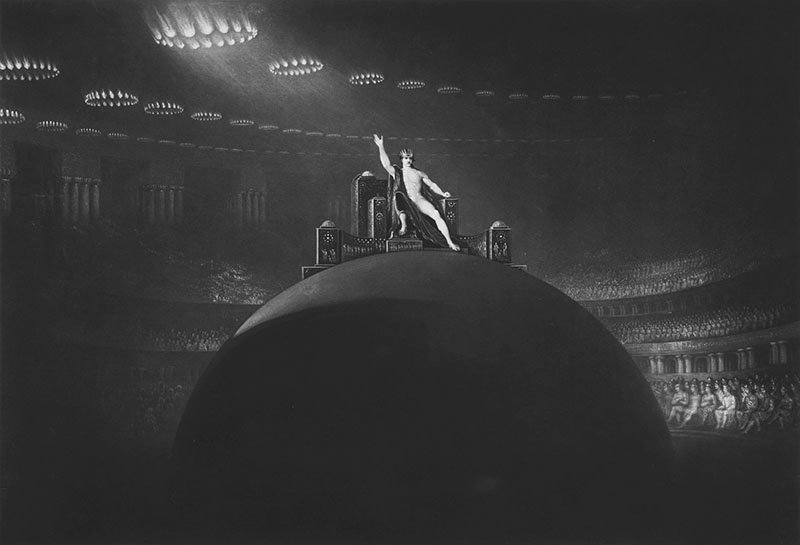

So they unveiled it there at that show, because nobody had ever seen it. It was kind of lost work. I love his epics. He was kind of an outcast pastor of some kind, I guess. He did these epics that resonate now as they do then. I mean, The Great Day of His Wrath, which is this incredible painting of the earth being turned inside out by God and all of the false prophets and the money being sucked into this huge abyss. And it’s a fabulous… An amazing painting. He’s got another one of a dragon and he’s got another one of… It’s all of it. When you really look at it, it’s all fantasy artwork. It’s just, they didn’t call it that then. They called it sublime or they called it symbolist or they called it allegorical, that sort of thing. They never said… Or romantic, that’s the big word they used. Romantic. And they wouldn’t say fantasy, because I don’t think anybody thought that at the time.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah. We’ll have one of his engravings in the exhibit from Paradise Lost – Satan in Council.

Bob Eggleton: Yeah. He did some amazing work and his paintings are just epic. I mean, they are just every bit as epic when you see them up close. He’s a major influence to me, as Gustave Doré is, he’s another one. And Gustave Doré was an influence of Frank Frazetta. And Frank Frazetta doesn’t really talk about that too much… didn’t talk about it too much at the time, but his favorite, when you would pin him down, his favorite artist was Gustave Doré.

Jesse Kowalski: Okay. Another artist, José Segrelles.

Bob Eggleton: Yes. He’s amazing. Pretty amazing stuff. Segrelles, I think there was a father and son, wasn’t there? It was a two… I know one Segrelles did a lot of Daw book covers in the 1970s, and then he did this dragon graphic novel thing that’s all painted in oils and it’s just really, really… That’s Vicente Segrelles. That’s it. Vicente Segrelles. And I think it’s a father and son kind of thing, or grandson or something like that. But anyway, he did that. And so I’m very familiar. They have very similar styles, but it’s fantastic stuff.

Jesse Kowalski: I was thinking, one of your paintings in particular looked like a Segrelles work from War of the Worlds.

Bob Eggleton: Right. Yeah.

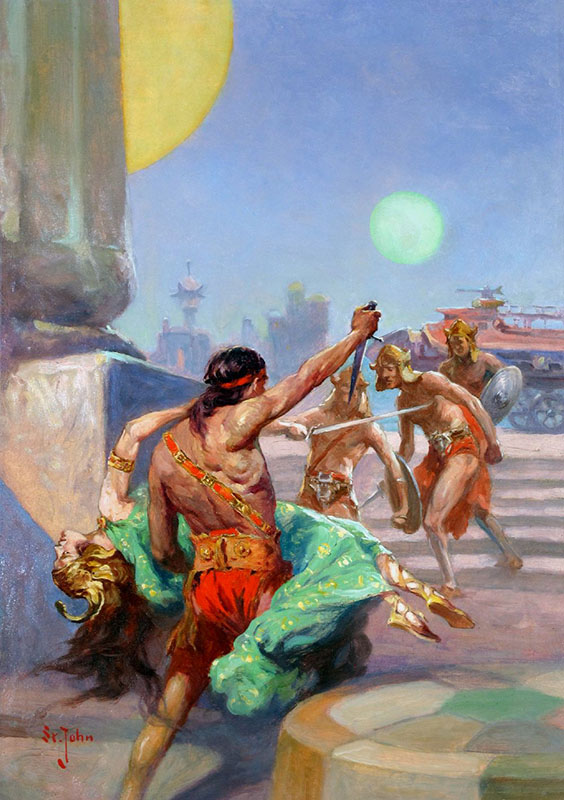

Jesse Kowalski: Another artist, J. Allen St. John.

Bob Eggleton: Oh my God. Yeah. J. Allen St. John, he’s like the ultimate illustrator of Edgar Rice Burroughs, John Carter of Mars. I mean, he was… All respect to everybody who has illustrated him since. J. Allen St. John really had that look to everything. He had that real… He really captured some romantic stuff and some incredible imagery. And the way he did dinosaurs and prehistoric monsters and things of that nature, it was just… He really made them… It was ‘30s kind of science that we knew, but that’s what he had to work with. But that’s why there’s a charm in them, and it’s really terrific to see it.

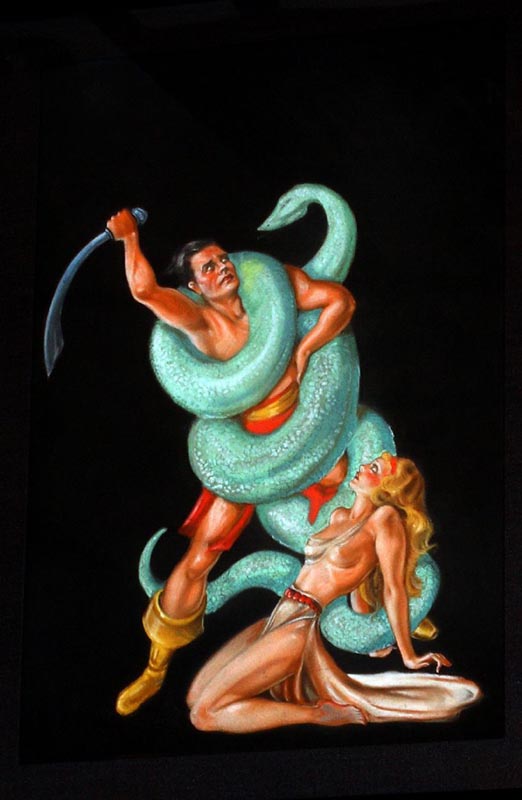

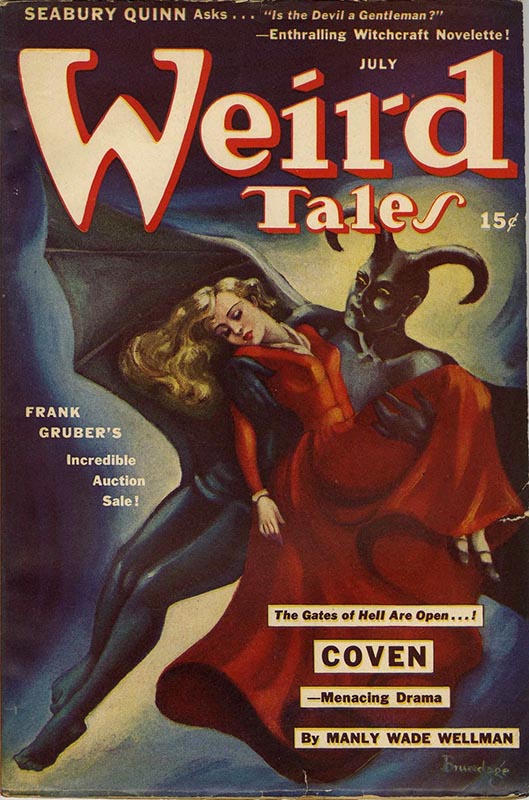

Jesse Kowalski: And how about pulp artist, Margaret Brundage?

Bob Eggleton: Yes. Margaret Brundage, very nice stuff. I’m a big fan of a lot of the pulp artists. A lot of them that… Hubert Rogers, he’s another one. There was a sort of a garishness, but also a simplicity to the work that was really attractive to me. And I really liked the use of a lot of icons of fantasy and science fiction in them, that were just very… They really got to the core of it. I mean, Rogers put in rocket ships. He put in rocket ships and stuff like that. And there was something about that, that was really nice.

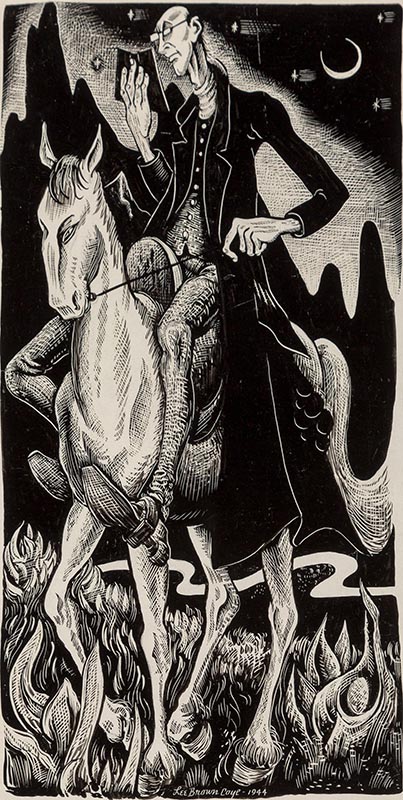

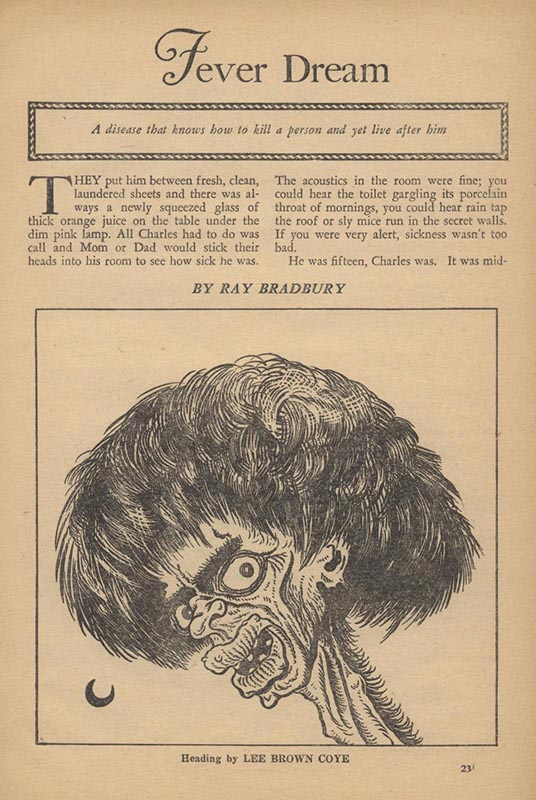

Jesse Kowalski: And Lovecraft illustrator, Lee Brown Coye?

Bob Eggleton: Oh yeah. Well yeah, really nice stuff. Really beautiful. Kind of a minimalist, but I really liked that kind of… That it left more to your imagination. That’s what I like about sort of the more looser and impressionistic artists. It leaves a lot to your imagination, to look at it. And you can make up things you see within it. Another influence to me, a big one for me, was Turner. J.M.W Turner. His lighting and his implied details of things, were incredible. As he got older, dementia and his eyesight went. Basically, dementia set in and his eyesight went and all kinds of stuff. He had lead poisoning, is what I understand it. And his stuff got very filmy and weird, and it was still really great, was still really great. But he’s a big one. He’s done some fantasy, Apollo and the Python is a great one. There’s another one of slaying a dragon, which you can barely see the dragon, but it’s there. And it’s just implied. It’s very implied in there.

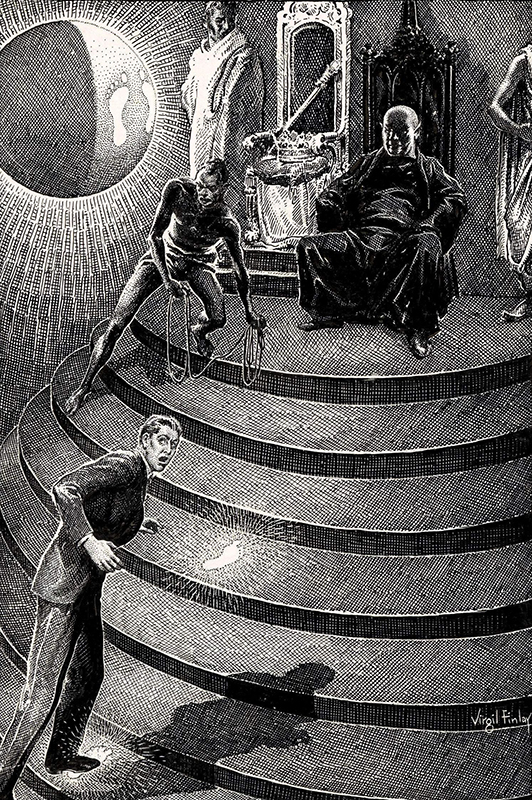

Jesse Kowalski: Okay. Another artist, Virgil Finlay.

Bob Eggleton: Yes. Virgil Finlay, beautiful. Not many people knew… They always lauded him for his pointillist and his scratchboard and ink techniques and things like that, but they never really realized he was also a painter, too. And he did very few paintings, but the ones he did, were really, really spectacular.

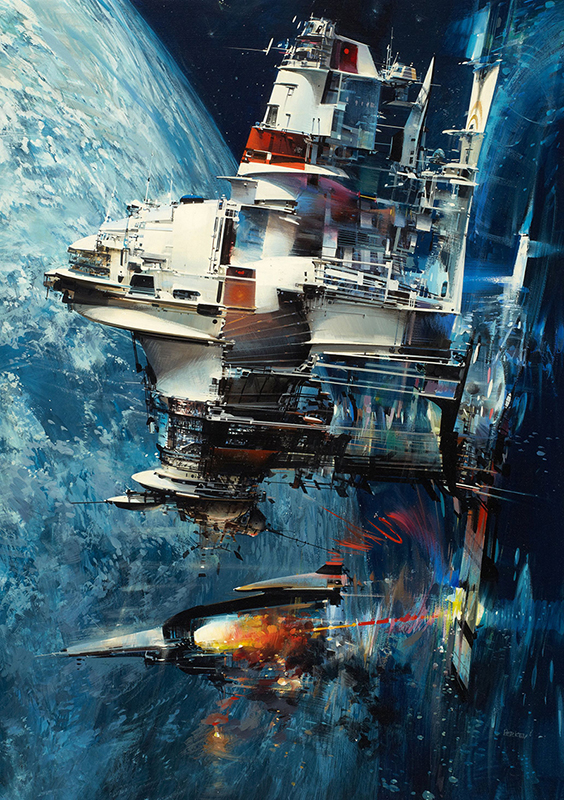

Jesse Kowalski: And the last one I’ll ask you about is John Berkey.

Bob Eggleton: Oh yeah, John Berkey. He kind of invented the spaceship pile made of junk, as it were, before it all became very popular. And that’s where it sort of became a concept art stuff. And Berkey had an incredible output of work, especially in the ‘70s. He was a big movie poster artist. He did things like… He did a movie poster for a thing called The Neptune Factor, which is an awful film. It’s a terrible movie. It’s got those special effects, something like an aquarium. It looks terrible, but the poster made it look like this epic monster movie. And it was great. And the poster was the best thing about it. And he did the art for King Kong, the 1976 King Kong.

And what had happened was, is that he did the initial poster. And back then, they worked with telex machines. They didn’t have fax or internet. They were telex. And he did this scribbled-out idea of what it was, and they said, “We’ll do that.” And they did this painting and they got the announcement poster, as it were. And then later on, Dino de Laurentiis came along and said he needed ten more paintings done to help promote the movie. Because what was happening was, they didn’t want to show… It was highly touted, if you remember at the time, it was going to be this big robot, full-size Kong that was made by Carlo Rambaldi. And all it really did for ten seconds, is raise its hands like that. And then that’s all you see in the movie. And the rest of it is Rick Baker in a really good ape suit. But they didn’t want to say that. They didn’t want to promote that. They wanted to say it was this giant robot thing.

And what had happened was, Dino, what he did, rather than release photos of Rick Baker in the ape suit, was that he had John Berkey paint these eight or ten paintings. I forgot what it was. Anyway, John had something like two and a half weeks to do them in. And when he was done, he was hospitalized with pneumonia because he got so sick from not getting any rest. And he got them done. But he had a way of painting in mirrors. He never looked at his work, looking at it. He would look at a mirror as he was paint… Kind of a strange mirror system, where he would look at it in reverse as he was painting.

And that way, he claimed that you get a lot more balance going on and things of that nature. But he was so iconic. He did a poster, The Towering Inferno. He did a ton of movie posters that you didn’t even think that he did, because they look photographic. Because they were done so big, they were gigantic, and he did them. And then he sort of segued into things like some book covers and everything like that, in the 1980s. And basically, all the stress of it, it gave him a heart condition that he eventually passed away from. But it was a really… He was just an absolutely amazing artist that contributed so much to science fiction.

And I consider him very underrated in the community of science fiction, not in illustration. Illustration, he’s a God. But in the community of science fiction, nobody thinks of John Berkey. Nobody says… you know, John Berkey did 250 covers or something like that. I don’t even think he got a Hugo nomination or anything. Maybe one. I don’t know. I don’t think it was very many. But he did so much mainstream art, that the science fiction art was kind of a side thing.

Jesse Kowalski: Are there any illustrators I missed?

Bob Eggleton: Oh, I mean, I could name 100 more artists that I like. Everybody I see, I get so inspired by their work. I mean, a lot of the great… I go back to a lot of the classical artists to get my style. It was kind of nice, because I tell a lot of younger artists, “Don’t start copying somebody who’s hot right now. Go back to what these guys got inspired by. Don’t be another Frank Frazetta. You never will be. Go back to what these guys were inspired by and start your own style from that.” And that’s what… I mean, Ray Harryhausen was inspired by Gustave Doré. These great jungly scenes that he did and etchings that were just incredible. And the original King Kong movie was inspired by that, so.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah. It seems that Norman Rockwell, in the beginning of his career, copied a lot of Leyendecker’s work until he really developed his own style, like you said, based on illustrators from the past.

Bob Eggleton: Yeah, exactly. And something about Rockwell’s work was so storytelling. You could just stare at it and it would just tell the story right there, and that’s what… In one look. One look would do it. And that’s the marvelousness of his work.

Jesse Kowalski: I categorize your images generally as weird fantasy, but how do you define the genre of fantasy illustration in your work?

Bob Eggleton: I kind of say, weird fantasy. I do dragons and things of that nature, but there’s always an edge to them. I’m not one for doing the more lighthearted stuff. I’ve tried it, but I’m not sure it’s in my psyche to do that. And there’s other artists that do it better than I, so it’s just not something that I do. But the idea, the concept of showing these dark images, it goes back to mythology for me. It’s sort of a mythological thing. If you’re into the concepts of… You look at these great tales, The Odyssey. Homer’s The Odyssey. I mean, they had monsters in it, you know what I mean?

And so you have all those things and everything’s so left up to interpretation. And the Japanese have these incredible stories of the beast of Yamato, they’re called. And it was this seven headed giant dragon they have. And then the Yokai. Yokai, which are the Japanese ghosts. And one of those little guys is called a Kappa, and he’s this really… You just research him, and he’s just this little mischievous ghost. And then he has a plate of pickles on his head or something like that. And they live in the water and they live… And Daiei Pictures, back in 1966 or seven, they made these series called Yokai Spook War. And it was these three movies that are rarely seen in the United States, and they are absolutely the weirdest thing you will ever see in your life. And this is all done with these practical effects, and it’s just people being… Like an umbrella with a tongue and one eye on it. I mean, it’s really strange stuff. And you think about it, you think it looks silly, but the way they film it, it’s scary as hell. It really is.

And when you go back to those great myths of that, you look at that, the Chinese, the Asian dragon that represents great wisdom. And it’s ornate and very… I got one right here, actually. It’s very ornate and very colorful and stuff, and it battles… There was kind of encounters with a being called, Wukong, or known as the Monkey King. And that’s another great story. And it’s this great mythology, and it’s very Asian. And all of this stuff works forward to feed my imagination to what I do. Because you wonder, this is where it all comes from. This is where the beasts… This is where Godzilla originated from, was these myths of giant beasts. All of it was like that.

So that’s why I like… And H.P Lovecraft, when he did his monsters, he determined that his monsters were these badly… Well, people saw them as ghosts, so to speak, or demons. But he determined that they were the creature’s bad astrology, as he called them. They were creatures from another realm that came through – the Old Ones. And they came from a planet far, far out in the solar system. And they came here on leathered wings and things of that nature. And basically, you had this concept of it’s kind of a mythology and it turns into, later on, people thinking it’s ghosts and poltergeists and things like that.

Jesse Kowalski: Let’s travel back in time for a moment, to imagine a young Bob Eggleton. What is this kid doing? What kind of movies, TV shows, or books is he watching?

Bob Eggleton: Well, how young? So, we’re going back to how young?

Jesse Kowalski: Oh, let’s say ten to seventeen.

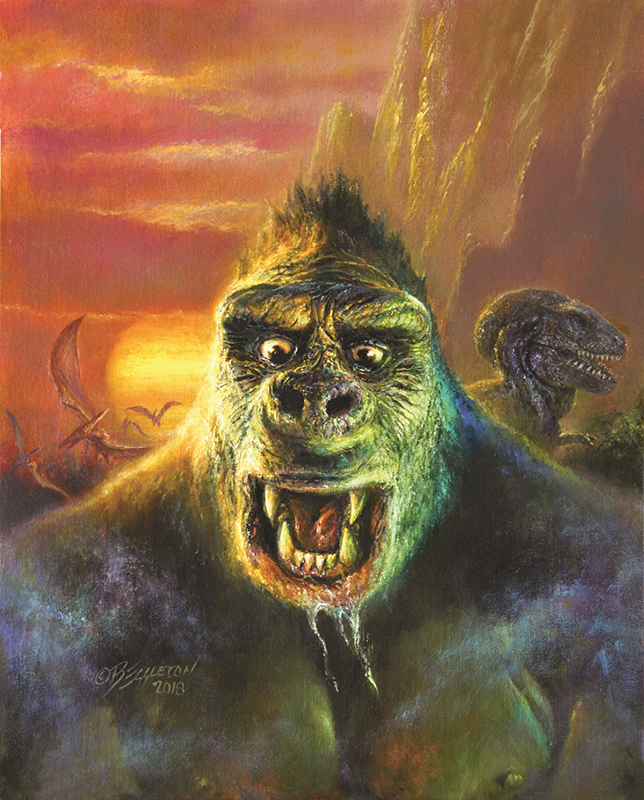

Bob Eggleton: Oh boy. Well, at nine, I can tell you a funny story. I was taken to see the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, which is one of my favorite movies. It really is. My favorite science fiction movie. And I was sitting in there, in the theater, and my mother was with me and some other people who had come along. And they said, “Well, if you don’t understand this film, just talk to us about it afterwards and maybe we can help you kind of understand it.” Well, guess who explained it to them? You know what I mean? And I was nine. And so my whole thing was Famous Monsters of Filmland, which I got to later on in life. Thirty-five years later, got to do the covers to Famous Monsters of Filmland.

There was comic books, there were movies. And we didn’t have DVDs or VHS or any of that kind of stuff, so we had this little mom and pop theater down the street where I used to live. And it’s gone now, but they would show all kinds of dinosaur and monster movies on weekends and things of that nature. So it was really, all of that was fuel for the fire. And I’d come home and draw them on paper and stuff like that nature. And that’s sort of when I was really formulating ideas in my head of what I really liked. And some people worry, they said, “Oh, he’s into these monsters. It’s kind of dark and scary.” And all that stuff. Well, the monsters for me, was something I identified with because monsters are so misunderstood. The Frankenstein monster. Boris Karloff in the first two Frankenstein films, he plays such a misunderstood, tragic figure.

And he’s trapped in a world he never made, and he stuck with it. And it’s the same with any of these monsters. Godzilla, Creature from the Black Lagoon, any of them, they all came from this time when there was a…. They were unearthed by man, so to speak. They were brought into the world in some way, they were left on their own. The Creature from the Black Lagoon, he was left on his own, he was fine. And then man goes to hunt for him and he becomes hostile and he fights back at them. You know what I mean? So it’s not really his fault, it’s their fault for coming to his world and that sort of thing.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah, no. I’ve read that, that’s why a lot of kids identify with those characters, is because they do sympathize with the ways they’re misunderstood and things.

Bob Eggleton: Right. Exactly. Absolutely. It’s amazing. And when you see this thing… I mean, Godzilla started off as nuclear horror that was inspired by, believe it or not, King Kong. Tomoyuki Tanaka, who was the head of Toho pictures at the time, they played King Kong in Japan and it did very, very well. And then they played The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, which did very, very well.

So they came up with the idea of this giant sea creature that first was envisioned as an octopus. It was going to come up out of the water. Well, an octopus became technically a problem to film. So they made it into a dinosaur-like creature, and thus Godzilla was born. And he was such a popular hit, that through the ages, as Japan changed and Japan became a more industrialized nation… Post-war, they became very industrialized, very commercialized. The directors of the films started putting these… The director, Ishiro Honda, started putting in a political angle to it, about showing that… Especially in King Kong vs. Godzilla, and then Mothra vs. Godzilla, that there was money hungry people that wanted to make money off these monsters. And then of course, they wind up meeting their own ends badly because of that.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah. There’s a great one. I don’t remember the name of it, but it’s about pollution…?

Bob Eggleton: Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster, Hedorah.

Jesse Kowalski: There you go. Yeah. That’s a great one. So were there other things, or people that inspired you growing up?

Bob Eggleton: Yeah. I mean, my dad was great. He sat me down and he… When I was sick, when I was very young, and this is way back, he would sit me down and we would do drawings on a big chalkboard. And he showed me how to do perspective and he was kind of an all around guy. He was an inventor, he did architecture, he did drawings and blueprints and architecture and all that kind of stuff. And he showed me how perspective kind of works and we did it. Because I was very ill when I was young, and he said that it was something that… He put it into me about using a lot of common sense and stuff like that. He was a good guy.

Jesse Kowalski: Did you always know that you wanted to paint for a living?

Bob Eggleton: Well, draw. I used to buy comic books and at one point, I was so young and had this naive idea that every single comic was drawn for me. And of course, that wasn’t the case. And what I did was, I did… I loved all the old Jack Kirby comic books from Marvel Comics. And back when a dollar could buy you five comics. And the painting that got interest in me, was an artist named George Wilson, who was an illustrator. And he did the covers to a thing called, Boris Karloff Tales of Mystery. And it was a Gold Key comic. And he did all the Gold… Gold Key was the only comic company that they sprang out of Dell Comics. They’re the only ones that had painted covers. Marvel Comics wasn’t doing that quite yet. And they did Marvel Magazines, which got into that. But Gold Key actually had these painted covers and they had monsters on them and they were just incredible. I mean, there it was. I mean, I’m going, that’s what I want to do. And so I was about eleven when I made that decision. Yeah.

Jesse Kowalski: So you studied at art school for, I think about eighteen months before dropping out.

Bob Eggleton: Yeah. It’s a long story about that. Okay, let’s go back to 1978. And I was looking at art schools… And I got a good story about a teacher, too. What had happened was, I went to Rhode Island School of Design, had taken a tour of the place and all that. And they were just in this time of, let’s call it post-Vietnam, post-Watergate. That whole kind of time in the ‘70s when everybody was just really… They were kind of really laid back. And then everybody was deciding that realistic art really was… Representational art was a thing of the past. They were deciding, well why do that, when you can put a pile of dirt in the middle of a room and stick two shovels in it, and that’s your comment on society.

And that’s what was happening to a lot of schools. They weren’t teaching, that I saw, and this is… Again, this is 1978. That I saw, they weren’t doing the basic drawing. They weren’t doing the basic… The real basic skills that you need, like drawing and all that. It was a very different time. And what had happened was, my parents said, “Do you want to go to RISD?” And mind you, at the time, it was five or $6,000 a year. I mean, that’s nothing now. Anyways. So I said, “You know what? I really want you to save your money.” And so instead, I went to Rhode Island College because I went up there, and their art department was all RISD teachers. So I said, okay, I can do that for $600 a year.

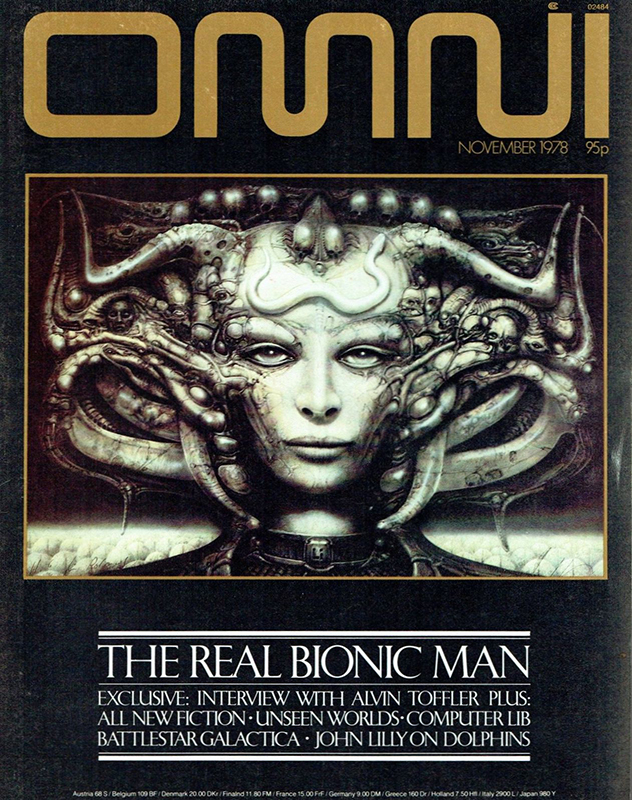

So I went up there and the guy that I really met that really, really had a profound influence on me, a massive influence on me, and he just passed away, too. His name was Enrico Pinardi. And he became kind of one of my art fathers. He was sort of, kind of, real hard Boston accent, when he talked like that. And it would be like, all right. He’d be sarcastic, in a nice way. But he was doing that to get you to really kind of overcome it. And it was a life lesson. And he was brutal in his critiques, but it was done to make you overcome that. And he immediately, he and I really hit it off. And he got me into the work of H.R Giger, who did Alien. And that was 1979 when OMNI magazine made Giger a star. I mean, remember OMNI magazine? That was-

Jesse Kowalski: I loved OMNI magazine.

Bob Eggleton: These galleries of artists we’d never heard of and you’ll go, oh my God, these are incredible pieces. And it was a high-end… OMNI, you could buy it. They had TV ads, you could buy it at the supermarket checkout. And anyway, it was that. And then when Henry got me… You call him Enrico, we call him Henry. He got me into looking at some of these great artists that I really liked, that are fine artists. And they could be called illustrators, too, but they were more fine artists. And there were some of these other people… And his own work and his own thinking, which is very different from mine, but it was also inspiring. It was also inspiring. So he became a major, major, major voice in my life. And he had this… He said, “Okay, kiddo. Kid. Kid, you got to go out and do it.” That’s how he talked. “Okay, kid. You got to go out and do it.”

And he was one of the… So he’s a great influence in my life, and that was around 1981. And he was the one that extolled a lot of realism and even representationalism, because he was what we call old school. He came out of the… You got to draw. He was really into drawing. “You got to draw.” Like that. And at the time, even some of the other teachers at this place, the younger ones were against the whole… They were like, “Well, you don’t need to do that. You can do non-representational stuff and take cardboard boxes and pile it up in the corner.” And it was just, again… I’m not against art schools now, I’m just saying, it was the time. It was forty years ago.

Jesse Kowalski: This concludes part one of my interview with Bob Eggleton. In next week’s episode, we delve into his early career, his process and the love of his life, Godzilla. It’s an interview you won’t want to miss. To watch the video of this podcast, or to see the images referenced in this episode, please visit nrm.org/podcast. New episodes from The illustrator’s Studio are released every Monday. For questions or comments, please email us at podcast@nrm.org.

VIDEO

IMAGE GALLERY

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration

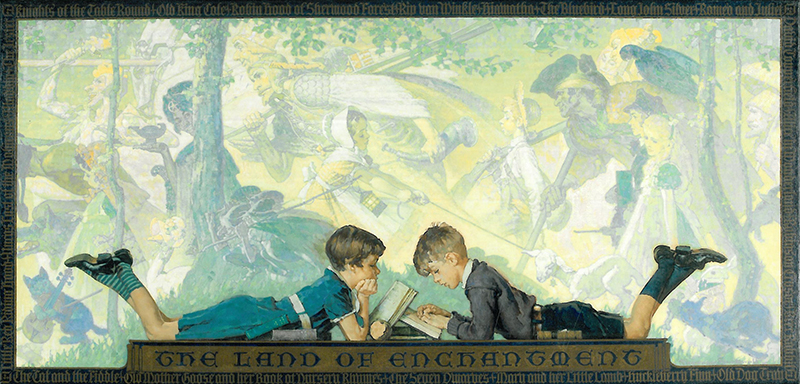

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration explores fantasy archetypes from the Middle Ages to today. The exhibition will present the immutable concepts of mythology, fairy tales, fables, good versus evil, and heroes and villains through paintings, etchings, drawings, and digital art created by artists from long ago to illustrators working today.

The exhibition Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration is organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA, and will be on view here from June 12 through October 31, 2021.