Episode 09: Bob Eggleton (Part 2)

Jesse Kowalski: Welcome to The Illustrator’s Studio. I am Jesse Kowalski, Curator of Exhibitions at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. The Illustrator’s Studio is a weekly interview series, a project of the Museum’s Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies. In part two of my interview with Bob Eggleton, we explore his early career, his meeting with innovator Ray Harryhausen, and his favorite Godzilla film.

What was the first artwork you sold?

Bob Eggleton: Oh, my first professional sale, I was 16 years old, and I did a painting of a landscape, of an English landscape, with this mill on it, and it’s in Wales, I think. And I sold it to one of my mother’s friends. So she commissioned it, and I got a whole $50 for doing it. And it was a 16 by 20 painting. And boy, that was a lot of comic books back then. And it was my first professional sale, and with that came, yet, something else. But I wasn’t a professional artist at the time, but it was kind of like my first sale. And then later on, I had kids asking me to draw superheroes for like 50 cents, and I would do that, and that added up to a lot of 50 cents. That was in high school. So I was doing that back then and then right after that, I was kind of champing at the bit to go and do artwork.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah, and what was your first illustration job?

Bob Eggleton: Probably, I did a lot of work for… It’s a little bit vague in the past. I did a lot of work for a lot of local papers. They had like this thing called the New Paper, which, actually, was kind of a free press kind of thing, an alternate kind of a rock and roll, free press kind of thing, and I did cartoons for them on a weekly basis. That was nice.

At the same time, I had gotten a job working at an art supply store. I literally walked into the place and landed this really good job with full benefits. I got a 40% discount on the art supplies and to the point where it’s an old mom-and-pop place. It was on Angel Street in Providence. Or Thomas Street, sorry. So it was a very historic location, which the actual address is mentioned in an H.P. Lovecraft story. That’s how historic. And right around the corner was where Lovecraft lived. So I was in the neighborhood. Anyway, this store would say, “Hey, Bob, we got these new oil paints and the rep said they’re really good. Could you get them home and give them a bash?” They got these new acrylic paints, so as a result, I started getting all of these. I’m just amassing this great art supply collection for like nothing.

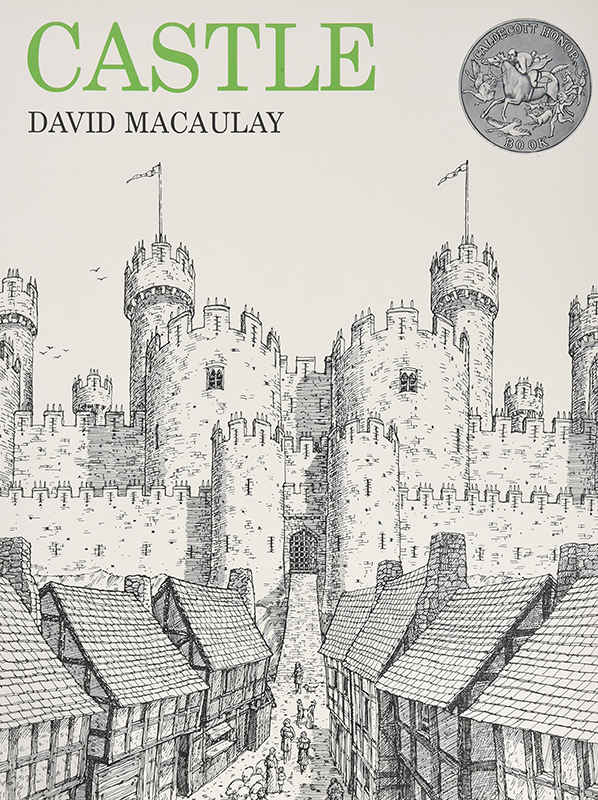

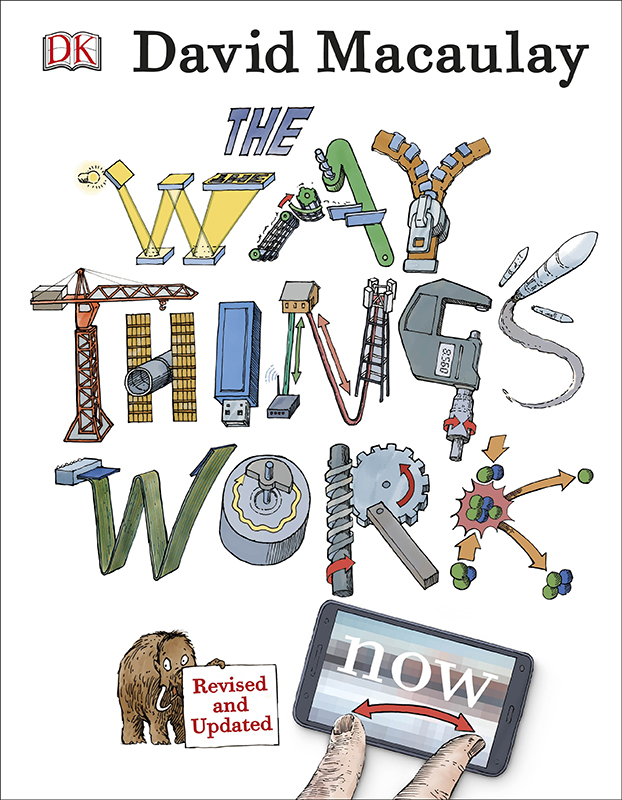

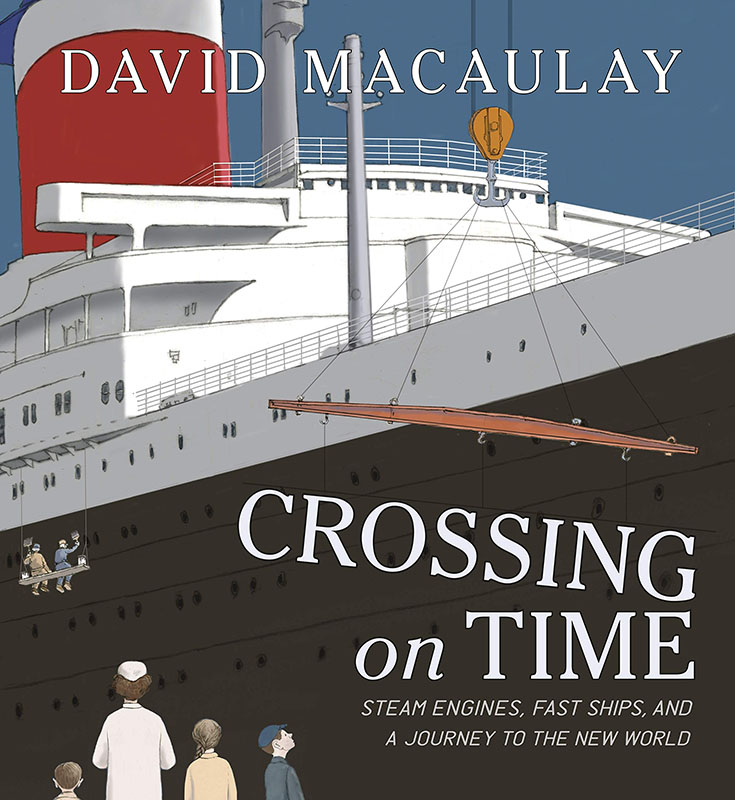

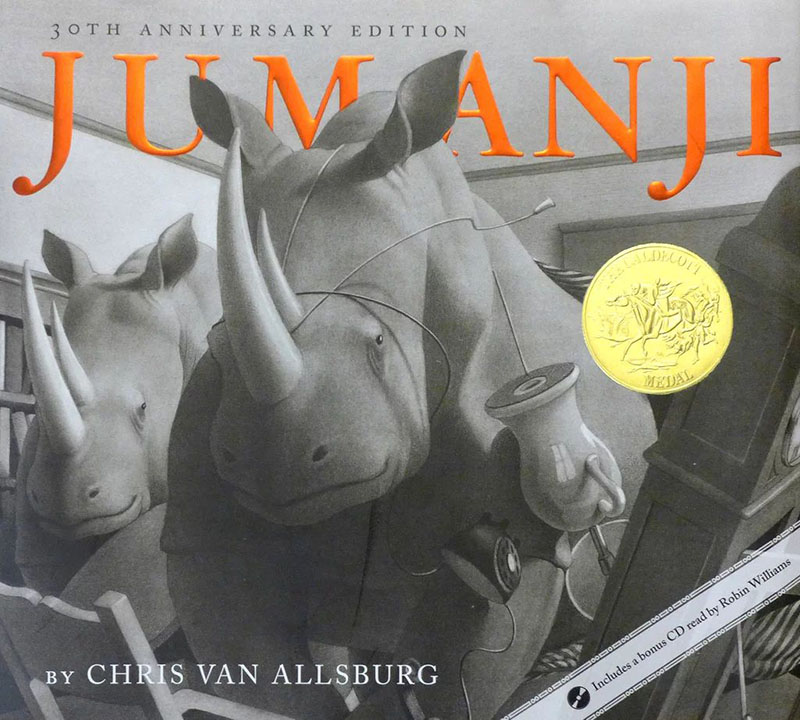

And the school catered to RISD. So what had happened was RISD was right next door. All the teachers came in, and these are guys like David Macaulay, Chris Van Allsburg. Big name guys. And they would say things like, “Hey, why don’t you come over to work? I’m doing a critique with the students. Come on over.” And I’d come over, walk in, sit down, sit in the back, watch the work get critiqued, and I’m thinking, “My God, I’m getting a RISD education for nothing. It’s great.” So that was one of the perks of doing that. And I had this good job, where I taught the students all the time, and I asked them how they were doing, and what they were learning, and things of that nature. It was a great little fun thing, and they were closed on weekends, so I had my weekends off. It was great.

Jesse Kowalski: And did you always intend to become an illustrator of fantasy and science fiction?

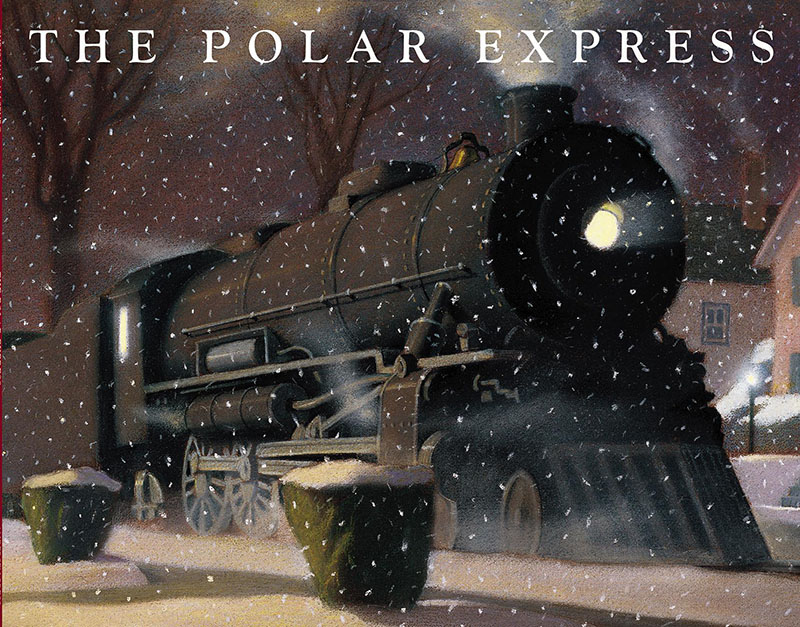

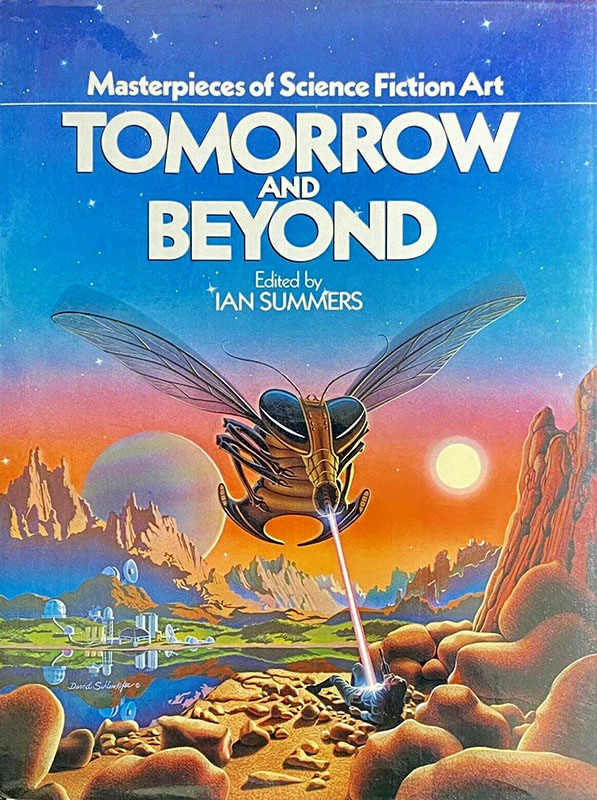

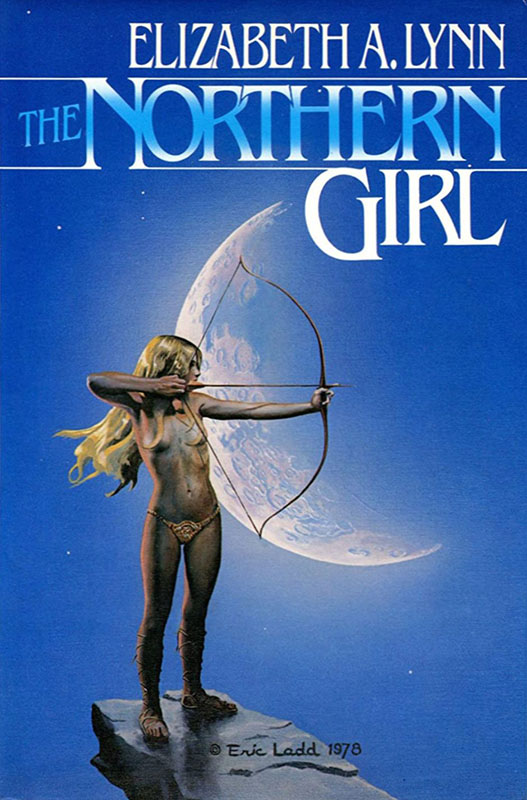

Bob Eggleton: I’d always wanted to, yeah. And the other thing that happened was, in 1979, this is a very big moment for me. Well, ’78, I picked up a book called Tomorrow and Beyond by Ian Summers. It’s a watershed book, and it’s got all of the newcomers at the time, Michael Whelan, Carl Lundgren, Don Maitz, Rowena Morrill, all of these artists who were all newcomers and had the Hildebrandts and everybody in it. And I said, “This is amazing stuff.” And there was no Amazon. I sort of bought it at Waldenbooks then. The next thing I knew, I got to know a guy named Eric Ladd, who was a book cover artist. The local paper did an article on him. So I called him up, and I said, “Can I come down and talk to you?”

This is kind of what I want to do, so I went down and spent the afternoon with him, showed him my work. It was very spotty, and I was just learning some things. And he just saw so much in it, and he gave me so many tips to work with, and how to do this, and how to deal with this. And so I was on this learning experience with Eric, and then he said, “Well, you got to really come to a science fiction convention. I got a good one for you. It’s called Boskone.” And I said, “Really?” He said, “Yeah,” he says, “It’s at Boston,” and he goes, “You get to the bus stop,” and he said, “Go to the Sheraton,” he goes, “I’ll be in there,” and you’d come and see the art show, and it was like $5 to get in.

So this was February 1979. It’s a freezing cold day. I went up there and I walked right into Michael Whelan’s The White Dragon painting. I walked right in the room, and there it was. That’s the first thing I ever saw. And it was like, bang, my jaw hits the floor. It was so cool. And I saw Don Maitz’s work. I saw all kinds of people, Cortney Skinner. I saw… Eric Ladd was there, and then Carl Lundgren was there, and Ron Miller was there, and all of these great guys that I had only seen this stuff in magazines, and that day, I think, “There was the art.” And so I said, “That’s it. This is what I’m going to do.” So that was a big moment for me.

Jesse Kowalski: And when did you know that you’d finally made it as an illustrator?

Bob Eggleton: Well, I started going to these conventions, and what had happened was a publisher named Jim Bain came up to me. And this is a very different time, 1982, ’83, and what was happening was all the science fiction universe converged on these, professionals, art directors, editors, and writers. It was the perfect storm to associate with these people. And they’d have parties at night where they would get, I mean, it’d be great for them because it was a big tax write-off for their company, where they would sponsor a big open party. So everybody would come in and we get cover flats of upcoming covers, so it was like this nice little gallery of stuff I was collecting.

And then you get to meet them, and then I met this one guy named Jim Bain, who was an old-fashioned editor, he’s passed away in 2006, but at the time, he was like Don Wollheim and a few others that were kind of discoverers. David G. Hartwell was another one. They would discover writers. And he said to me, he looks at my stuff, and he said, “I would love you to do covers for my new company called Bain Books,” and I was like, “Yo, I’m there. Okay.” So I sent some slides down, and he bought a slide off me, which was great. And that was my first paycheck for a book that… what we call pickup art. Then he said, “I’ll give you a book to illustrate.” So he hands me this big, thick manuscript, then he says, “Go read that. Come back with some sketches,” and then we’re off and running.

And that’s kind of about the time when I knew, when I was getting checks per month, I knew that I really had done something really great. And then it was not long after that that I got nominated for a Hugo in 1988, my first Hugo Award in 1988. And I would stay on the ballot until 2012, in one way or the other, and I won eight Hugos, and I won one for best related book in 2001. So it’s nine altogether.

Jesse Kowalski: I’ve been to your residence and your studio, and I noticed that you have a treasure trove of popular culture items. You had toys of all kinds, several Godzillas. I don’t know how many you’ve got…many art books. So it seems to me that you, like me, are a man who never grew up.

Bob Eggleton: Oh, that’s what’s really weird. I’m 60 years old, and I don’t feel like I’ve grown up. Ray Harryhausen said to me. I once had breakfast with Ray Harryhausen. This was a great, awkward moment in my life, and I’m going to tell you about it. It’s hysterical. I was at a toy and model show that was in Boston in 1994, and the guest of honor they brought in was Ray Harryhausen and his wife, Diana. And, of course, they enlisted me. I did the T-shirt design for… So I had to do Ray Harryhausen monsters on it. And they gave me a hotel room for the night. And I had a table, and it was all picked up. It was great. And Ray Harryhausen comes up, and he’s like, “Oh God, I love your dinosaurs. I love your art.” And so Ray was like all that.

So we’re sitting at the breakfast table. It’s Ray Harry… It’s him, and me, and a couple of other sculptor guys, and we’re just talking like kids, about why we love ’33 King Kong, why we love that movie, and what we would have been if we hadn’t seen that movie. And so it was my turn to go to the podium. It was kind of a little bit formal. And they said, “I want you… Ray Harryhausen,” and I was still trying to contain my star-struckness, and I’m sitting there. He’s like right here. We’re eating breakfast. And this is the guy that I… I loved all of his movies growing up. And I get up at the podium, and I go, “And next up, I don’t have to say his name, but he’s Harry…”

I literally got tongue tied, and I went, “Ray Harryhausen,” like that. So I was just so absolutely shaking and nervous about it. And we had a great conversation. He hates Godzilla, but that’s it. I told him, I said, and he doesn’t like it because it’s just a man in a suit, I said, “Well, actually, the first appearance was a puppet that they use.” And I said, “You, Ray, have used puppets in yours, and you used a guy in a suit in a couple of your movies.” So I caught him good on that one. And he goes, “Oh, okay. All right.” And he was really great to me. That was a really great moment.

Jesse Kowalski: What is your most meaningful possession?

Bob Eggleton: Probably… Well, I don’t have it to show you here, but it’s upstairs. I have it in a frame. It’s Godzilla’s top jaw from Godzilla 2000. My friend, Shinichi Wakasa, gave it to me in Japan when I went over to visit them in the early 2000s several times. And in 2002, I ended up running from Godzilla in a movie, and you can barely see me for about two seconds. I just fall. It’s like, here’s me, and I fall right out of frame as the camera tilts down. And I got invited to Toho, and we saw the special effects shooting and how they did everything. So rudimentary, actually rudimentary.

Jesse Kowalski: Do you collect art?

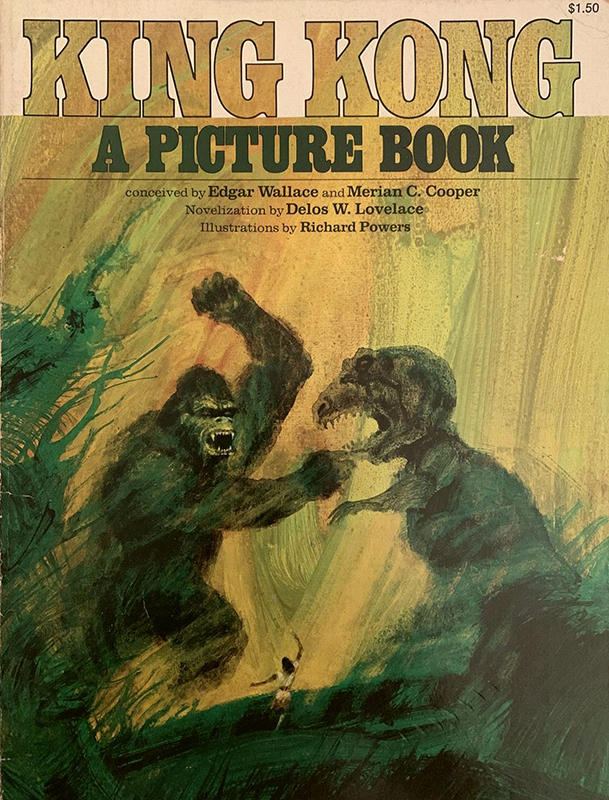

Bob Eggleton: Oh, yeah, yeah, I collect. Earlier last year, about a year ago, I had bought a Richard Powers painting of King Kong. It’s the one where he’s fighting the T-Rex, and it’s a cover to a book that was an illustrated version done for kids, that I bought in 1976. And I always loved that cover painting. It’s real chartreuse green, and it’s Kong and this T-Rex, and Richard Powers did it. And he was just paying his bills doing these things. And I saw this at this gallery. And at the same time, the estate, the guy selling it, he’s a friend of mine, in the reception, he called them, and they said, “Well, we love Bob, so give him a 50% discount.” So they did. I put some money down, and later on, I went up to pick it up. So I collected that.

I’ve got a Morgan Weistling. You ever heard of Morgan Weistling? He was a movie poster artist in the ’90s, and he vacated commercial art to go into kind of these paintings of Native Americans, paintings of little girls with flowers, and this sort of thing. He’s a real, a regular in books like Fine Art Connoisseur, and other things like that. He did the Godzilla painting that was done for a toy that was never made. And my friend, Jane Frank, was helping him liquidate his old commercial art that he didn’t want anymore. And I got this thing in an absolute bargain, and it was like… That’s a beautiful piece. I’ve got a small Don Maitz piece, I own a Kelly Freas, and I have a Paul Lehr painting that I really love, too. It’s really quite lovely. And what’s remarkable about them is these guys, Paul Layer’s a great artist that I love. His stuff is very small. It’s only maybe this big, 12 by 16.

Jesse Kowalski: The field of illustration has often been looked down upon in the art world, as you probably know.

Bob Eggleton: Yeah.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah, even in the world of illustration, I don’t think fantasy artists have quite gotten the respect that they deserve. What are your thoughts on this?

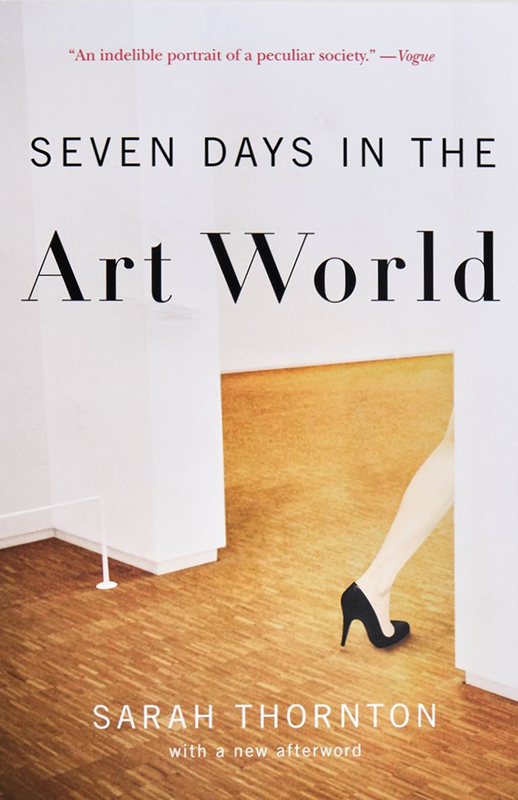

Bob Eggleton: Well, it’s because, I think, the whole fine art thing. There’s a book out called Seven Days in the Art World, I think it’s called, and it literally is the most depressing thing you’ll ever read in your life. It’s all about the fine art, modern art scene, and basically have people told what to buy. That’s the difference with fine art. With illustration, people that buy it and love it, they know what they love. They know what it’s all about. They’re into it. They’re fans of it. They know what it’s all about. With fine art, the problem with that is that it’s all based on like, “Oh, my financial agent tells me this is a good piece,” or whatever. They might not even understand, but that’s what it is.

And fortunately, it’s an invented press. It’s like, they come along and they say, they invent all these things around that, like, “Ooh, this is a modern…” They use the word postmodern a lot. And they say… Because it sounds good. And then they say, “It’s a postmodern statement on our society.” This is what I was dealing with when I was looking at Rhode Island College and RISD back, as I was saying earlier, in the late ’70s. That’s just all it was, was this kind of like this, “Go be a fine artist that doesn’t know how to draw or do anything like that.”

So, yeah. And unfortunately, it’s because it’s not so much that it’s illustration. I find any representational art, a lot of it does get looked down upon. And even back in the day, where they were telling John Singer Sargent, “Don’t do this.” They told Winslow Homer, “Don’t paint the ocean. Nobody paints the ocean. What will we remember it for?” You know what I mean? And he’s another great influence. And people like representational work, but the critics kind of mystify things so that people think, “Oh, well, this is mysterious, and weird, and I guess it must be worthwhile. So I’ll respect it more.”

Jesse Kowalski: What are your thoughts on the younger generation of illustrators of fantasy?

Bob Eggleton: Oh, there’s so many people that have come up, and they’ve had more chances than I ever had in my life. Just the internet. The internet really opened that up. And I mean, there’s kids in high school that are doing book covers and things of that nature. And the younger artists, I just say to them one thing, “Don’t sell yourself cheap. Don’t feel like you’re doing…” Because a lot of people they meet, they do something, and it’s great, but then they do it rock-bottom price. Or they’ll say, “Oh, I’ll do it for exposure.” No, just always hold the line on things and be a professional.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah, I think Donato Giancola posted something about a Hollywood studio looking for an artist to create an artwork.

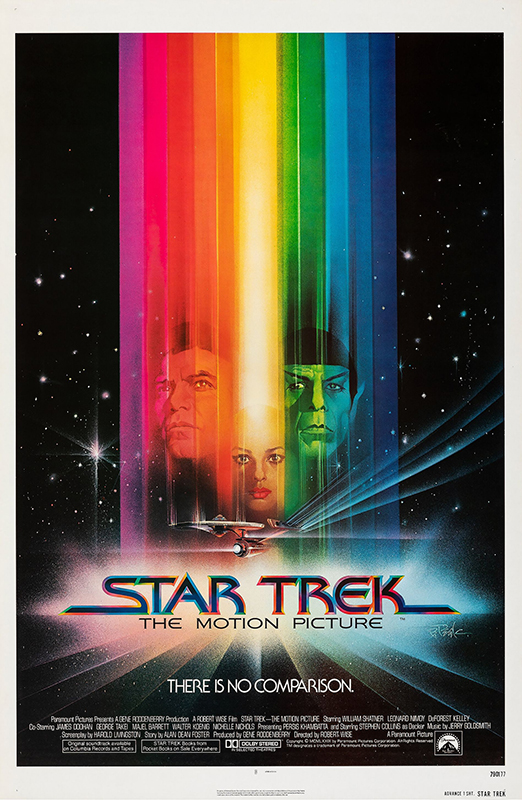

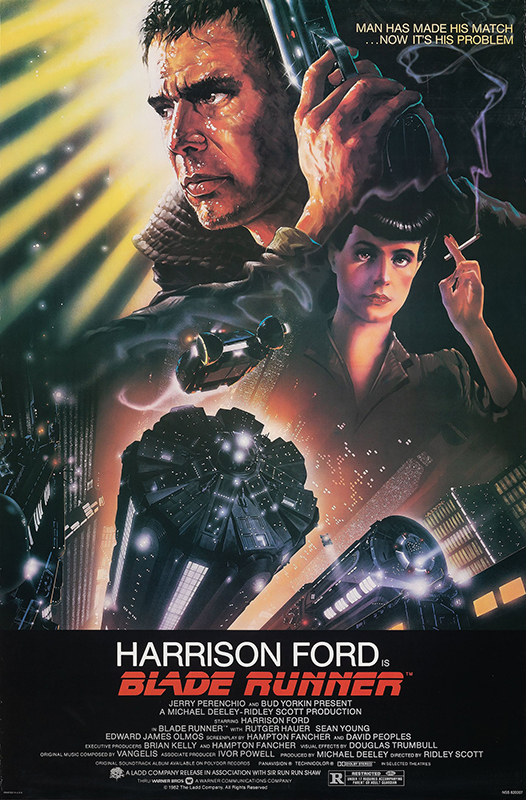

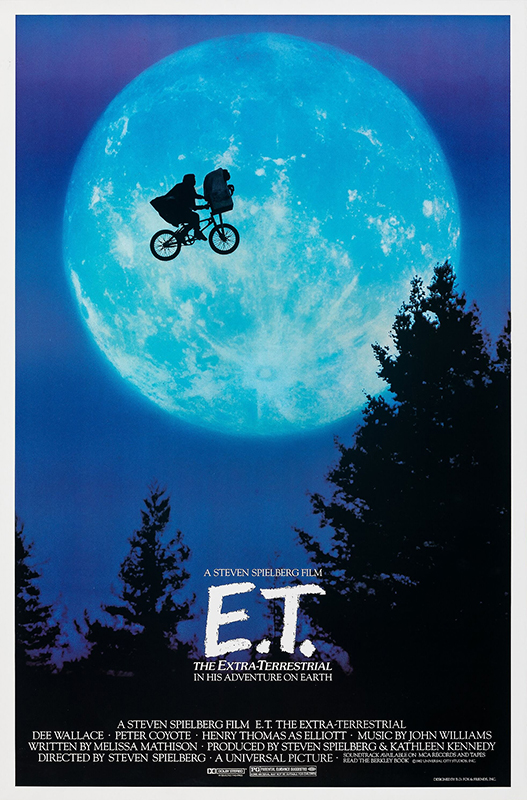

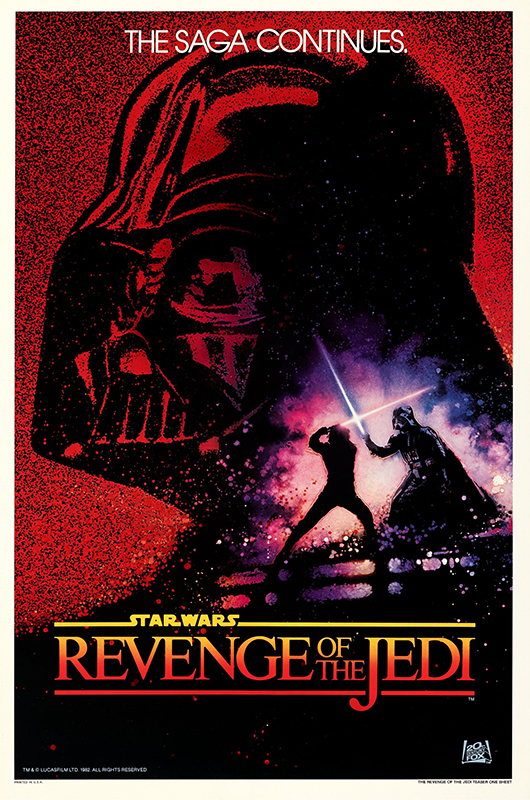

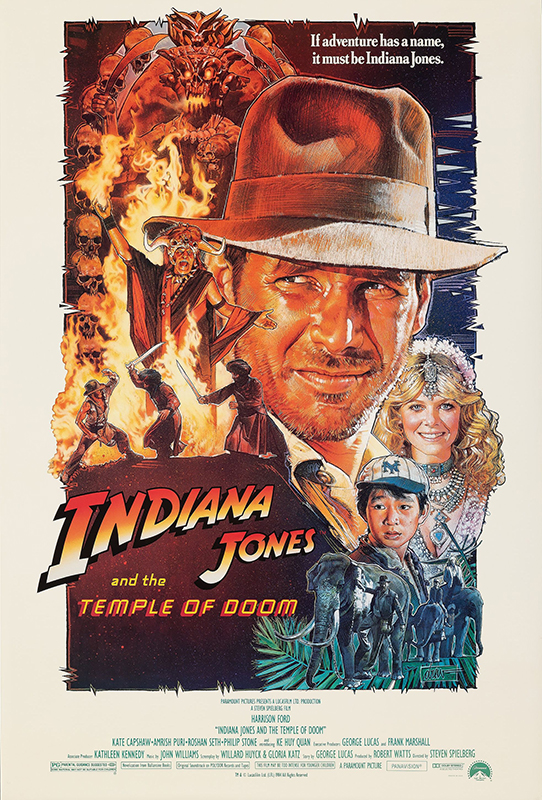

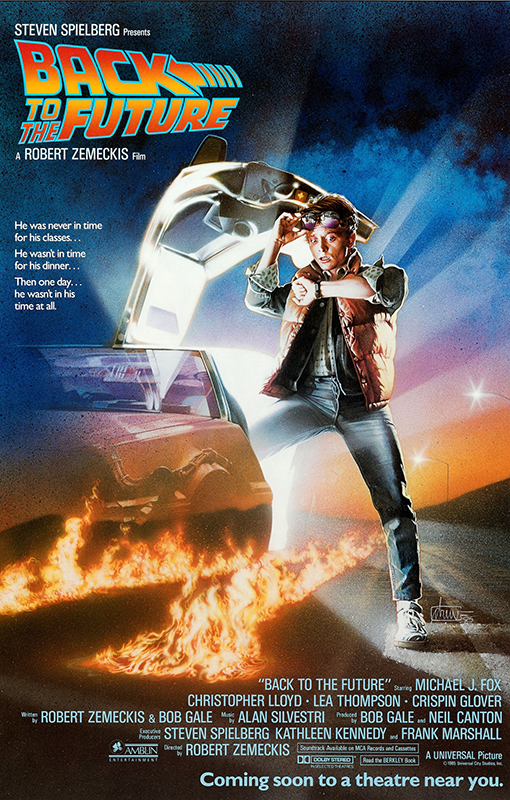

Bob Eggleton: Oh, yeah. But they run it like a contest. I put some comments on there, and Donato really liked all my comments. Because I said the whole thing is like… I love Donato. He’s a great guy. What it was was it’s a way of these… Let’s look back at like Drew Struzan, Bob Peak. Bob Peak is a wonderful artist, and his son is on Facebook, and he puts up, Thomas Peak, and he puts up his father’s work all the time. And it’s so glorious to see these movie posters for the Star Trek movies that were all painted and drawn.

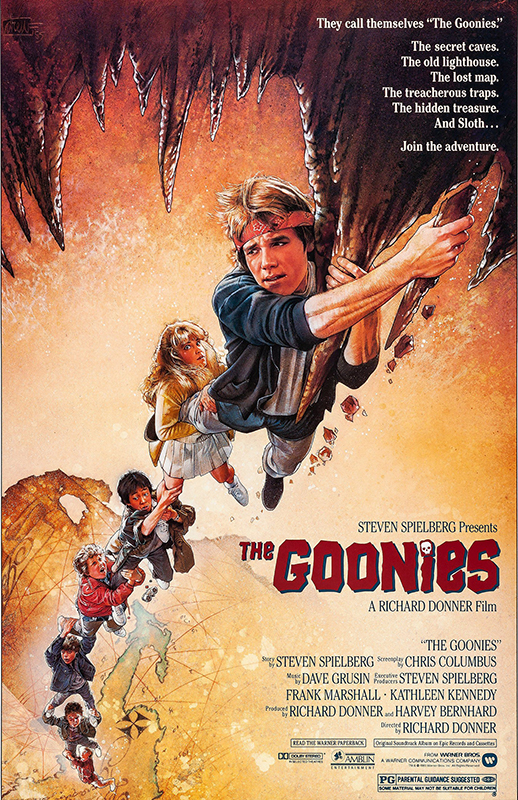

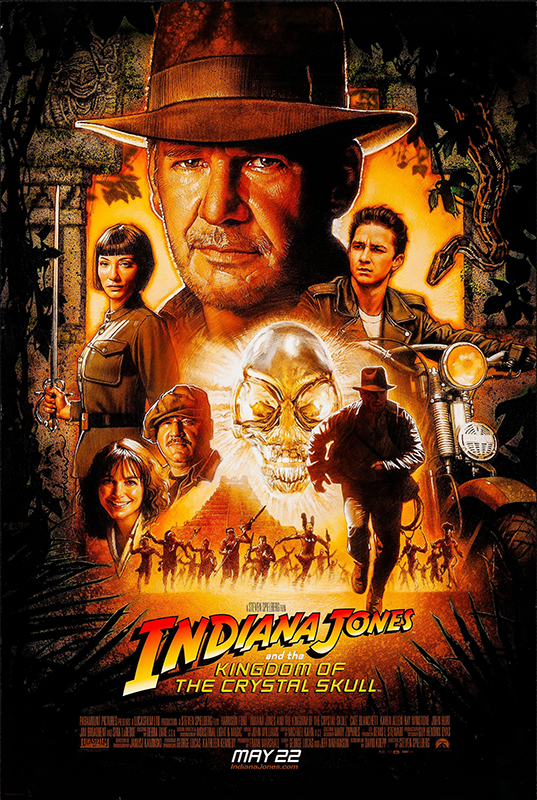

And there was another artist that people might miss. His name’s John Alvin, and he did a lot of paintings in the ’80s and the ’90s, and so much so in the ’90s that he and his wife converted their garage in California into kind of an agency where they did the type, they did the copywriting, and he did the illustration. And he did all kinds of stuff for Batman and all kinds of movies, I mean, just too numerous to mention, and he did a lot of animated films. And his wife, his widow… He died, sadly, at a young age of a heart attack, and his widow wrote a book that Titan Books put out, and she said in it that somewhere in the 1990s, and Struzan would agree with this, they had decided that painted-looking movie posters, that we love, denoted that it was an animated movie. And somebody thought that up. And the big telling thing was when Drew Struzan was asked by Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, powerhouse guys, to do the poster for the last Indiana Jones movie in 2008.

And Paramount Pictures was like, somebody who was about 20 something years old in there, and they go, “Well, I don’t think that… That’s kind of real old school, and it’ll look like a painting,” and… And this is no word of a lie. This is what had Steven Spielberg literally said, “Help us talk to them.” Like that. And I mean, it’s a different generation, and what they did is, as Donato pointed out, the thing is they decide, “Oh, let’s run a contest for these things now, and we keep all the rights, and we’ll use the artwork the way we want to use it.” They did this four years ago with Kong: Skull Island. They had an IMAX movie poster contest. You didn’t get anything for it, except flown to a really cool IMAX theater and you get to see the movie with the cast. That was about it. And the, “Attaboy, you won,” that kind of thing.

Jesse Kowalski: I know you hear from a lot of fans from around the world. Do you have a regular work schedule, or do you base your schedule on the number of fan requests and corporate commissions you receive?”

Bob Eggleton: Yeah, I try to base things on it. In the last couple of years, I had some minor health issues I had to address. And then, of course, the pandemic comes along, and that really, despite everybody, and everybody went through this, despite everybody saying, “Oh, I’m getting a lot of things done,” they didn’t get a lot of things done. They thought they were going to get done. And so I have a kind of a thing where, very prolific, I do a lot of paintings a year. But what happens is, lately, has been interesting. I’m interacting with fans more than anything, and people commissioning artwork for themselves, for their own paintings, rather than doing, say, book covers. I am doing that, I will say, I’m doing the illustrated King Kong, and it’s going to be a beautiful slipcase book sometime, probably next year or probably the 90th anniversary of King Kong, coming up in two years.

And then, I’m also doing another Clark Ashton Smith book, which is beautiful imagery. And these are illustrated niche books, what they’re called. They’re beautifully detailed, an appointed slip case, the whole nine yards. And that’s really what I like my work in. The other thing that cropped up on my life again was something 25 years ago, I did these things called Magic cards. And also, again, I was talking to Donato about this, and he said the the same thing, he did them about 20 years ago. And all of a sudden, Magic has gone through the roof. The artwork, the art on them, it’s like, “Oh my God.” Some of it’s, to its credit, the early work is not even that good. It’s technically not even that good. But one of them, if I saw the price right, it’s sold at half a million dollars.

It was like a painting, like this half a million dollars on eBay, and it was one of the rarest pieces. And, of course, I did art back then, and I did about 22 of these cards, and I sold all of them, like younger when I was younger, and there were maybe a few hundred bucks or whatever. And I’m finding out now that some of them go for a few…thousands. And I can’t do anything about that. You can’t look back and say, “Well, I wish I’d done this.” But what I did do is I got these proofs, these things called Magic proofs, and they send it to me twice a year. My wife and I unearthed them in a closet, and we go, “Oh my God, these people love these things.”

Well, I started advertising them on social media, and I couldn’t keep up with it. It was like signing them, drawing sketches on the back of them, or what they would do is people would send me things, and I would have to alter them. They do a what’s called a Magic alteration, where you paint on the card. And I just did this for a gentleman out on the West Coast, and he paid me well to do this. And then I did a sketch of a card I did in 1997. I redid the sketch because the card was only about this big originally. Now I did the sketch, something like this, just recently, and much better. I’m a better artist, and I’m better at everything about it. And I’ve got a guy, and they’re going to auction it.

And we did another auction of another sketch, and it was a 9 by 12 sketch that sold for like $400. It was a lot. It did really well. And so I sort of morphed into this other way of doing things that… Back in the ’90s, I was doing, mostly, a lot of company stuff, collector plates, and all this kind of stuff like that, and now, I’ve morphed into much more personal commission and interacting with people directly, I think.

Jesse Kowalski: What are the most important factors that you find in creating an artwork? Is it the composition, lighting…?

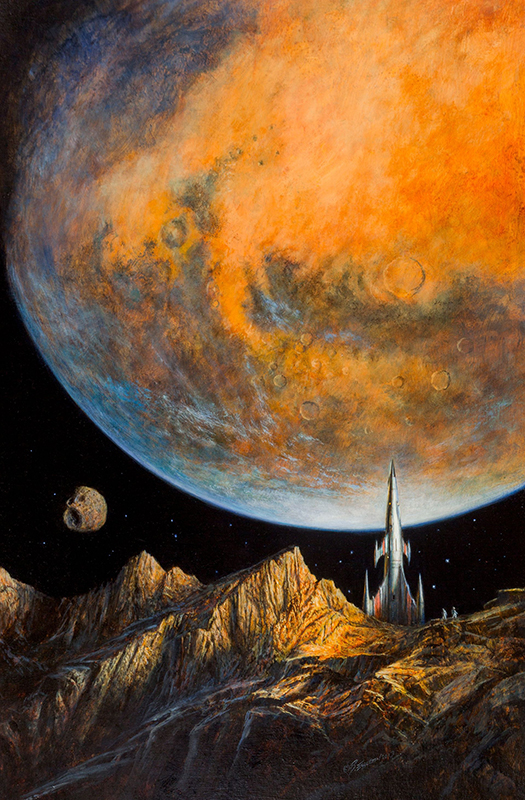

Bob Eggleton: Lighting, and the color, and there’s got to be a simplicity to it. I’m a guy that likes simplicity. If anything’s too crowded, it’s just not me. I don’t do that kind of work. I know artists who do that kind of work, and they’re great at it. That’s just not me. I do something with a very central focus. That painting I did for the show that’s coming up, if you look at it, it’s a very central focused piece, and that’s how I kind of do things. It’s kind of like… Another artist I’m inspired by, his name’s Arnold Böcklin, and he did a series of paintings called the Isle of the Dead. And if you look them up, they’re so, so foreboding and scary, and he did five of them, different ones. And I did my own homage to him by involving the Isle of the Dead in an illustration I did for a book cover, and it worked out really great. It was an absolutely perfect use for it, so yeah.

Jesse Kowalski: And what is your most popular painting that you’ve created or the one that fans find most beloved?

Bob Eggleton: Oh, man. That is a hard one. Lately, I’ll tell you straight, it’s been that Cthulhu painting that I did for you. I have more inquiries on that, and I’ve sold prints of it and giclees of it, which I have available at the Museum, by the way. And I’ve had other things. I’ve had other paintings that are… My dragon paintings are very popular. It’s hit-and-miss. It depends who the fan is. It depends what they like. It depends who they are. Some people like the straight science fiction stuff. They like my spaceships. They like like a spaceship on Mars, like a pointed rocket on Mars. That’s what they like. And so I’ve done a few of those in my life and those are very popular.

Jesse Kowalski: And what is the thing that makes your work most worthwhile?

Bob Eggleton: Wow. Just the fact that it’s just like you’re making something. It’s tactile. This is my thing about actual physical art, it’s tactile, and you put your fingers on it, you put your hands on it, you can touch it. It has a presence. And that, to me, is what it is. It’s the fact that I can touch it and work with it, and I can actually work on it and with it. And nothing against, I know this is probably going to answer another question we had in there, nothing against digital artists. I think there’s some wonderful digital artists. And it has nothing to do with the medium, it’s to do with the talent. The problem with a lot of the digital artwork is some people think anybody can do it, and it just takes Photoshop, and I can, “Oh, look, I stuck Aunt Harriet’s head on Uncle Henry’s body. I’m an artist.” No, you’re not.

Jesse Kowalski: So you’ve won a number of awards in your career, including all the Hugo Awards I mentioned. So how does it feel to be acknowledged as one of the top fantasy artists of our time?

Bob Eggleton: Well, it’s great. I don’t tend to not believe my own press. I don’t let it go to my head. I just say, “What’s your next, what’s your best picture, your next one?” I’ve still got so many pictures that I want to paint. Life is getting on. I went from 30 to 60 like that. I can sort of explain where the last 30 years went to, but it’s the last 10 years that really freaked me out.

And yeah, so it’s kind of a weird feeling, and I got these things in this, and I have my differences with some artists, say, they have their own cliques and their own visions of things and what they think is important, what would they think isn’t all that, and there’s sort of a lot of debate that goes on like that. And I’m still, always, I’m in a situation where I take on projects I like to do, rather than things that I have to do, which is a nice feeling. And what’s happened to illustration, lately, has just, it’s really been suffering at the fate of, again, people thinking they could do something easy and cheap and do it at home.

Jesse Kowalski: And have you found it to be the case that a certain character you’ve created resonates with fans more than others?

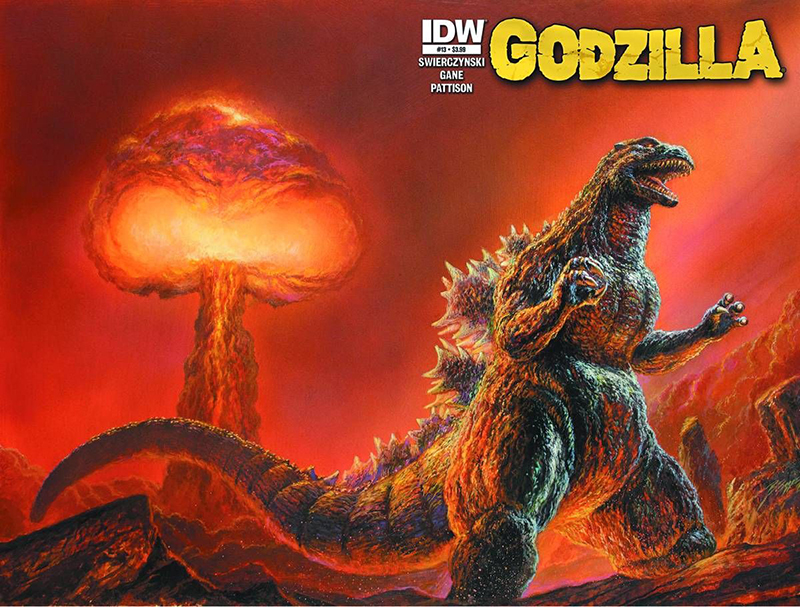

Bob Eggleton: Yeah, I mean, I get like a lot of the Lovecraft requests. People liked a lot of the Lovecraft type of things. And of course, I’ve done a lot of Godzilla paintings in my life, and people like Godzilla and all that. And the thing with Godzilla is that I’ve done very well and got very famous doing some of that stuff. The only trouble is, it’s not mine. The character belongs to Toho Pictures in Japan. So, in effect, the big money, they make all the money, so yeah.

Jesse Kowalski: What is your favorite Godzilla film, let’s say from the Showa era, 1954 to 1975?

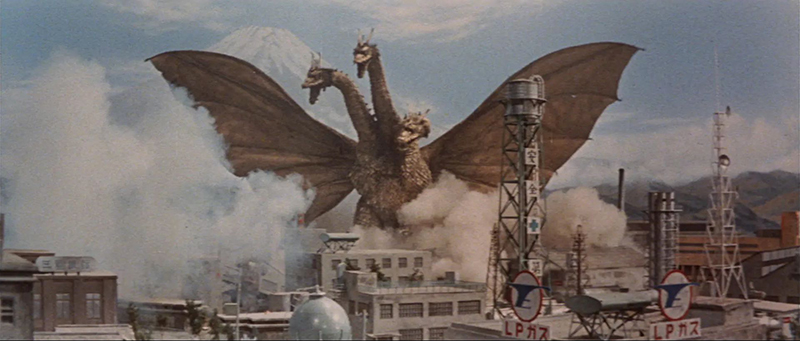

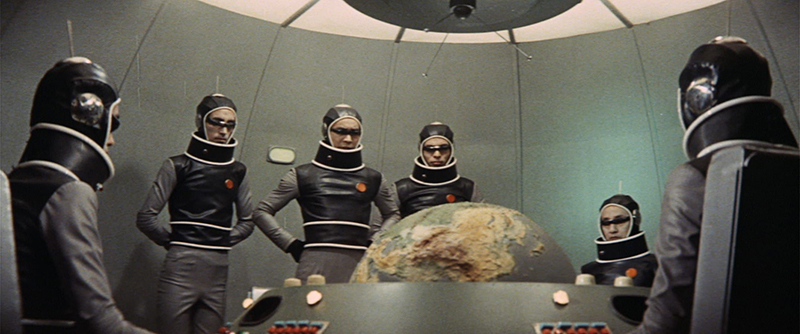

Bob Eggleton: Oh, that’s easy. Invasion of the Astro-Monster, otherwise known as Monster Zero.

Jesse Kowalski: Mine, too.

Bob Eggleton: Oh, yeah. And you know why? Because there’s only 10 minutes of monster footage in it. And the rest of it’s just human action, and the star of it, Akira Takarada, is one of my very close personal friends in Japan. He and his son were friends with the whole family. And he’s now in his 80s, and he’s a very nice gentleman, a very, very sweet gentleman. And then I got to meet Nick Adams’ son one time. That movie really was a turning point with the series because it was the last one Ishirō Honda would really work on until Destroy All Monsters. It’s the last one Eiji Tsuburaya worked on, because he went off and did Ultraman. And he supervised the other stuff, but he really wasn’t actively involved.

And I thought just the human characters in it were really great. I thought Nick Adams is really, with his like, “Whatever’s fair, pal,” and like, “You rat. You stinking rat. What did you do to her?” You know what I mean? That really made it something very endearing about that movie. And the idea that it was aliens from space that came down, and then there’s that scene where Godzilla is pulled up out of the lake with a flying saucer. It’s just magnificent. And that, to me, is my most entertaining one. That’s the one I can just put on and plays in the background, and I know everything going on in it. And yeah, that’s my favorite.

Jesse Kowalski: All right. Well, that’s all the time we have for now, Bob. Thank you so much for joining us.

Bob Eggleton: Great. Thank you. Much success with the show. Hope everybody enjoys it.

Jesse Kowalski: All right. For more information, check out Bob’s website at bobeggleton.com, and our own websites, nrm.org, illustrationhistory.org, and visit the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies at rockwell-center.org.

Bob Eggleton: I’m on Instagram, too.

Jesse Kowalski: As always, don’t forget to subscribe to be notified for the latest content. This has been a production of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

To watch the video of this podcast or to see the images referenced in this episode, please visit nrm.org/podcast. New episodes from The Illustrator’s Studio are released every Monday. For questions or comments, please email us at podcast@nrm.org.

VIDEO

IMAGE GALLERY

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration explores fantasy archetypes from the Middle Ages to today. The exhibition will present the immutable concepts of mythology, fairy tales, fables, good versus evil, and heroes and villains through paintings, etchings, drawings, and digital art created by artists from long ago to illustrators working today.

The exhibition Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration is organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA, and will be on view here from June 12 through October 31, 2021.