Episode 11: Burton Silverman

VIDEO

IMAGE GALLERY

Burton Silverman

(American, 1928 -)

Saturday in September – the debate continues, 1987

Pastel and pencil on tonal paper

Book illustration for Moyers; Report from Philadelphia, The Constitutional Convention of 1787

by Bill Moyers, Ballantine Books, November 1987

Norman Rockwell Museum Collection,

Museum purchase with funds from the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation

and Wendy and Stephen Shalen, NRM.2019.23.38

Copyright 1987 – Burton Silverman

Burton Silverman

(American, 1928 -)

Wednesday, July 25, 1787 (Elbridge Gerry), 1987

Pastel and pencil on tonal paper

Book illustration for Moyers; Report from Philadelphia, The Constitutional Convention of 1787

by Bill Moyers, Ballantine Books, November 1987

Norman Rockwell Museum Collection,

Museum purchase with funds from the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation

and Wendy and Stephen Shalen, NRM.2019.23.23

Copyright 1987 – Burton Silverman

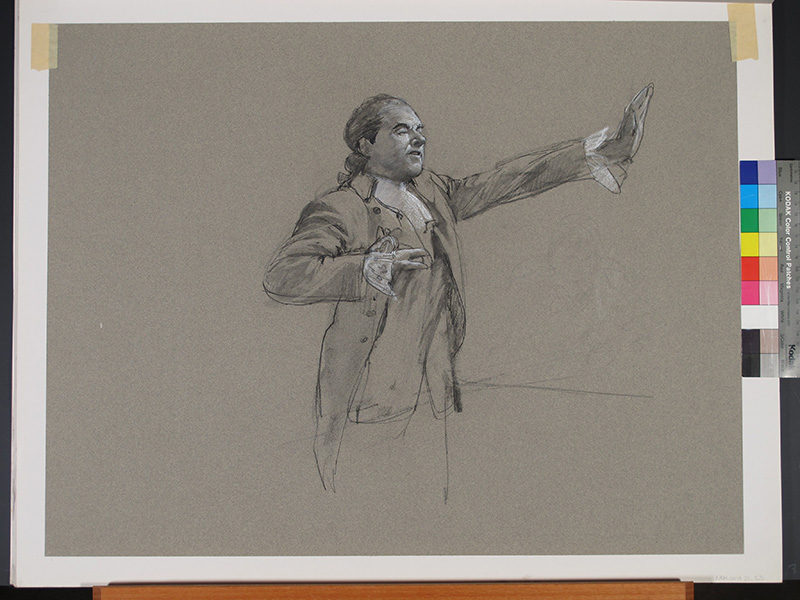

Burton Silverman

(American, 1928 -)

Thursday, August 9, 1787 (Gouverneur Morris), 1987

Pastel and pencil on tonal paper

Book illustration for Moyers; Report from Philadelphia, The Constitutional Convention of 1787

by Bill Moyers, Ballantine Books, November 1987

Norman Rockwell Museum Collection,

Museum purchase with funds from the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation

and Wendy and Stephen Shalen, NRM.2019.23.29

Copyright 1987 – Burton Silverman

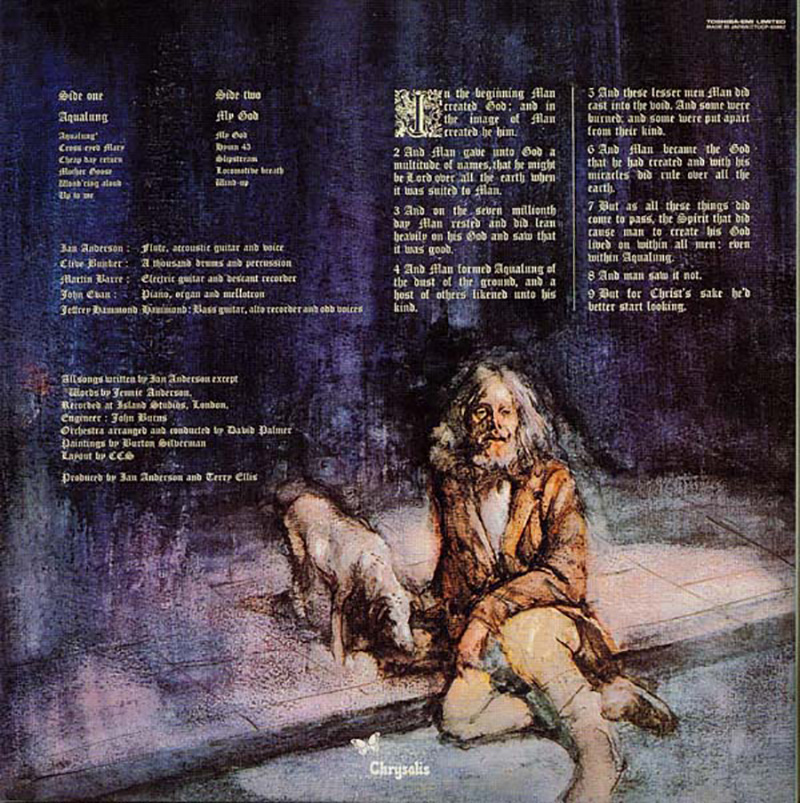

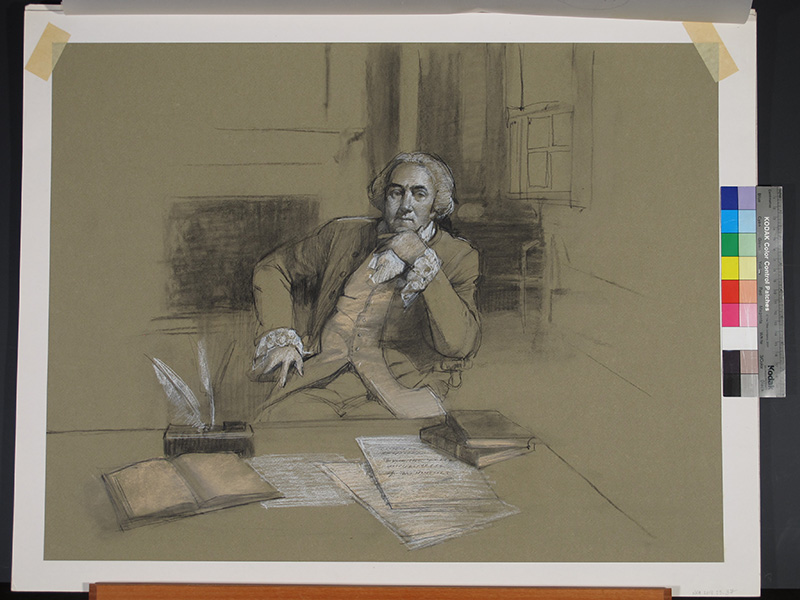

Burton Silverman

(American, 1928 -)

Friday, September 14, 1787 (John Adams), 1987

Pastel and pencil on tonal paper

Book illustration for Moyers; Report from Philadelphia, The Constitutional Convention of 1787

by Bill Moyers, Ballantine Books, November 1987

Norman Rockwell Museum Collection,

Museum purchase with funds from the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation

and Wendy and Stephen Shalen, NRM.2019.23.37

Copyright 1987 – Burton Silverman

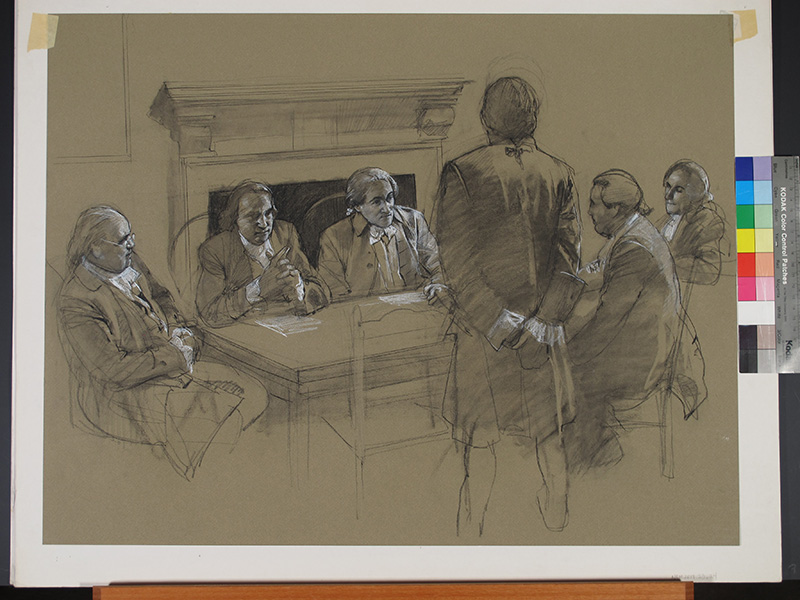

Burton Silverman

(American, 1928 -)

Thursday, July 26, 1787 (Benjamin Franklin, George Mason, and Elbridge Gerry), 1987

Pastel and pencil on tonal paper

Book illustration for Moyers; Report from Philadelphia, The Constitutional Convention of 1787

by Bill Moyers, Ballantine Books, November 1987

Norman Rockwell Museum Collection,

Museum purchase with funds from the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation

and Wendy and Stephen Shalen, NRM.2019.23.24

Copyright 1987 – Burton Silverman

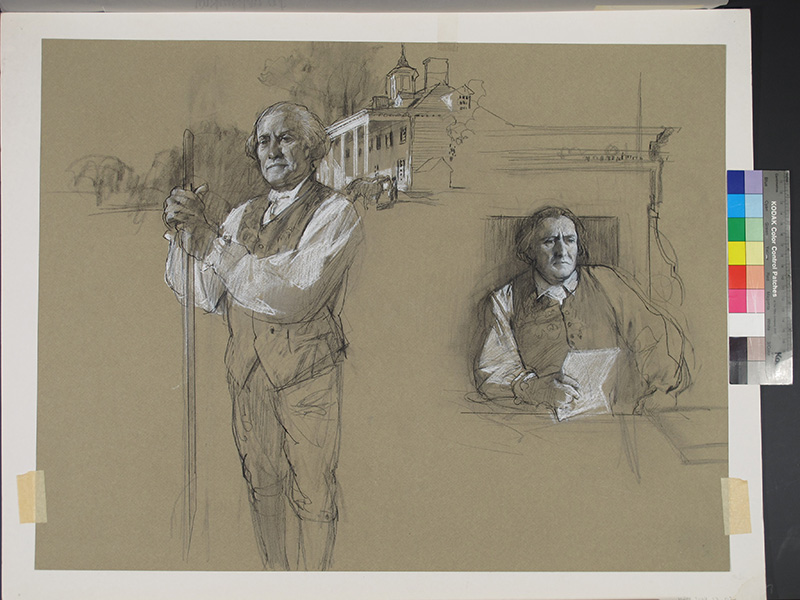

Burton Silverman

(American, 1928 -)

May 25, 1787 (George Washington), 1987

Pastel and pencil on tonal paper

Book illustration for Moyers; Report from Philadelphia, The Constitutional Convention of 1787

by Bill Moyers, Ballantine Books, November 1987

Norman Rockwell Museum Collection,

Museum purchase with funds from the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation

and Wendy and Stephen Shalen, NRM.2019.23.02

Copyright 1987 – Burton Silverman

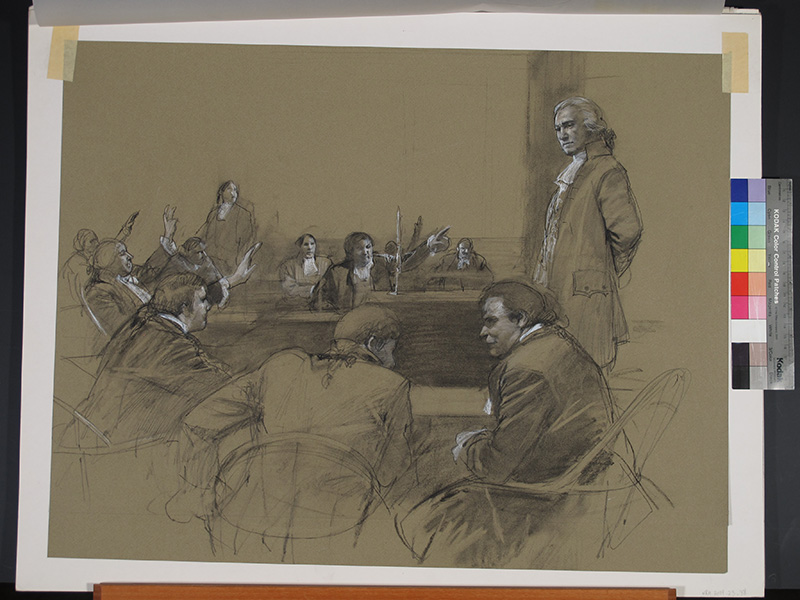

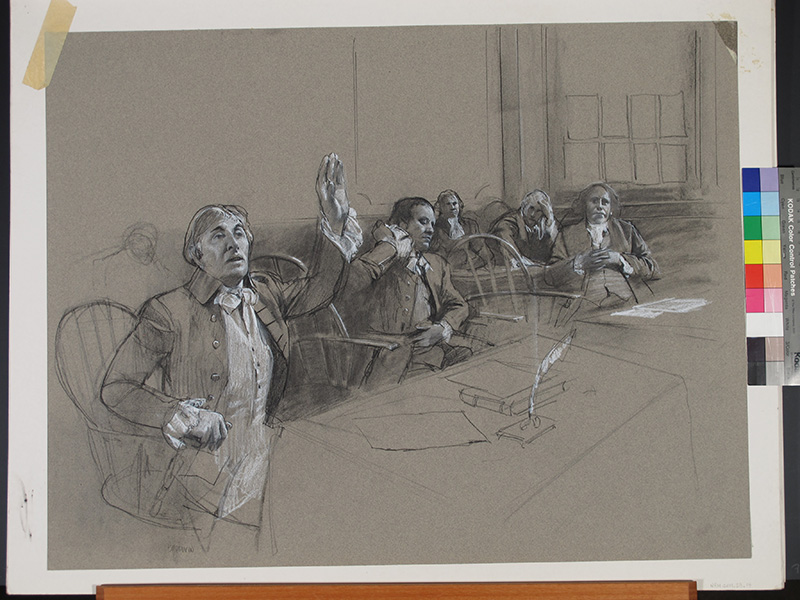

Burton Silverman

(American, 1928 -)

Monday, July 2, 1787 (Abraham Baldwin), 1987

Pastel and pencil on tonal paper

Book illustration for Moyers; Report from Philadelphia, The Constitutional Convention of 1787

by Bill Moyers, Ballantine Books, November 1987

Norman Rockwell Museum Collection,

Museum purchase with funds from the Audrey Love Charitable Foundation

and Wendy and Stephen Shalen, NRM.2019.23.14

Copyright 1987 – Burton Silverman