Episode 03: Donato Giancola

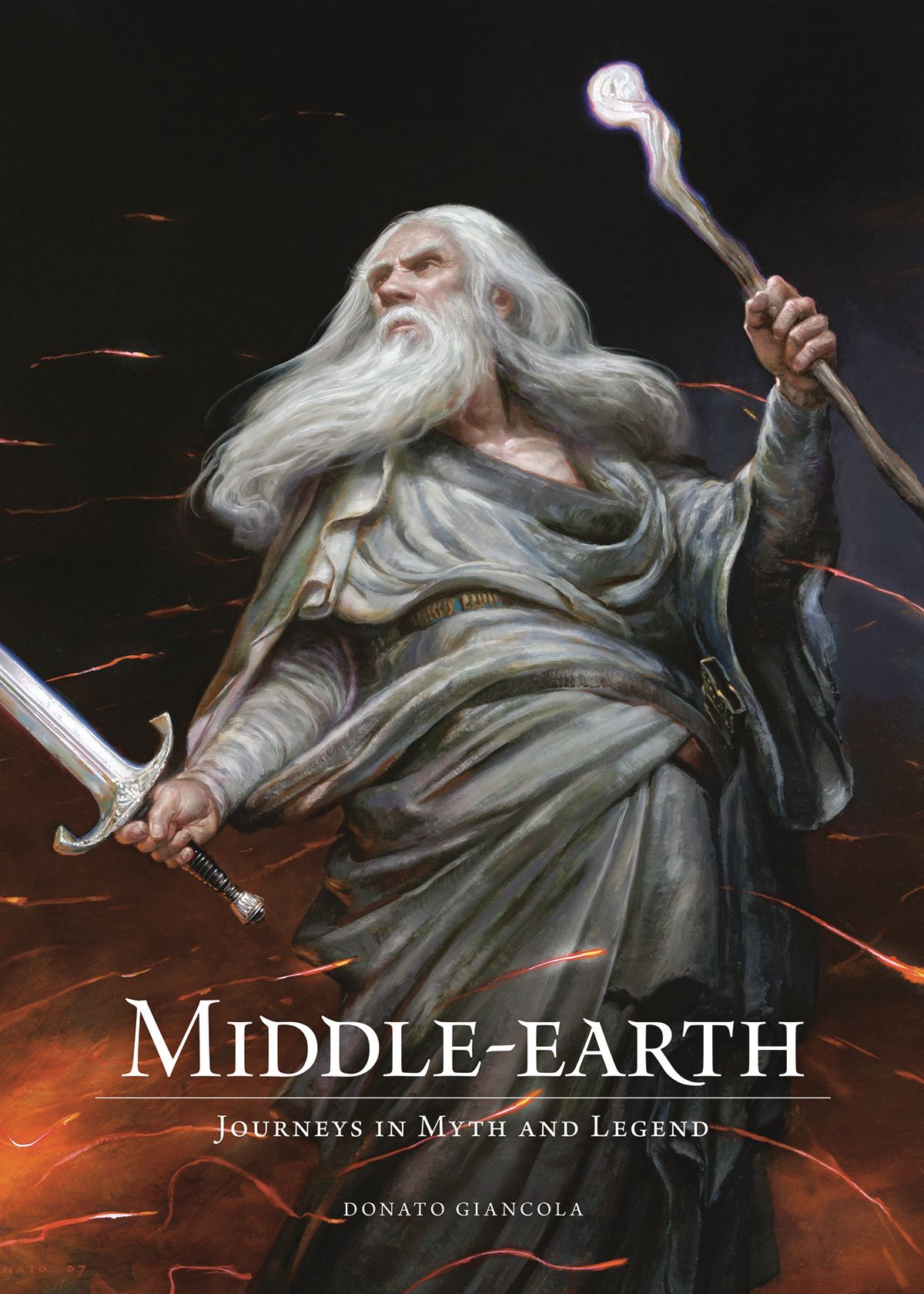

Welcome to The Illustrator’s Studio. I am Jesse Kowalski, Curator of Exhibitions at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. The Illustrator’s Studio is a weekly interview series, a project of the Museum’s Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies. In this episode of The Illustrator’s Studio, we welcome Donato Giancola. Considered a rock star in the world of fantasy arts, in 2004, Giancola was named Best Artist at the World Fantasy Awards and Best Artist at the Hugo awards in 2006, 2007, and 2009. He paints in a classical style that isn’t comparable to many contemporary artists. I would compare Giancola’s work to that of a Rembrandt or Peter Paul Rubens. His admiration for the writings of J.R.R. Tolkien is made apparent in the numerous paintings he has created depicting the Lord of the Rings saga. He has compiled many of these works in the books, Middle-Earth: Visions of a Modern Myth and Middle-Earth: Journeys in Myth and Legend, which features more than 200 artworks. Donato, welcome!

All right. Thank you, Jesse. Thank you, Norman Rockwell Museum.

So you were one of the very first artists I contacted when I was planning the exhibition, because, you know, you are one of the greats.

Oh, well, thank you. I’m just one of the guys, one of the people working out there now, so I appreciate that. Thanks.

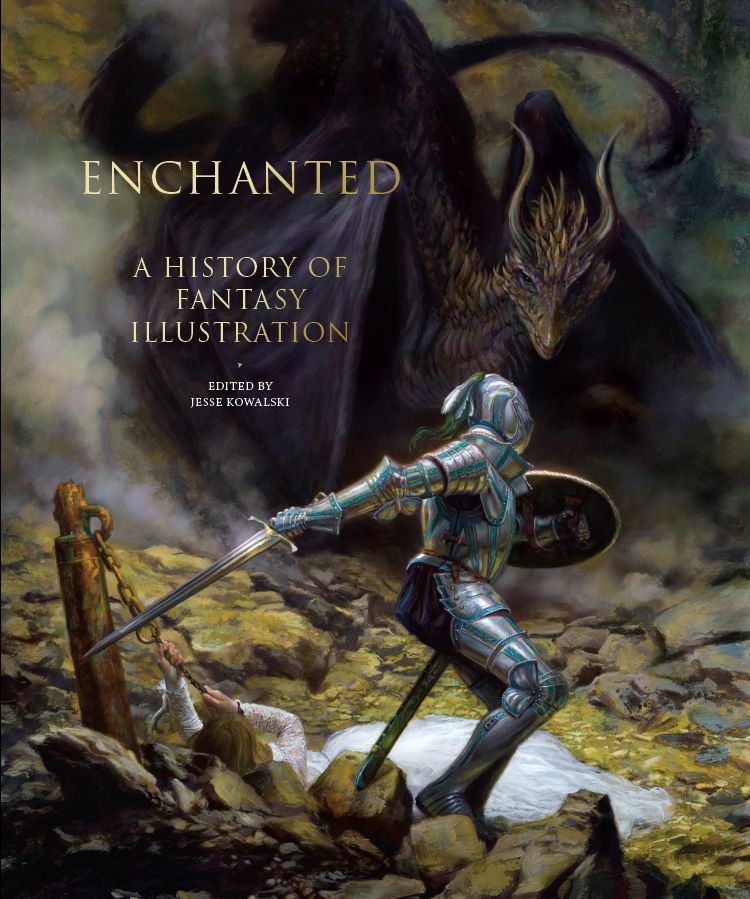

So it’s for an exhibition this summer. It opens June 12th – Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration – and your painting, St. George and the Dragon, is actually on the cover of the book. How does it feel to see your work play such an important role in an art exhibition?

Well, very honored, very much so, and actually also feel very lucky because, you know, you, you curated the show and you know, how many great works of art are in this thing. And it’s just, I, you know, every time I get into a show, I feel lucky to be included amongst my peers, and, here, a historical retrospective. I don’t know what was going through your minds, the publishers’ minds, when you had to like, juggle, like what image to put on, but, I’m, you know, very grateful and lucky to be on there, on that cover, representing the show.

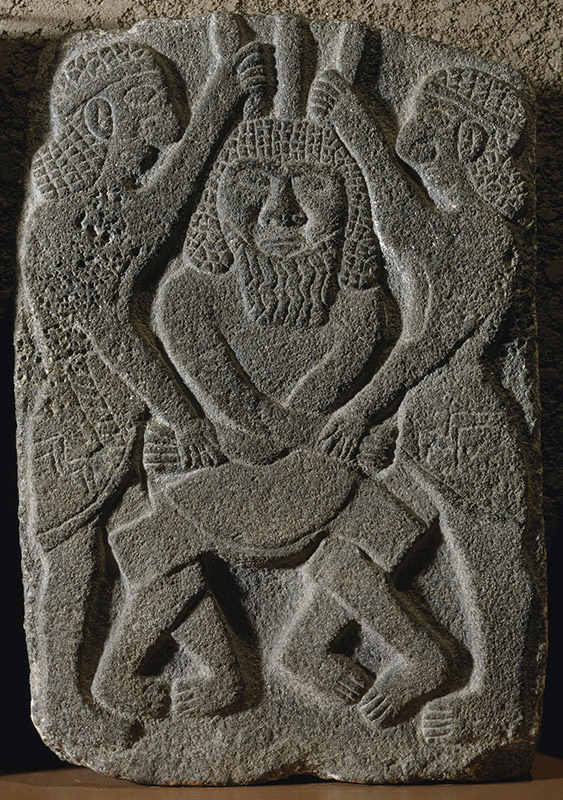

Now the exhibit, it covers… the book covers 5,000 years of fantasy and in the exhibit we have works back to the 1500s or so. So it covers fantasy illustration through a number of periods. St. George and the Dragon of course, is just one of many archetypal images of a man battling the beast that goes back to the Epic of Gilgamesh in 3,500 BC, and your painting is so perfectly composed – such a gorgeous painting. What was your inspiration for painting that one?

Wow. I mean, St. George, like you said, it’s got deep mythological, historical roots, and I can, you know, immediately, as soon as we start talking about St. George and the Dragon, for me, the iconic image of Raphael’s miniature painting… I don’t know if you’ve seen it down at the National Gallery… it is a little St. George and the Dragon, and, you know what, I think it’s maybe eight or nine inches tall. It’s like a manuscript page, but that image just keeps coming back to my mind – a kind of humanity against nature/ primal forces at play. And also the idea of a kind of compassionate act that it’s St. George rescuing somebody, you know, in service to someone else’s needs. So I think that really plays into this wonderful idea of narrative and why… I think that’s why we have fantasy art now that with the birth of it, the growth of it, and the explosion of it, is telling stories and connecting people together over stories.

So with connecting people and telling stories, let’s move on to your childhood. I wasn’t allowed to play Dungeons & Dragons when I was a kid, you know, because of the stigma – it was awful – but…

I remember that there was a wave. My parents were like “devil worshiping,” right, because they had satanic images and things and…

…kids in the basement with the candles. No, but I know that you played it growing up. What effect did it have on your creative development?

None at all. No.

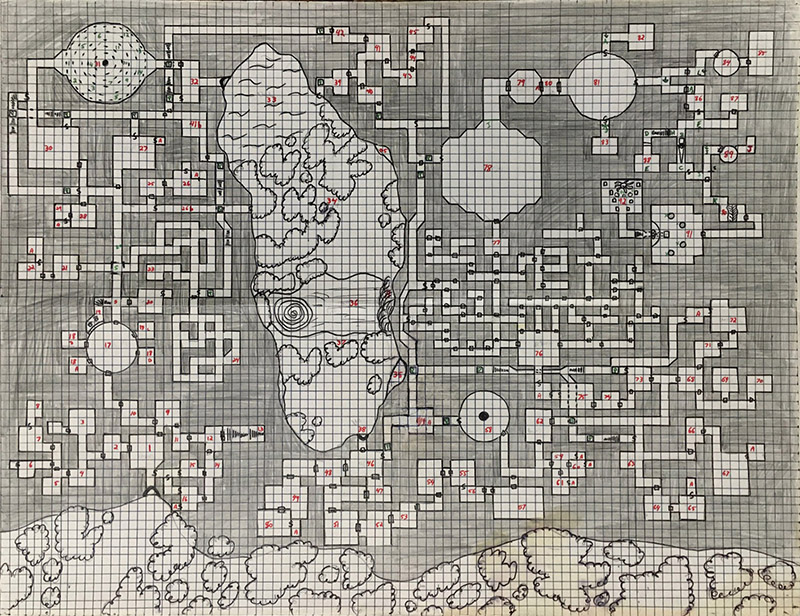

It was probably one of the most instrumental engagements in my childhood; even now like with the repercussions of that. So for, you know, Dungeons & Dragons, those who, who don’t really… who have probably heard of it… but you basically make up your own story. You know, you have somebody who is guiding you like a writer through a story of what these other characters, their friends, play through. I think that for me is what I love so much about it was… here was a chance for me to make my own stories, make my own world/world-building, like making Dungeons & Dragons maps. That’s actually where I first kind of stepped deep into creativity, was distancing myself from the modules that they would have available for most players, and I just made everything myself. I built the world, I drew the maps, populated them, and ran the campaigns as a Dungeon Master for my friends. So that foundation, Jesse, I think, that laid the foundation for me, for the creativity that I then tapped into as a professional – the idea that I’m a world-builder. I rely on some input from like writers and external sources, but really the internal storytelling gets motivated from within. And that again, dates right back to Dungeons & Dragons.

Could you tell us a little bit about your art education?

Oh boy, that’s a long twisty path. Like you, right? We all draw when we’re kids, right? So, I mean, everybody draws, it’s a way of, you know, it’s like you almost learn to draw before you can almost speak, right? The idea of image making, mark making, and all of that. So as a young man, a young child, I just drew all the time. I was prolific just outputting, but I didn’t have my first official class with like an art teacher until I was twenty years old. So I didn’t start… so like most of my work, all my Dungeons & Dragons things, those were all as a hobbyist, as a fan, as just a creative person looking for outlet. So, yeah, at the age of twenty I picked up my first set of acrylics. I tried painting, and realized I needed some help immediately, and I took my first drawing class at the University of Vermont. And that slowly set me on my path towards becoming a professional.

And, so what were your first jobs?

Oh, wow. Well, my first job started soon after that very first class… I worked retail selling electronics, and on a chalkboard, we would… there’s a chalkboard in our workplace… and I would… we used to rent out videos and I would draw the new rentals that came in, like E.T., or The Empire Strikes Back, and I’d draw a little bit of that. And one of the people who came in to rent videos was a local restaurant owner. He saw the artwork… asked if I did anything else. I showed him a few of my new images from my new drawing class, and he hired me to populate his restaurant with images from like the 1940s and ‘50s, like Laurel and Hardy and Billie Holiday and Citizen Kane. So I did reproductions of these people for his restaurant. So it was actually my first drawing class that ended up getting my first professional work.

Does that still exist?

Yes. The old… unfortunately the restaurant burned down, but they were… somebody found some of those drawings out at a marketplace, like on sale. And so yeah, I verified that those were indeed my originals. Yeah.

You mentioned before the impact of art museums on your life. Besides the Norman Rockwell Museum, of course, what museums do you visit for inspiration, and what draws you to visit art museums?

Wow. It’s almost more like the question should be, “What museums don’t I visit?” Because I am a hound. Like the Norman Rockwell Museum focuses on narrative realism, and contemporary illustration as well. But I think what is… what I love about museums is the act of discovery – of stepping into these places and discovering something new, a new way to tell the same old stories. And that’s what I love about the experience of both getting ideas… technical ideas… storytelling ideas from those artists from deep in the past. And museums also represent a curated aspect of that work, is that you’re getting some of the best of the pieces of history, of our history of narrative, history of storytelling and art making. So you walk into a museum, for me it’s like walking into a curated show, like what you guys do at the Norman Rockwell Museum. You’re attempting to present to the general public these valuable voices and the most critical aspects of those voices to present to an audience. So I think that’s why I love going to museums is that it’s inspiring, and it’s, again, an act of wonderful discovery.

Who are some of your favorite artists and your favorite pieces that you like to look at?

Oh, for museums? Wow. That’s a lot. Ah, boy. Oh, here’s an example like, even though these aren’t… this isn’t the end-all be-all of lists, but back in, uh, jeez like fifteen years ago there was a Caravaggio painting that came from Ireland to the States… it was The Taking of Christ by Caravaggio, and I made a pilgrimage up to Boston to see that painting, just that one painting. I realized that it’s never gonna be in the States again, it’ll be forever hung in the National Museum in Ireland never to leave as a national treasure. So I drove up and met my brother in Boston and we went for the afternoon to go look at this one painting. At least I did, I don’t know what he did. I think he wandered around a little bit while I took in that painting.

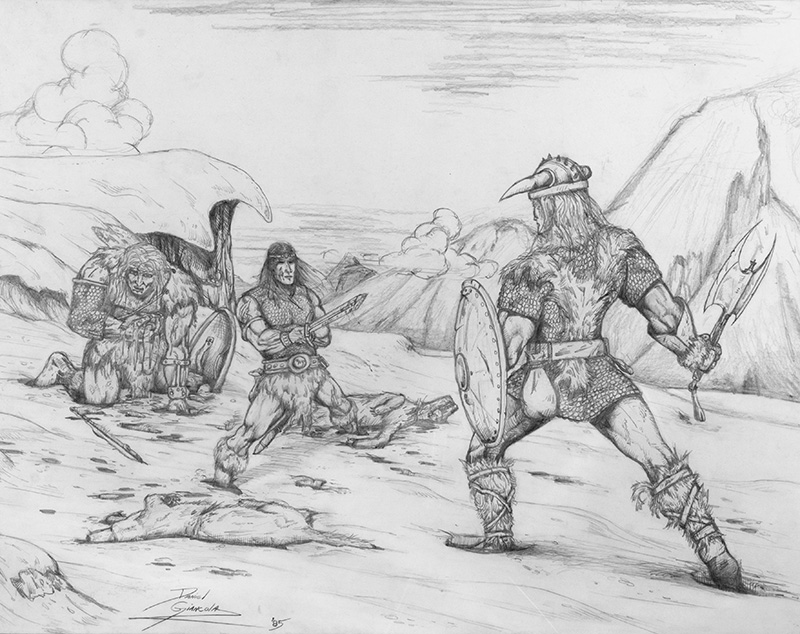

But that’s an example like of Caravaggio, Hieronymus Bosch, and the great classics… Raphael…, but also some contemporary artists, certainly. The Dungeons & Dragons illustrators, from Keith Parkinson and Jeff Easley, Larry Elmore…. I mean, some of these people are, I think, are included in your show as well, right? And to be honest, I tap into a deep and wide pool of inspiration, Jesse, because I just find validation in so many different people, so many different art forms, and then I spit it out into my own work.

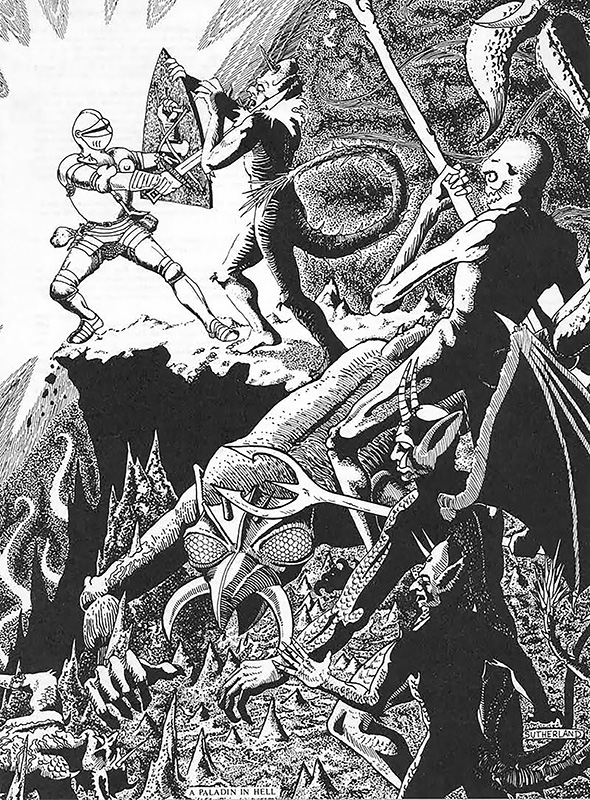

Since you mentioned it we’ll have the very first painting done for the Advanced Dungeons & Dragons set by David Sutherland.

Yeah, David Sutherland… I mean, those images are iconic, like those are forever burned in my mind. I think Sutherland might’ve also done the knight in Hell where he’s fighting demons. And that’s another brilliant piece in the Player’s Handbook, that is, again, that is burned into my head as the stereotypical, you know, passionate knight in armor.

And, what is it about fantasy that interests you?

Fantasy art for me is using your imagination and combining that with storytelling, narrative storytelling. And so science fiction for me is just the same – it’s just using futuristic themes and extrapolated sciences and such, uh, so fantasy art, well, I guess in some ways, it’s also about revisiting what makes us human, like revisiting those stories, the reconnecting to why we make our choices, what we do, how we interact with each other… And art is a wonderful way to kind of revisit these themes and re-digest the recurring nature of what makes us human. So, I think the greatest part of fantasy is that you’re using your imagination, so you’re just constantly in a flux of possibility as a creator… as an artist.

What draws you to J.R.R. Tolkien and The Lord of the Rings?

Oh, wow. It has deep roots, like Dungeons & Dragons, you know, that taps back into our childhood. My brother Michael handed me The Hobbit when I was thirteen. He said, “Here, you might like this book.” This is just after I started playing Dungeons & Dragons and you know those were made for each other, or Dungeons & Dragons was inspired by Tolkien. So it was obvious that The Hobbit, which then led me into The Lord of the Rings and The Silmarillion and The Book of Lost Tales and Unfinished Tales, so I just dove in, like, just this rabbit warren, and I am just forever digging around in there. So, you know, I can’t really say what more than that.

Uh, it’s adventure, right? It is the idea of conflict and resolution, but also I think friendship, like it’s comradery, right? It’s about people coming together, helping each other. So I think that’s what I love most about the novels… of what Tolkien did… is that the way you solve problems, isn’t like… warfare doesn’t always solve it. It’s like the way they destroy the one ring, it’s two friends who sneak their way in, and it’s friendship and love of each other that saves the day, not the big armies that are attacking Mordor or fighting it out in the battlefield.

What do you find is the most difficult part of creating a painting? Do you get like a writer’s block or is it a matter of coming up with ideas?

Uh, I think… ideas… I’ve never had an issue with writer’s block. I’ve never experienced that. So I’ve been lucky that, again, I think it ties into, like I mentioned, like I was a fan and a hobbyist for most of my early part of my life as I drew. So my art was just a free flow way of communicating, of thinking. So I always… I never created impediments to that language. You know, like if I worried about my grammar, right, some people would never write because they would misspell things… they wouldn’t get punctuation right. And so art and drawing was always a free flow of ideas, and so as a professional, again, that just taps in, like, I just never am without themes and ideas. I have a little bit of like a wall over here of little thumbnails, so I’ve got like about a hundred thumbnails of ideas that I’d love to do. And those are like I’m ready, like any moment if I have free time, I’m jumping on that, jumping on that, those things.

And what’s your process for creating works, because Rockwell liked to use photographic reference. Do you use any reference – photographic or models – and what’s your process for creating a painting?

A hundred percent like, I mean Rockwell and those illustrators of the golden age are like, they helped, well, they laid a very strong foundation in photographic referencing. And in part that spoke not so much that they didn’t like working from life, but the time leanness… the deadlines that they had to execute required that they didn’t… they couldn’t have a model pose for weeks on end, right? You had to get the image together, assemble it, and actually Rockwell was very good at taking action, right, getting people to pose and collaborating the action and embellishing the figure. So all of those… are all techniques that I use now. But the idea of, I mean, everything that is inside my picture, like the St. George and the Dragon, as an example… that image, that armor is an assemblage of knights from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The woman, or I guess you could see it’s a woman…

actually, you don’t even know the gender of these characters, but the woman lying down, the maiden is my daughter, Cecilia. But the dragon… I had to make up the dragon. I don’t have a dragon outside, but the wings, the dragon’s wings, I still remember that they’re from the American Museum of Natural History in Washington, DC. So the Museum of Natural History, uh, not the American Museum, I think that it’s the National Museum of Natural History down in Washington, DC, is a bat. I think it was a fruit bat there, and that’s the wings. If you go there, you can see, right, that this dragon and that bat… the images that were inspired by that.

Do you paint at a certain size, or does the size of the painting kind of depend on the theme or subject?

I mean, as an illustrator, I do have certain sizes that I paint…

You paint some very large…

Yeah. That’s just going crazy. Yeah. But, yeah, there’s a bit of whimsy, not whimsy, but, uh, like if I love an idea passionately, then I break away from my needs to execute it for just as like an illustration for a client or for a book cover, and then I’ll make it larger, add more detail to it. Sometimes even embellish the structure, the surroundings a little bit more… But I have created very large canvases when I’ve been inspired by the Hudson River School painters, like Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Church. And those are, again, those are fantasy related, but they are on a much more monumental scale. Yeah, so really, I think, you know, almost all artists tend to work, like according to, you know, their options, right? You know, mostly they’re, you know, like Rockwell was constrained by commercial commissions. But again, later in life he started making larger pieces, right? So that’s… just the opportunity allowed him to spend more labor, and so therefore he did exercise that ability.

All right, so let’s get serious here for a minute. Your work is often compared to that of the Old Masters. But throughout the 20th century, and often still today, art critics have kind of drawn a line between illustration and fine art. Do you consider… I guess, what do you consider the line, and do you consider yourself an illustrator or a fine artist?

Oh, I guess I’m mostly, if you had to, like, when I’m filling out my tax forms, I’m calling myself an illustrator, but again, these are titles that I think other people put on. So I think of myself more as just a painter or an artist. Certainly most of my clients have been commercial-related/commercial illustration: book covers, game cards, advertising, and things. So yeah, in that sense of categorizing I’m an illustrator, but I also came up through, in the ‘90s, when everyone was doing traditional media, but digital was switching over. And so back in, you know, fifteen years ago when huge waves of artists were switching to digital, I stayed as a painter because I still like making that physical object… which is what you show at the museum, right? There’s tangible objects, the physical presence of those artists’ choices, those artists’ touches – the hand manipulating that material.

How were illustrators taught, I guess when you were going to school? Because I know when I was in college in art history, it went from the Impressionists to Abstract Expressionism. You know, we just skipped over Rockwell and the illustrators. Did you have that same kind of experience?

I got skipped over for all… I was actually, you know, you’re talking about fine art. My training, Jesse, was in fine art painting at Syracuse University. So here, you know, like I didn’t, I didn’t… I didn’t really discover illustrators in the terms of that classical sense until I almost left college. Like finding out about Michael Whalen and, you know, obviously there were illustrators I was exposed to with Dungeons & Dragons and fantasy and comic book art, which is what I grew up with. But like Waterhouse… it took me years after, even after school to discover John Waterhouse’s work. So that, like, the blinders that you put on when you study a certain class can be a negative. I love figurative work, I love storytelling,

I love Realism, but I wasn’t exposed to that much of it. In the illustrators’ history, Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth, Harvey Dunn, Norman Rockwell, J.C. Leyendecker… all these names that I now roll off my tongue all came after my college experience. Yeah. But again, that doesn’t mean that you have to be forced into that, right? To look, to learn, and to celebrate it, right? So here I am now as a professional living in that almost direct lineage of those illustrators, right, but I didn’t actually grow up with that. It’s like, you just… I think you fall into it regardless of where you’re coming from, right? Because it is the common ground. It’s a common historical ground that you end up seeking out if you’re a storyteller.

In October 2019, I was lucky enough to sit through one of your sessions where you were doing some drawing for students. Like everyone else, I was just enamored with your technique and delivery and just the excitement you had. And I wondered, do you teach often, or do you find joy in teaching others?

Yeah, actually, I’ve been teaching, boy, almost since I left college. And since 1995 was my first class that I taught was two years after being out of college. I wasn’t a good teacher then. I see I’m much better now, but, I know like when we, you saw me, you know, that was a few years ago, so I’d been teaching then by almost twenty years. So, yeah, I love teaching. I am currently hosting online classes, mentoring other professionals that are out there, and I plan to continue teaching, because seriously, I could not be where I am today without those other professionals that took the time to show their skills, open up the doors, show ways of thinking where I am, to their ideas, and share those with students. So, yeah, I think that’s why museums for me are very important as well.

Throughout your career, what’s the most important piece of advice you could offer a struggling art student?

Wow. Uh, be prolific. Just don’t stop. Make art, be passionate about it, make art around things you like… tell stories about things you like. And eventually you’ll either find your place where you can make that work as a career or other people will see what you do and bring what you do into what they want to do and merge those two together. So I think it’s just – don’t stop. Don’t be hindered by technical problems. Like I said, I couldn’t draw people very well – I kind of faked it, and I still fake it even now… So it’s… just don’t feel impeded, just do it, just do it, just feel… embrace the clumsiness. I think that’s it. And just like, don’t feel the pressures of other people’s expectations.

Looking back, what artworks that you’ve created are you most proud of?

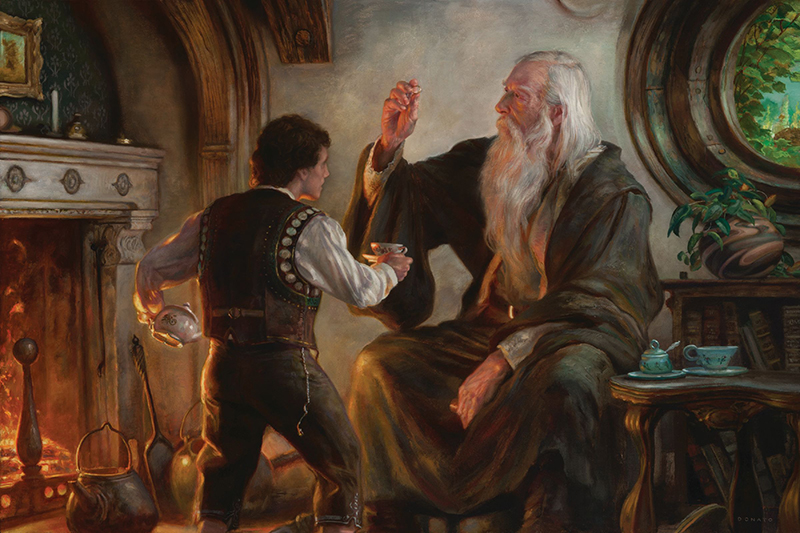

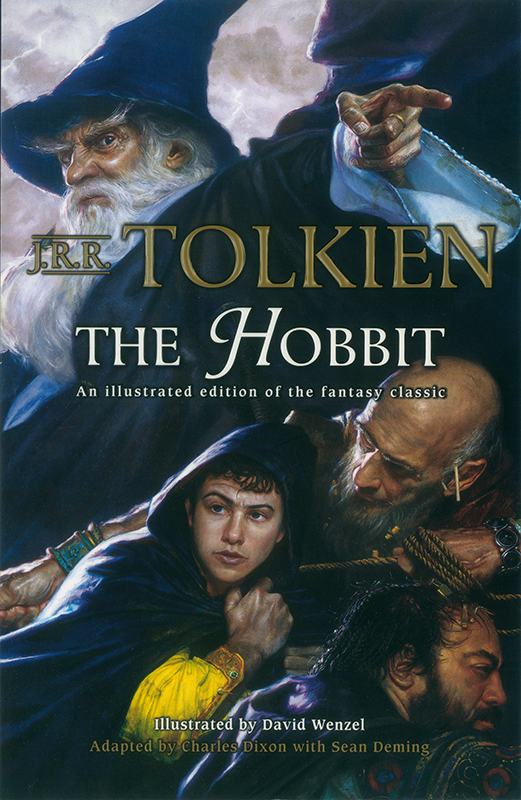

There are quite a few that would sit up there. Mostly the… I think the pieces for me that resonate deep are those that speak to that idea of storytelling, but also of compassion between characters. So there’s a graphic novel cover to The Hobbit that I created about twenty years ago. And, you know, like I mentioned to you, like, Tolkien does… it’s not about the battles and a big conflict. So what I chose for that cover was Gandalf and Bilbo and the hobbits, as they’re all kind of huddled together, working their way through the Misty Mountains, during the rainstorm, with the stone giants off in the distance. So it wasn’t a very climactic… it’s not even a climactic moment. It’s just the drudgery of, like, trying to survive. It’s raining, it’s horrible, it’s nasty, and… but it’s human, right? That’s what… like everyone knows that experience of getting caught in a rainstorm, right? I’m sure you do, right? So… I wanted to have you empathize with Bilbo, what it felt like to go out into the big, big world and see new things. So that’s, that’s one of them. That’s… so, yeah, that’s the ideas.

So you’ve been in a number of exhibits, you’ve got, you know, you’ve won countless awards, and accolades from your peers. When I was at Illuxcon, you were just swarmed by students and artists and you were just so humble. You were kind of taking time with each person, giving them a piece of your time. So what keeps you that way? What makes you humble after winning so many awards?

Well, I’m not in it for the awards. I mean, the awards are, like, very nice, they’re gracious, and I appreciate them, but the reason why I make my art is not to win an award. The awards come from people’s judgment, external judgment of what I’m doing. And again, it goes back to, like I mentioned about teaching, like the idea of… someone gave up their own passion to spend time in the studio to share like a teacher, like to share their ideas, to take time out, to slowly explain things. And I feel like I have a responsibility to give that back and give that… pass that on to another generation of artists and illustrators – you know, storytellers who want to do the same with their own ideas, with their ideas, with their visions. So I think what I am very much aware of is that I am just one in a lineage of storytellers. Like I am here today because of the storytellers like Rockwell, the storytellers like J.R.R. Tolkien, right? Who shared their passion and passed along their knowledge. And so it’s… I’m hoping that somebody after me, some student that may be, or some other artist that, you know, that gets influenced by walking into the Norman Rockwell, like seeing the show, Enchanted… might be a future illustrator, a future storyteller… and that’s all I need to be happy with. That’s my part.

Well, that’s all the time we have Donato. Thank you for joining us. For more information, check out Donatoarts.com and our own websites, nrm.org, illustrationhistory.org, and visit the Rockwell Center for American Studies at rockwell hyphen center.org. As always, don’t forget to subscribe to be notified of the latest content, and this has been a production of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

VIDEO

IMAGE GALLERY

1. Photograph of Donato Giancola, n.d.

2. Donato Giancola, Archangel, 1999

3. Donato Giancola, Daenerys Targaryen – Mother of Dragons, 2014

4. Rembrandt, The Storm on the Sea of Galilee, 1633

5. Donato Giancola, Bag End: Shadows of the Past, 2013

6. Donato Giancola, The Taming of Smeagol, 2010

6. Donato Giancola, The Taming of Smeagol, 2010

8. Book cover for Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration, 2020

9. Guglielmo Cortese, St. Michael Vanquishing Lucifer, 17th Century

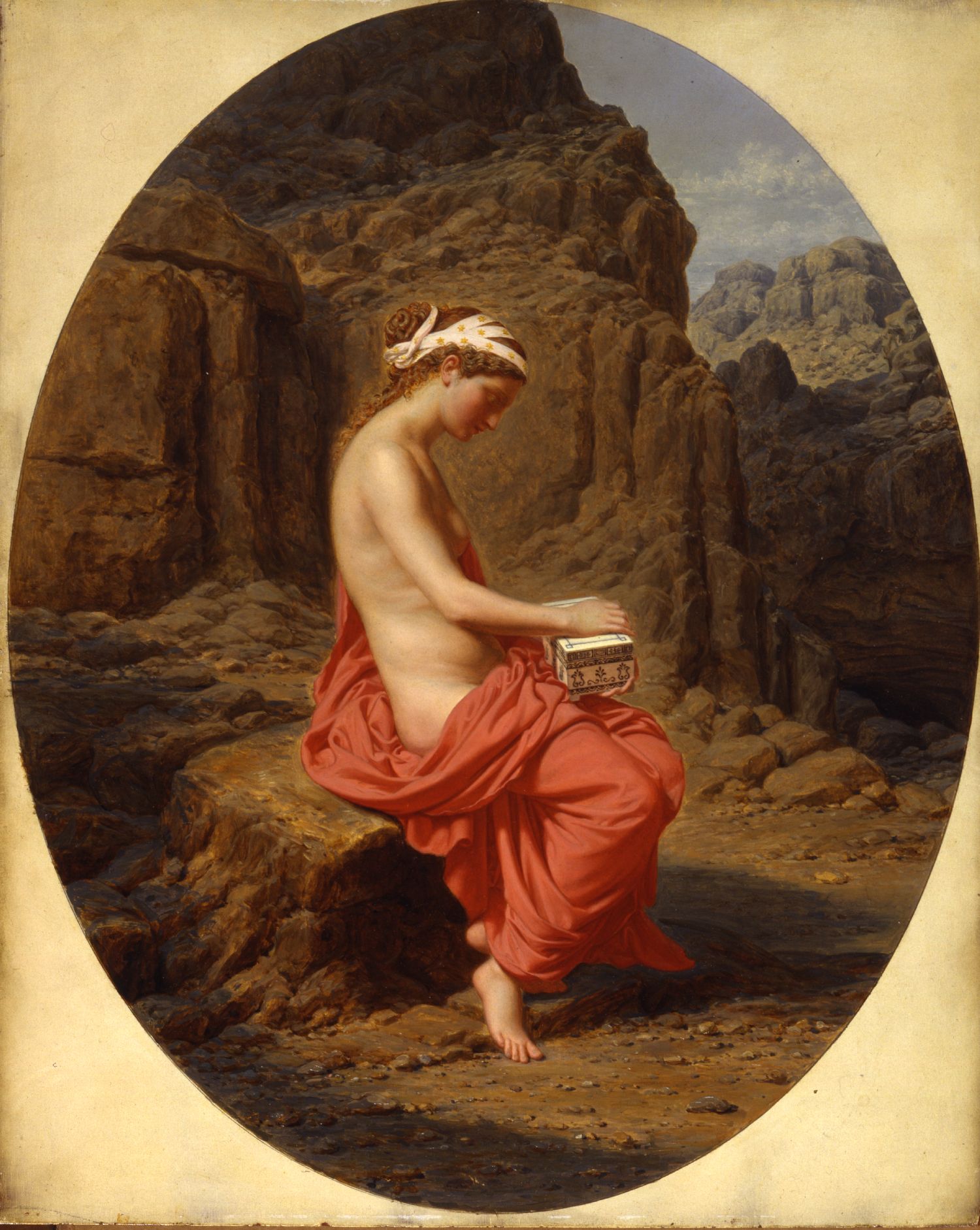

10. Willem van Mieris, Apollo Slaying the Python, 1690

11. Bertha Corson Day, Perseus, 1902

12. Syrian, Relief with Two Heroes, tenth–ninth century BCE

13. Raphael, Saint George and the Dragon, 1504-1506

14. Bernat Martorell, Saint George and the Dragon, 1434/35

15. Donato Giancola, Dungeon Map, ca.1985

16. Donato Giancola, Frost Giants, 1985

17. Donato Giancola, The Hobbit: Expulsion, 2000

18. Caravaggio, The Taking of Christ, 1602

19. Bosch – Garden of Earthly Delights

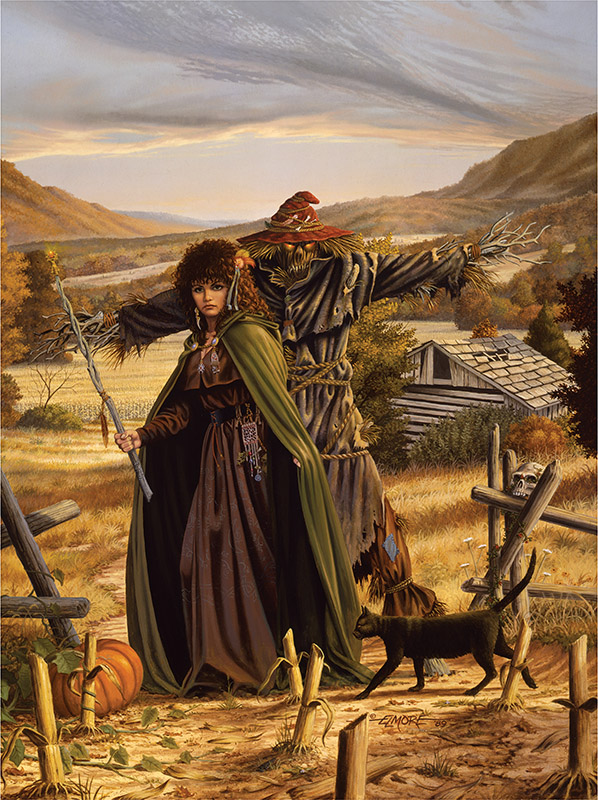

20. Jeff Easley, The Big Red Dragon, 1991

20. Jeff Easley, The Big Red Dragon, 1991

22. David C. Sutherland III, Cover illustration for the first Dungeons & Dragons Basic Set, 1977

23. David C. Sutherland III, A Paladin in Hell, 1978

24. Donato Giancola, Game of Mind, 2006

24. Donato Giancola, Game of Mind, 2006

26. Gustave Doré, “‘Oh, granny, your teeth are tremendous in size!‘ ‘They’re to eat you!’—and he ate her,” 1865

27. Donato Giancola, Beren and Luthien in the Court of Thingol and Melian, 2015

28. Donato Giancola, St. George and the Dragon, 2010

29. Donato Giancola, Source photographs for St. George and the Dragon, ca.2010

29. Donato Giancola, Source photographs for St. George and the Dragon, ca.2010

29. Donato Giancola, Source photographs for St. George and the Dragon, ca.2010

30. Tara Larsen Chang, Donato Giancola, 2014

31. John William Waterhouse, Hylas and the Nymphs, 1896

32. John William Waterhouse, Tristan and Isolde with the Potion, ca.1916

33. Book cover for J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, 2001

34. Donato Giancola, The Hobbit: Expulsion, 2000

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration explores fantasy archetypes from the Middle Ages to today. The exhibition will present the immutable concepts of mythology, fairy tales, fables, good versus evil, and heroes and villains through paintings, etchings, drawings, and digital art created by artists from long ago to illustrators working today.

The exhibition Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration is organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA, and will be on view here from June 12 through October 31, 2021.