Episode 14: Etienne Delessert

Jesse Kowalski:

Welcome to The Illustrator’s Studio. I am Jesse Kowalski, Curator of Exhibitions at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. The Illustrator’s Studio is a weekly interview series, a project of the Museum’s Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies.

Jesse Kowalski:

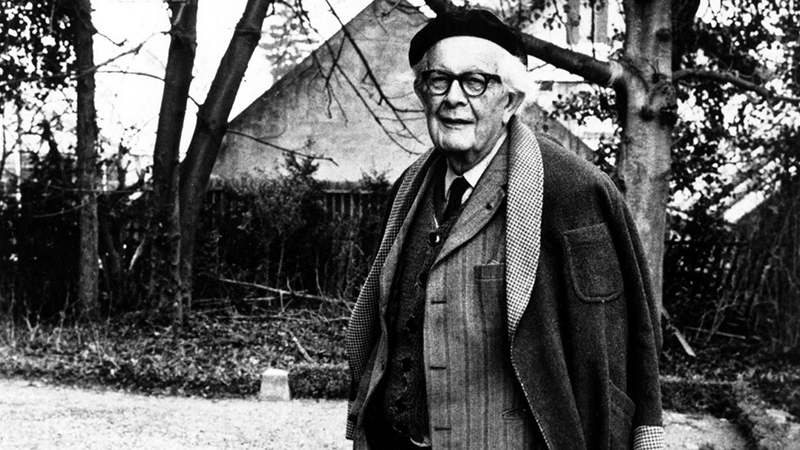

In this episode of The Illustrator’s Studio, we welcome Etienne Delessert. An award-winning illustrator, Swiss-born Delessert moved to Paris at the age of 21 to pursue a career as an art director for magazines and advertising agencies. Just a few years later he emigrated to the United States and quickly found work creating art for magazines and children’s books. Since that time, he has illustrated more than 80 books, created several animated shorts for Sesame Street, has had his artwork exhibited in several countries, and has been awarded 13 gold and 14 silver medals from the American Society of Illustrators. And if that wasn’t enough, he recently formed a foundation for picture book art in Switzerland. Welcome, Etienne.

Etienne Delessert:

Hello. Thank you for having me.

Jesse Kowalski:

Sure. In your work you use elements of fantasy and caricature in a style that’s very distinct, and I wondered, how would you classify your style?

Etienne Delessert:

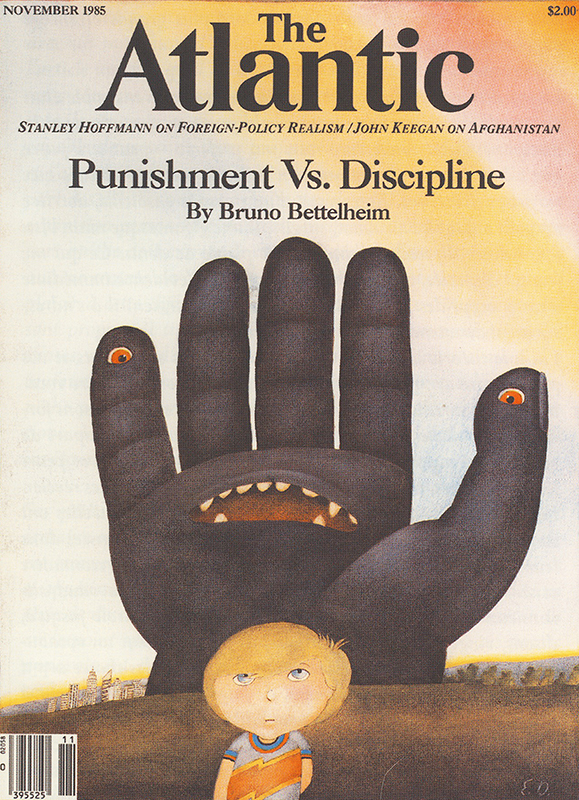

Well as you mentioned I have done books, but also paintings. So I worked for the press, for the New York Times or The Atlantic magazine. I did many cover stories for them. And so I would say I adapt to the venue somehow. But I would say that my style is to transform reality with imagination. I would say I’m closer to… Well I love beautiful paintings and artwork, but I’m closer to writers I would say.

Etienne Delessert:

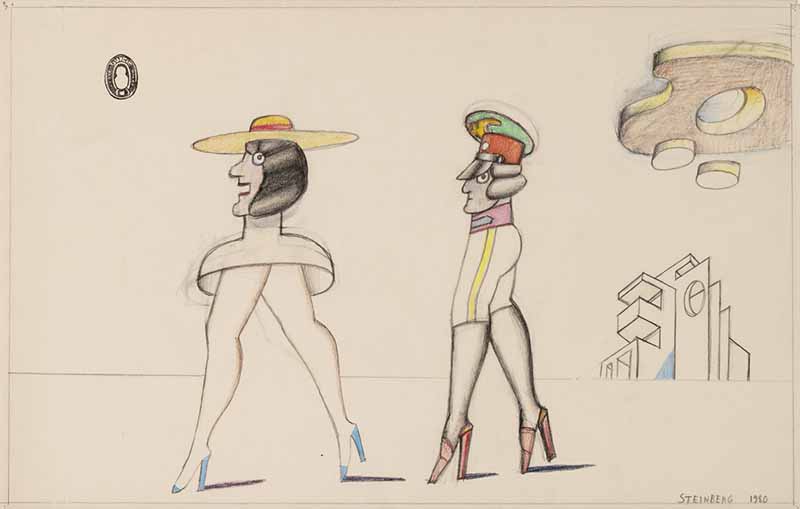

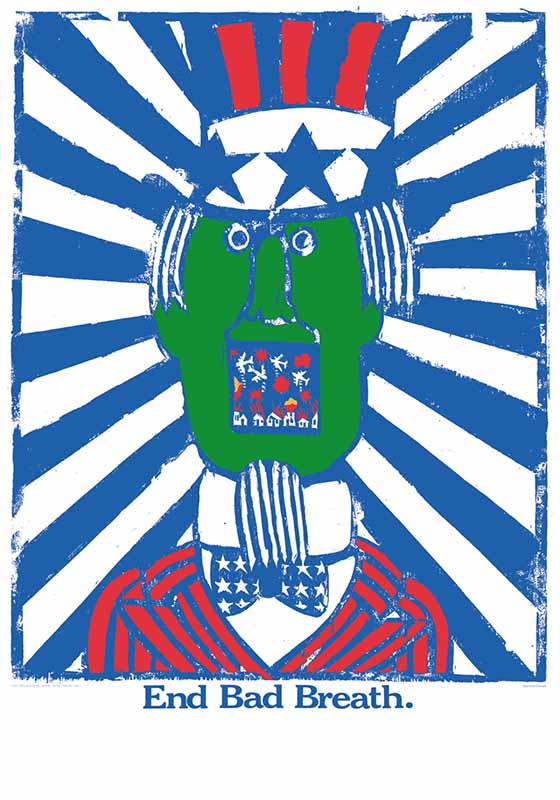

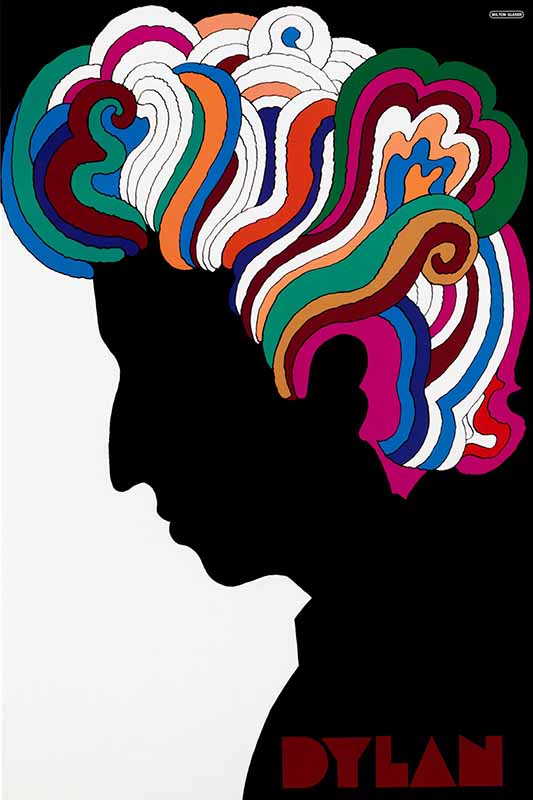

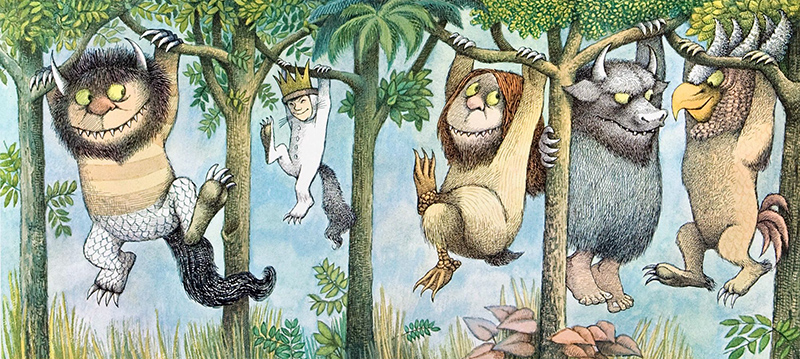

And that’s, for the last 50 years, a direction that was taken by some great graphic artists in Europe and in the States, I would say. Evidently, I admire Steinberg. I would name him, and Glaser, and Chwast of the Pushpin, here in the States. In France, Andre Francois, or Alain Le Foll. And evidently, for books, Sendak and Tomi Ungerer.

Etienne Delessert:

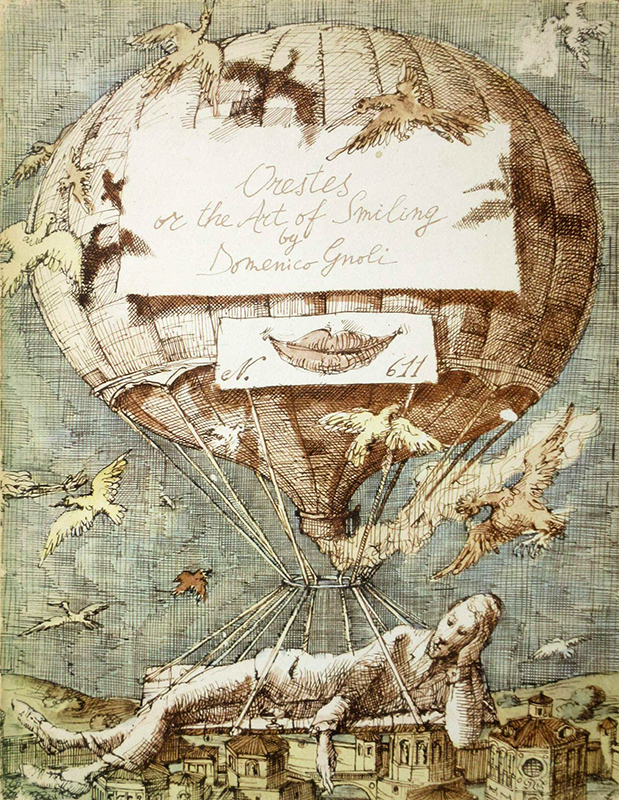

And someone which people don’t really know, but was great. Someone called Domenico Gnoli, who died when he was 36 in 1970 after having done two picture books, one of them Orestes or the Art of Smiling. And he did incredible, beautifully drawn reportage for magazines like Fortune, or Holiday at the time. And he’s known more now for the large paintings in the last part of his life that were details of clothing: shirts, buttons, which are great. I prefer the loose drawings of corridas. But I have to name him because I would say he was one of the reasons for me to come to New York in ’65.

Jesse Kowalski:

Yeah, I was very interested to learn about your experiences with childhood development and your work with the child psychologist, Jean Piaget. Could you talk about that a little bit?

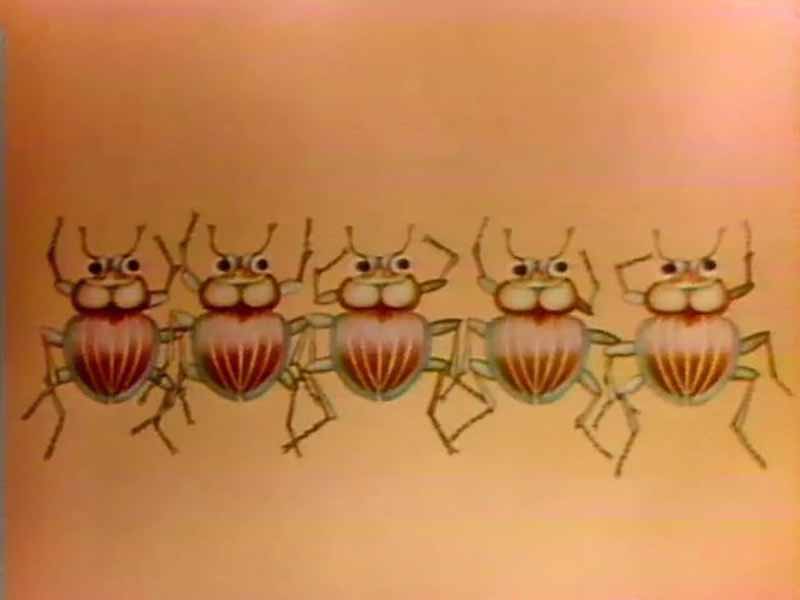

Etienne Delessert:

Well, two things. My childhood was, unlike Sendak, very normal and very happy. I was living in Lausanne, Switzerland and I was going to the countryside with my parents many times. And I would spend summers near Lausanne in the countryside in an incredible garden, which I call the Garden of Eden, and where I would learn everything about flowers, birds, bugs, little animals. And I remember that in this… This really influenced my vision as an artist in a way that I have the rhythm of the human geometry of the roofs of the farms in my blood.

Etienne Delessert:

And also I remember that my father would be able to sit for an hour in a forest, for a picnic, and have a mouse coming to eat in his hand. I mean he was really taming little animals, and big monsters as well. He was a very, very liberal minister, Protestant minister. And Protestant ministers have a very different way of seeing the world than American Protestants. And so I had a very happy childhood, going through learning Greek and Latin and German, and being kind of bored in school. And when I was 18 I decided not to go to a university.

Etienne Delessert:

My father wanted me to be, or would have wished that I would be a diplomat. And my wife, Rita Marshall, the great art director, is laughing at me when I mention that memory of being a diplomat. She says, “Well, you are too brutal.” Which, I think great diplomats have to be brutal once in a while just to assert their position. But I decided at 18 I would stop my very classical studies and I would go to a graphic design studio.

Etienne Delessert:

And I told that to my father and my mother separately. And each one of them had very exact, very similar answer. They say, “Well, we know you well enough to know that if you choose that career you’ll do it well.” And I had no problem at all with them, changing completely the course of my life and going to a graphic design studio, doing design advertising. And it was a great apprenticeship.

Etienne Delessert:

When I was 19 I entered the studio. And I had my own clients, which was a publishing house, and I was the art director of their books. And long days, 14 hour every day, working on my… in the studio and for my own stuff. And I moved to Paris when I was 21. I was not drawing. And that’s a question that people will say, “When we see what you do, you must have been drawing all your life.” No, not true. I started when I was 20… 23.

Etienne Delessert:

And I worked as a graphic designer and freelance art director for large advertising agencies, designed magazines, and then decided I want… since I am a storyteller, that’s something which is a characteristic of my work probably. And I want to do the picture books. At the time they were very… I mean, compared to, what the production of millions and millions and billions of books today, there were a few books being done. And maybe with more spirit than what we can see now.

Etienne Delessert:

And I decided I’d learn about Sendak and Ungerer and, again, Domenico Gnoli, and the Pushpin, evidently. When I was in Paris and there was an American bookstore, I could see magazines and I could see books there. And I came to the States to do books, which took some time. It took me a year.

Etienne Delessert:

A fun story. I’d been introduced by Tomi Ungerer to Ursula Nordstrom, the famous “monster,” looking like Orson Welles in A Man of All Seasons. And she received me very nicely. We spent an hour. And I couldn’t speak basically a word of English at the time. But we met for an hour, and she say, “Okay, I’m going to call Tomi to thank him. And I’ll have a manuscript within weeks for you.” And it was heaven. I mean, it was really the idea of working with a great editor.

Etienne Delessert:

And I was leaving the room and opening the door when she said, “Oh, by the way, are you doing hand separations?” And I say, “Yes, I’ve done a few for book covers. But I want my very first picture book to be in full color.” And she say, “Well you know, Tomi and Sendak are still doing hand separations, and so you should be ready for that way of working.” And I said, “Well I’m sorry. My first book will be in full color.” We never spoke again. And that was one of the very big, stupid mistakes I made in my life. When you are young you feel you can convince other people with more power than you have.

Etienne Delessert:

So I was very interested in picture books. Why? And you mentioned Piaget. Because I feel that when… At least in my case, when I remember my youth, I would say that I had a great stepmother. My mother died when I was born. And she was a great storyteller. And we would do something that few people do, and maybe psychoanalysts should recommend to parents who have difficult children, it’s to invent plays. I mean you take a subject, and for half an hour you play the different characters of the story you are going to tell. And my mother would leave me by myself on the couch and go to the kitchen, leave the door half open, and listen to and sometimes laugh out loud to what I was saying. But I was able to go on telling my own stories already when I was, I don’t know, five, six, seven.

Etienne Delessert:

And I love the idea that an adult can try to remember the emotions, the fantasy, the dreams. I mean, when you are challenged, first you know you don’t know much. That’s the one thing, if you are clever. But also you realize that many things maybe are possible. And that’s a cliche, but it’s true. I mean, as an adult, you are confined in other people’s ideas and other people’s jobs and social relationships. So that’s why I loved picture books.

Etienne Delessert:

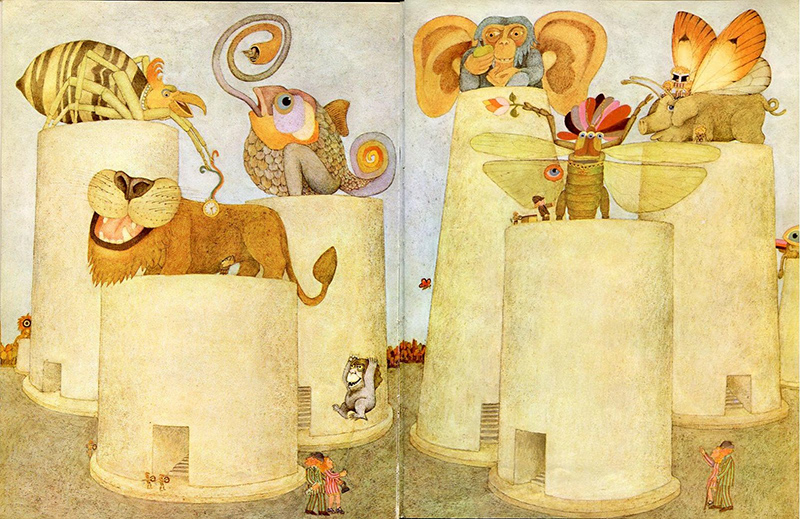

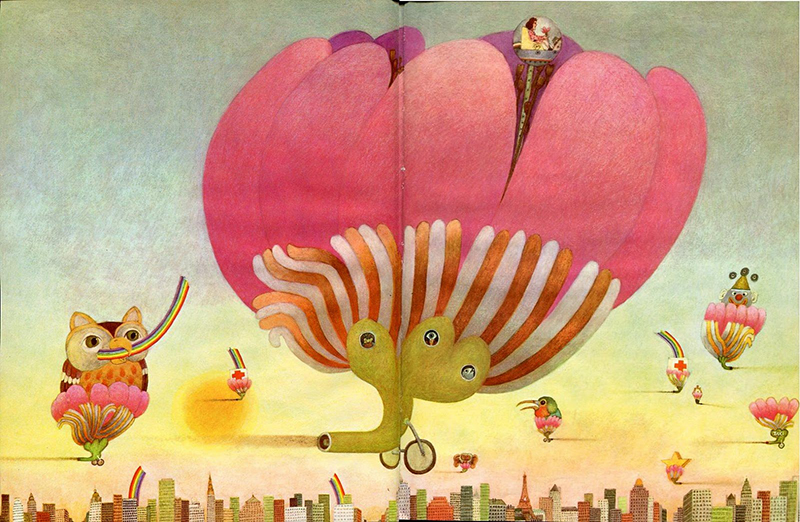

And also they are cheaper than to do a film, somehow. I experienced that, and when I was doing animation. And so my first books were done with a small publisher called Harlin Quist. And he was kind of a Don Quixote of publishing. They were doing daring things that other larger publishing wouldn’t do.

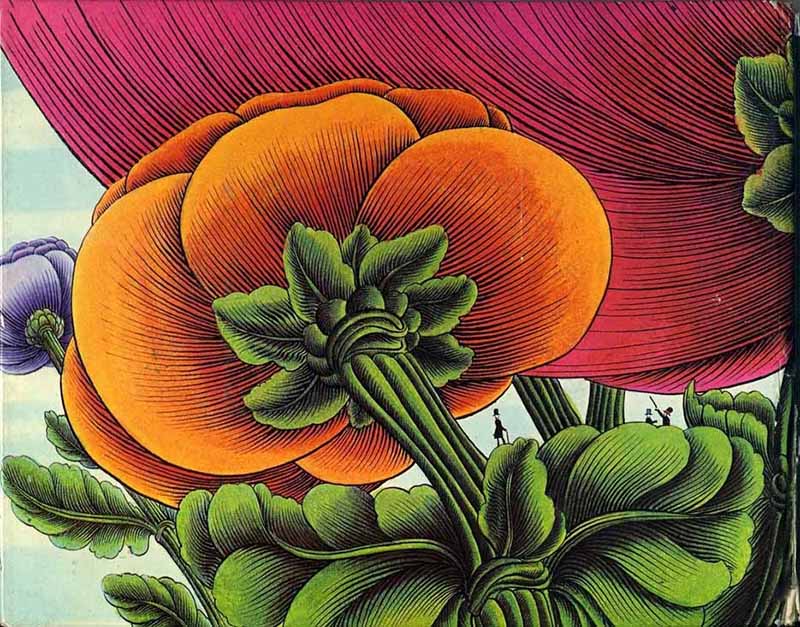

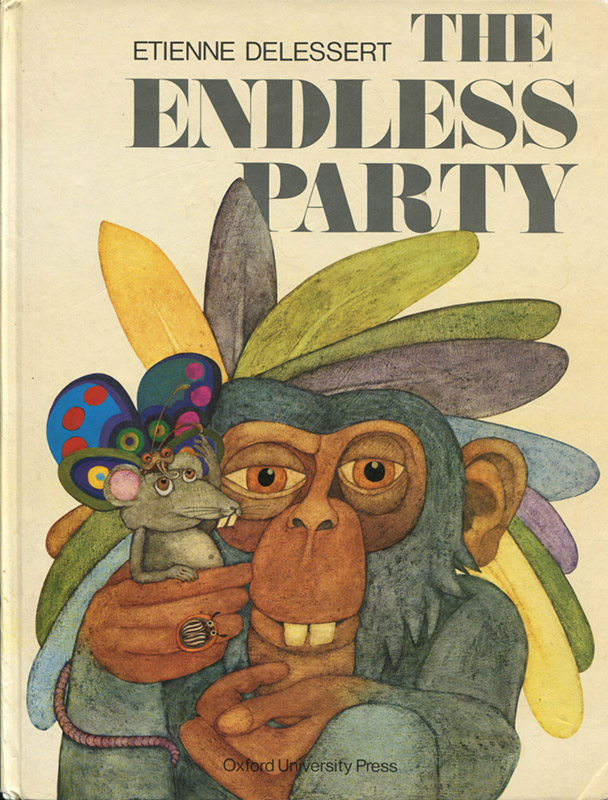

Etienne Delessert:

And so my very first book was called The Endless Party. I did it in New York when I came in 1965. I was 24. And I worked on that Endless Party, which is a story of Noah’s ark, very like. Noah is inviting animals on the beach for a big party. And I have no presence of God at all in the story. It’s just a big cruise somehow. And the animals go on the ark, they play games, get bored, take over. They become pirates on the boat. And it ends well.

Etienne Delessert:

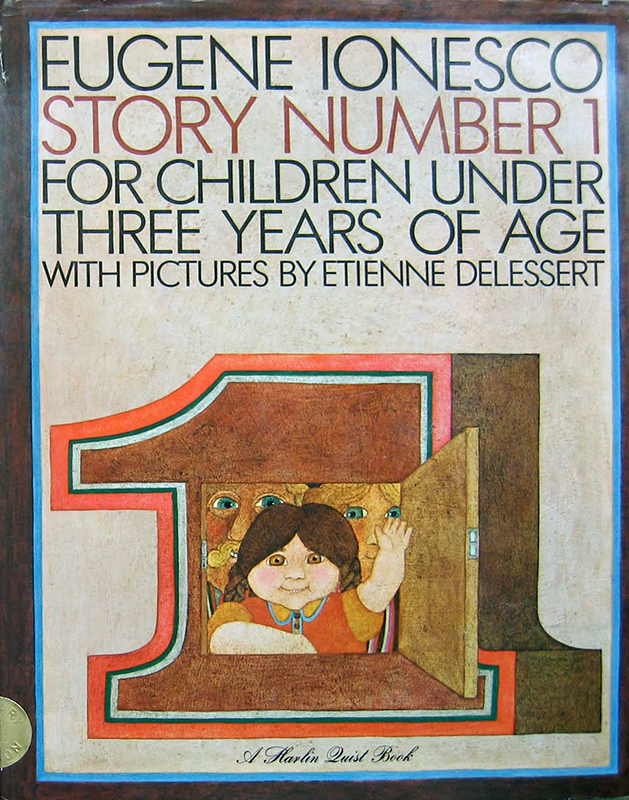

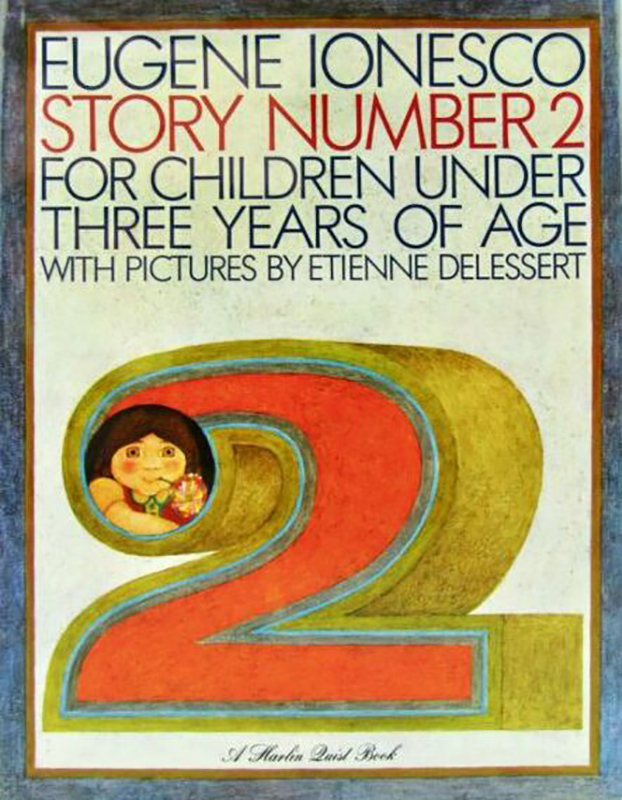

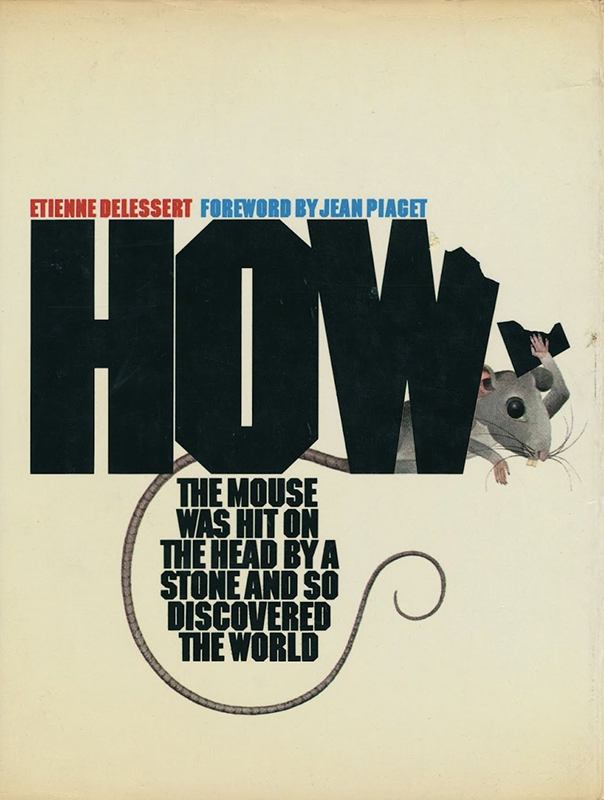

Anyway, this and two books I did with the great playwright Eugene Ionesco, Story Number 1 and Story Number 2, were very, very successful. They had many translations and many reprints, and it was great launching somehow. But also people said, “Well, these are not books for children.” And that made me kind of enraged because I, well, I questioned myself. And, by chance, there was the piece in 1970 in the New York Times Magazine about Jean Piaget, who was a Swiss psychologist, or etymologist I would say. And working with children to understand adults. That was really the line.

Etienne Delessert:

And I say, “Oh, great.” I didn’t know him at all. But I say, “He is Swiss. I’m Swiss. Let’s go to Geneva and ask him if my books are really wrong, I mean if I don’t speak for children, somehow.” So we met. And he told me first he needed time to look at the books to answer my questions. But what would have been, I felt, a 30 minute visit lasted for hours. And we got along really well, at my big surprise.

Etienne Delessert:

And at the end of the day, he said, “You know, I’ve studied so many time drawings by children, but I never thought about wondering how children read adults’ pictures. So can we work together?” That was the way we started eight months of collaboration in Switzerland, studying with children in Swiss classes and with a team of his assistants.

Etienne Delessert:

I would meet him every 10 days or so in his garden and talk about the work we had done. And about plants, exotic plants, plants that he wanted to grow in Geneva, without much success, in his garden. And we should remember the importance of this collaboration for me because in the year 2000, when Time magazine had a special issue about the giants of the last century in the field of psychology, they had two great names, which were Freud and Piaget.

Etienne Delessert:

And so it was such an easy collaboration, because we were coming from such a different point of view, somehow, or past. And when I showed him all the drawings, at the very end, he said, “Well everything is fine, and I agree with it.” And, in a shy way, he said, “Can I write a forward for it, for the book?” And evidently it was great news.

Etienne Delessert:

And what we did was, I had written a story line, and if I showed to kids without saying, “My own sketches,” they would have to do their own interpretation of my story. And I would show my sketches, and they had to write the story without seeing the storyline, my storyline. And we were very surprised because many times, quite a few times, the drawings of the children, who were five at the time, trying to explain what the nature of phenomena were: what a cloud is, what the sun, what is shadow, what is thunder, rain, snow, their interpretation, their drawings were very similar to my own sketches. So that was the answer that Piaget gave me, that I was right and I should continue to do books.

Jesse Kowalski:

Okay. And going back to your start in illustration. So you were largely self-taught, correct?

Etienne Delessert:

I am self-taught, yeah. Completely. I never went to a school, art school.

Jesse Kowalski:

So how did you learn to draw? Through books or practice or what?

Etienne Delessert:

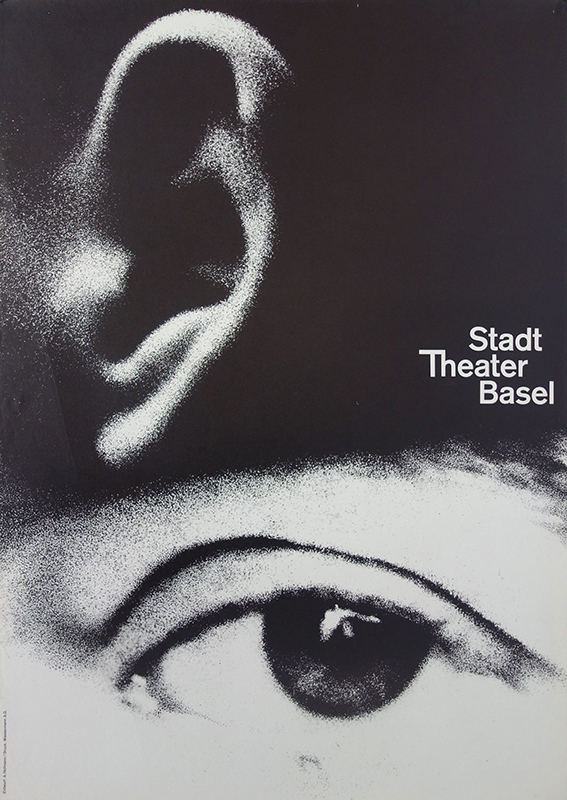

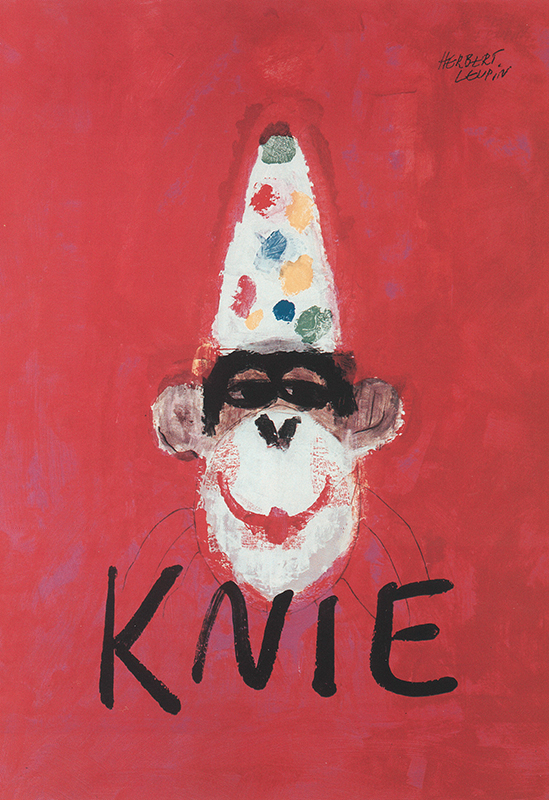

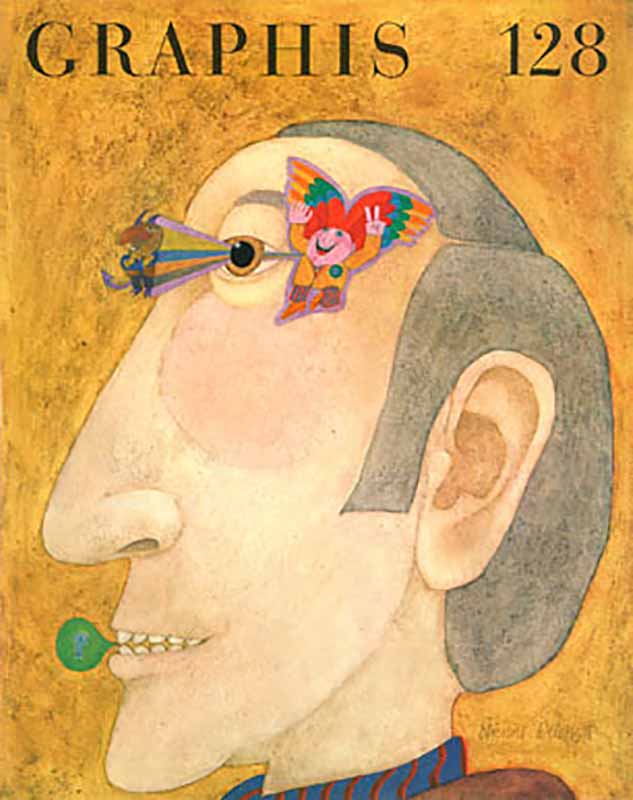

I would say that, when I was 13, 14, I was watching, on the streets of Switzerland, the posters. There are more posters in Switzerland than any place. And I would love the Swiss-German, great graphic design artists, like Hofmann and Muller-Brockmann and [inaudible] Gerstner. And Piatti and Leupin I would say Leupin was my favorite. So I was learning from the street and also from a wonderful magazine that doesn’t exist anymore called Graphis.

Etienne Delessert:

It was published in Zurich by Walter Herdeg, who was a graphic designer as well. And he was the only one at the time, and still now I think, to mix fine art… so-called fine art, we can talk about commercial and fine art these days, with advertising, with comic strip, with cartoon, with photography. It was an incredible bi-monthly magazine that many, many people in the advertising, publishing world and artists were sharing. So when you had a piece on the cover of the magazine or a piece inside of the magazine, you were launched in the world, somehow. I was very lucky to have early a cover and pieces in Graphis magazine.

Etienne Delessert:

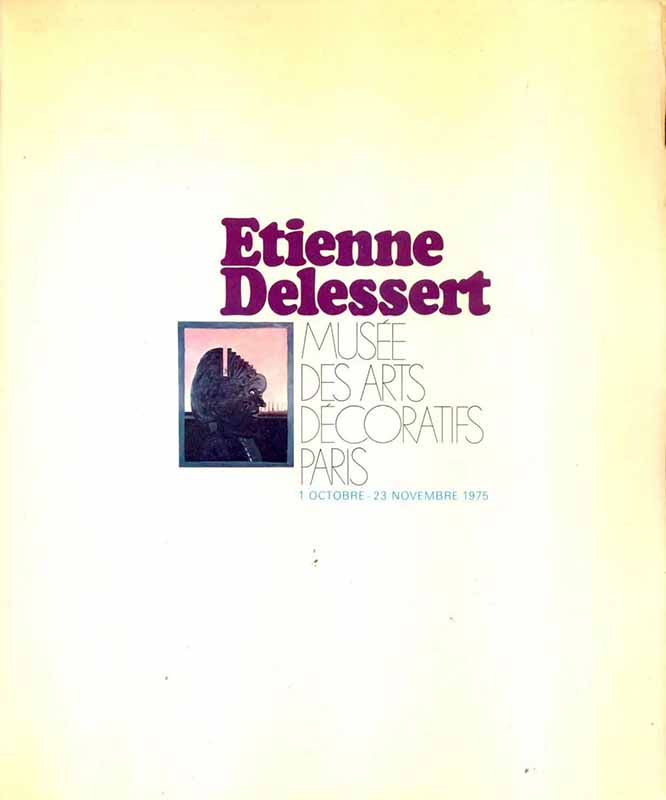

That was my school, and more than museums, more than fine art museums in Switzerland. Some of them are beautiful and great, mostly in the German part of Switzerland. And I would say that, and I experimented that in Paris in ’75 when I was 34, when I had a show in the Louvre, my first retrospective in the Louvre, in The Musée des Arts Décoratifs. That was at the time the Museum of Modern Art in Paris. There was no modern art museum in Paris. And the man who was the head of that museum, Francois Mathey was incredible.

Etienne Delessert:

I don’t know any curator today who would have such a large vision of art, mixing Picassos and Matisse, or Picasso, or Dubuffet, or Hockney. Hockney had his first retrospective just before mine. He was mixing these great artists with graphic artists, with Folon, with Andre Francois, with the Pushpin. They had a show there. And he said, “Well, there are good and bad pictures, nothing else.” And he was very, very interested in what he called graphic artists, because he felt we were in touch with social and political reality much more than the artists that are called fine artists.

Etienne Delessert:

And today I still share that approach in a way that… I feel that fine art is more commercial these days than many illustration can be. The word “commercial” art for Rockwell or for Steinberg or for the great artists and illustrators is totally wrong. It’s still in the mind of galleries and museums. It’s changing, it’s changing. And the reason I created my Maitres de l’Imaginaire, in French, which is Masters of Imagination Foundation, is to collect originals of some of the best artists, who have done picture books but not only, and to place them in great places, in great museums and show them and document and archive them.

Jesse Kowalski:

When did you get started in animation as a serious…

Etienne Delessert:

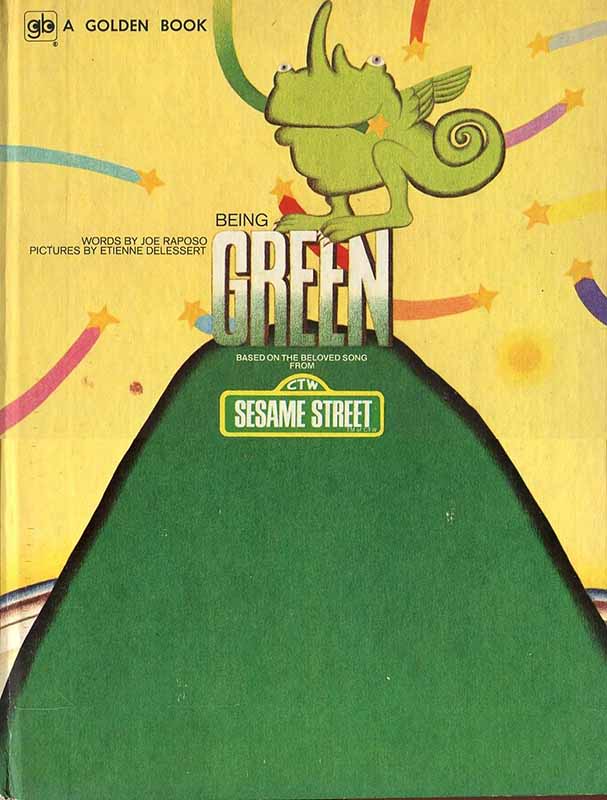

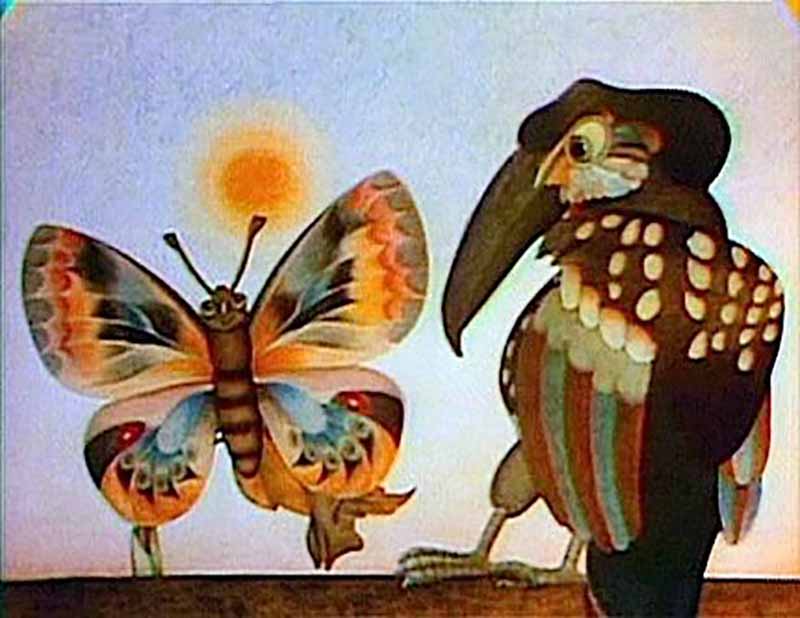

Doing animation? Well I had done a book with Sesame Street called Being Green, by Joe Raposo, who was their music director. And at that time I was able to do, I think, the only book for Sesame Street that doesn’t use the Muppets, which I loved. I love the Muppets. I loved the Muppets. And one of my regrets in my career is not to have been associated closer to Sesame Street. If it had been a different kind of life. And one of my characters called Yok-Yok almost came to Sesame Street.

Etienne Delessert:

Jon Stone, who was the original producer of the show, who decided of the format of short sequences, had come to Switzerland and loved the little films I was doing with that character, for the Swiss and French TV. And said, “Oh, I want that on Sesame Street.” It would have been the very, very first time that they would have bought something outside of their program. They asked me to do, and I wanted to do, animation. So it was a way to communicate in a different way.

Etienne Delessert:

And I did quite… I mean, depending of the budget, I did some intricate paper cut out animation, which was one of the traditional ways of doing animation. And I did Being Green, like I mentioned, with my own characters and completely with no Muppets, no reference to the program. And it was a huge success, the book. And after that I did some advertising, some medical films, ecological, and environmental films as well.

Jesse Kowalski:

Looking back, what artwork or work that you’ve done, are you most proud of?

Etienne Delessert:

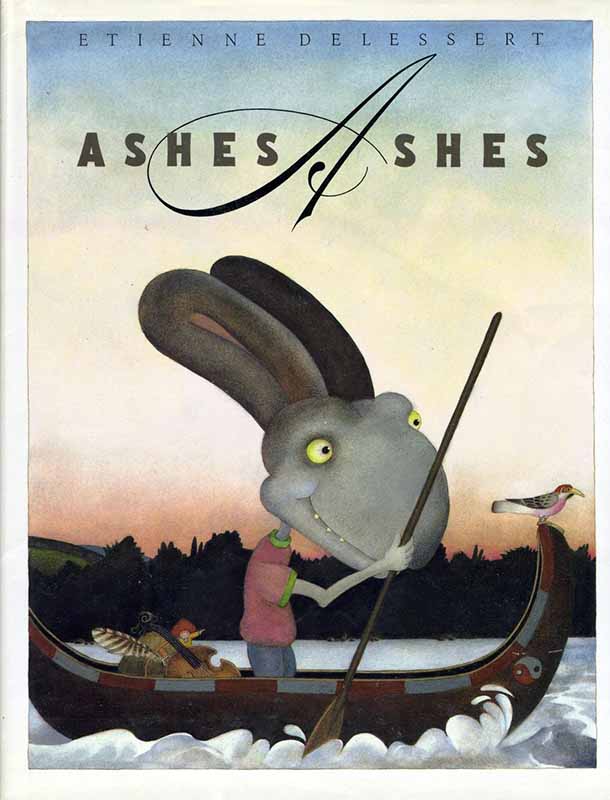

Well in books there is one book I really like, called Ashes, Ashes. Which is a story of someone coming, like in Stravinsky’s and Ramuz’s story of the soldier, he’s coming back home after being far away at war. And he’s coming to New England. And he’s accepting to be invited by three strange characters to go to a new country and start his life in exile, or as an immigrant in a new land, or country. And you realize soon that he’s not the only one to be there. And with a group of friends, they realize that they do the same mistakes they were doing before moving to the new country. Ashes, Ashes. That’s my best book, I think.

Jesse Kowalski:

I just wanted to ask you one last question. You’ve received numerous awards, bestowed by arts organizations and your colleagues. And I was wondering now, why do you think that your work resonates so well among others?

Etienne Delessert:

Well, I’ve been honored in the States by my peers, which was very grateful. And so that was one reason to be proud of it.

Jesse Kowalski:

All right well that’s all the time we have for now, Etienne. Thank you for joining us today.

Etienne Delessert:

Thank you for having me.

Jesse Kowalski:

For more information check out the Etienne’s website at etiennedelessert.com, and our own websites, nrm.org, illustrationhistory.org, and visit the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies at rockwellcenter.org. As always, don’t forget to subscribe to be notified for the latest content. This has been a production of the Norman Rockwell Museum.

Jesse Kowalski:

To watch the video of this podcast, or to see the images referenced in this episode, please visit nrm.org/podcast. New episodes from The Illustrator’s Studio are released every Monday. For questions or comments, please email us at podcast@nrm.org.