Episode 10: Frank Miller and Tony DiTerlizzi

Boris: Welcome, first panel of the day for everybody here I hope. Thank you for coming. We have an amazing lineup of two great, great artists, which I’ll be introducing and bringing them on stage right now. First up, we have Frank Miller there, legendary creator of Sin City, and 300 and Batman and The Dark Knight Returns.

Frank Miller: Good to be here.

Boris: Next up is the award winning children’s writer and children’s book author and artist, Tony DiTerlizzi.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That’s good. We got the memo. See the black jacket and we both got our Converse.

Frank Miller: Pretty awesome. Mine are nicer than his.

Tony DiTerlizzi: I just got to get a couple more movies made and then maybe I’ll get a nicer pair of Converse.

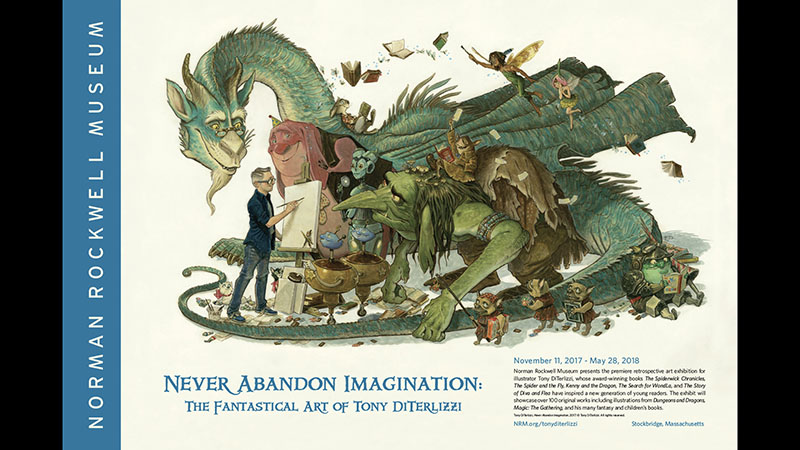

Boris: First up we have… So both of these gentlemen are going to be having exhibitions at the Norman Rockwell Museum, and we have a video to play from the Norman Rockwell museum.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Being in an artistic household, my parents would buy different art books all of us DiTerlizzi kids had to share. And we had a few books that were highly coveted. One was Harry Abrams created this giant collection of Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers. And that was a fantastic book. My dad and mom had taken the famous artist course when they were younger that Rockwell was a part of. So Rockwell was definitely a big part of growing up in our household.

My mom also bought us Brian Froud anomalous Faeries book in the late seventies. And that just blew my mind. Having a retrospect at not even 50 years old at the Norman Rockwell museum is a huge success to me. It’s very meaningful to me. I grew up copying his drawings and looking at that and wishing I could be an illustrator like him. So to have a collection of my drawings from the beginning of my career to where I am now is an incredible milestone.

It’s very meaningful to me to be able to have my work hanging alongside these paintings that are iconic now. Legendary. When I think of illustrator I think of his work and the idea of wanting to be someone who’s remembered in that way. That all this artwork that I’m creating, these stories I’m telling, don’t disappear when I disappear. That they live on.

This is an incredible achievement for me. I thought 70 year old Tony might get to see this. So the idea of 40 something Tony getting to see this is… I’m waiting for my mom to wake me up and I’m still in seventh grade and awkward and playing Dungeons and Dragons. And no one understands me. And this is a very much a dream come true for me. Man, my head is fat. The thing is just like a water balloon, Frank.

Boris: So you both will be having your works shown in that museum. You’re later this year and then you’re probably the year after. What was it about a Norman Rockwell that you guys looked up to?

Frank Miller: Norman Rockwell, first, just as an illustrator he was outstanding. He was world-class in every sense. And just as someone who spent his whole career drawing and composing pictures and all of that, it’s wonderful to see a master at work. Beyond that, Rockwell had a way of capturing the essence of his country and his people in his time. It was with deep affection and with great care.

Now, like most artists, he’s known for the things that he did that have become cliches. They become cliches because they’ve been imitated so much. But when he did them they were fresh and original and they still are when you look at his work. But to actually visit his museum, or even to just look at a book of his work, you see a much wider breadth of, you see the scale and the scope of what he did.

Of course, going to the museum, also, you get to see the methods he worked in. And they’re fascinating, because as a practitioner I particularly enjoy looking at the other guy’s tricks. And like any good artist he used every trick in the book.

Tony DiTerlizzi: It’s interesting because I think both you and I use story and pages to tell our stories and reveal it. And the mastery of Rockwell is he does it in one image. He tells an entire story through props and models, body language. And the fact that he kept that going month after month for those covers is pretty amazing.

I always thought, actually, that he depicted a happier America through really horrible, the Great Depression, going into the war. And yet he’s depicting what we consider like saccharin images, but I think he’s intentionally doing this to raise our hopes.

Frank Miller: Well, keep in mind that what was going on in American cinema at the time was very buoyant, optimistic, movies were coming out during a time of war, of world war.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah.

Frank Miller: And so at that period entertainers and artists took it very much as their duty to lift people’s spirits and to give them hope.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Well, we need it now more than ever.

Boris: But a lot of artists are the hoity-toity crowd. Didn’t take Norman Rockwell seriously. But in many ways he’s outlasted. It’s 70 years later and people are still talking about him.

Frank Miller: As a comic book artist I can sympathize.

Tony DiTerlizzi: And as a kid’s book, “Oh, you do kiddy’s books. Oh that’s so cute.” Yeah, thanks. Thanks for that. “I have an idea for a kid’s book.” Do you know how many decades we had to wait for Mouse to clumber along and get at least the literary hoity-toities to take us seriously?

Frank Miller: It’s amazing how long it takes to change people’s points of view.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah.

Boris: Yeah. It’s the same thing with, like you said, with children’s art. Children’s art goes back hundreds of years and it’s in museums and people still look at it as a bit of a downgrade because you’re not in the New York art scene.

Frank Miller: Tony and I have conversations whenever we meet about artists like Tenniel and Arthur Rackham and other people whose names are unrecognized by most of the public, but who are real legends in illustration. And I think there just became this bizarre division that, I don’t know if it started in England or in America, of separating illustration into adult and children’s categories.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah. And yet the interesting thing is when we’re young, infants, some of our first exposure to art is through books. Here’s a copy of The Very Hungry Caterpillar. I’m going to read you Goodnight Moon. Here’s Dr. Seuss. Here’s Maurice Sendak. For me, that’s not just forming my view of drawing and art and pictures.

And then that dialogue now continues into, if you become a reader and if you love visuals, and you need visuals to understand and comprehend what you’re reading as you’re grasping this super power, frankly, to be able to look at these words on a page and get emotion, that moves into comics. I feel like it all lives in that really important part of the formation of who we are as young people.

Boris: So when you guys were young who are the people that you guys were looking up to and trying to emulate?

Tony DiTerlizzi: Oh wow!

Frank Miller: Jack Kirby, I’d have to say would be the biggest one. And then as time passed by, I discovered Will Eisner when Denis Kitchen started reprinting The Spirit, and many others. But the next big breakthrough for me was when Forbidden Planet opened its doors in New York City and I discovered the world of European comics and Japanese comics. And so that was when I obviously got exposed to Jean Giraud, Moebius. But also jewels like Jacques Tardi, who remains one of my absolute favorite comic book artists.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Speaking of Eisner, I don’t know if I’ve told you this story. When I graduated from art school down in Florida, Will Eisner was teaching a class. So I took this class thinking either I could learn to do comics or what I’d glean from the way comic artists think would be incredible. And it was me, one other artist, and about 20 comic book collectors in this class.

And Will would be at the easel going, “Now when I drew The Spirit,” and he’d rip it off. And then, “But when I drew this one,” and he’d rip it off. And at the end of the class they would just [crosstalk 00:10:39]. So we had to bring in three comic book artists that we looked up to. And I brought in popular artists of the 1990s, so in that year. I don’t want to bad mouth anyone, but I can remember him looking at them and going, “Crap, garbage. Oh, Frank Miller, he’s good. I like that guy’s stuff.”

Frank Miller: That’s not what he told me. Actually, I would get together with Will, and the mentors I’ve had have all had a very New York habit of ripping me to pieces. So the first one was Neal Adams, and then there was Will Eisner. And in both cases they would simply look at the work and tell me everything that was wrong with it. After a while I realized not to get my ego too bruised because this man was spending an hour and a half telling me how bad my work was.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Ah, nice.

Frank Miller: There’s a lot of flattering in that.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That’s awesome. I had also-

Frank Miller: But with Will… I’m sorry.

Tony DiTerlizzi: No, no.

Frank Miller: But with Will it also turned into an ongoing dialogue that never ended.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That’s awesome.

Frank Miller: He and I would argue well into the night and we eventually did the book together that was supposed to be me interviewing him. And it ended up being an extended debate, the Eisner Miller book. And for that Charles Brownstein and I went to Florida and stayed near his home and visited him every day. And we taped these long conversations. And it was fascinating to see how it shifted, because at first it was, “Mr. Eisner, sir.” And by the end of it, it was like, “Yeah, you’re crazy.” And we were just throwing lines back and forth. I learned more from that book than anybody who reads it could, I think.

Tony DiTerlizzi: It’s awesome.

Frank Miller: It was amazing.

Tony DiTerlizzi: I have a lot of artists that I talked in the little film with my fat head about Norman Rockwell and Brian Froud, but actually, one of my big heroes I met in fifth grade. So we had to do book reports and we had to do oral book reports. Did you have to do that, oral book reports?

Frank Miller: Oh yeah.

Tony DiTerlizzi: It’s like oral surgery. You just get up there and tell everybody-

Frank Miller: It prepares you for public speaking.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah. I was really bad at it. And we had all these really awesome books on our fifth grade reading list. But for some reason I really struggled with them because there wasn’t a lot of illustrations in them. I loved books with a lot of illustrations and I couldn’t do an oral book report on a comic book. I had to do one on The Phantom Tollbooth or the Hobbit or The Mouse and the Motorcycle. And so I really struggled. My fifth grade teacher’s name was Mr. Strasburger. Strasburger. We called him hamburger, cheeseburger, all the burgers.

Frank Miller: Yeah, it’s like that kind of brilliant wit you have at that age.

Tony DiTerlizzi: So he made a deal with me. He said, because I was that kid that always drew in the back of the class. He’d be at the front of the class talking and I’d just have my head down, just drawing the whole time. And he said, “I’ll tell you what, if you do a drawing from these books, you can’t cut…

PART 1 OF 4 ENDS [00:14:04]

Tony DiTerlizzi: “If you do a drawing from these books, you can’t copy the illustration, you have to actually come up with your own drawings. I’ll give you extra credit.” Somehow when I went back to those books, I wasn’t reading a story, I was actually reading directions or instructions of what I would draw. When I look back on my life, that was a massively pivotal moment in me becoming an illustrator and a reader, so he’s a big hero to me for that.

Boris: Do you still have those pages?

Tony DiTerlizzi: I have some stuff, yeah. My family, there’s a lot of hoarding and things that’s carefully collected. Yeah, I have a lot of stuff from grade school, but when I think back on my life, when you look back at all the highlights in your life, that one is a massive pivotal moment for me.

Boris: Well yeah, that’s a massive formative event in your career. Frank, what kind of formative events did you have in your childhood that made you want to draw and write comics?

Frank Miller: My story’s not nearly as interesting as Tony’s. I grew up reading a lot of them, and would take typing paper and fold it over, and make little comic books out of it. When I was very, very young, when I was about five years old, I told my mother I would be doing comic books for the rest of my life. But I was trying to come up with characters, and I was coming up with bad versions of the Legion of Superheroes, and that sort of thing.

One day she was cooking and she said, “Why don’t you do a comic book about a doughboy?” Meaning of course a fighter pilot. She was however making bread when she said that, so I went, “Yeah, a boy with the powers of dough.” So I made up a character who could get big, he could stretch, but if exposed to heat, he became brittle and would break.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Dude, where is that book?

Frank Miller: I think my dear older brother actually kept that stuff and he’s got it packed away.

Tony DiTerlizzi: The sidekick’s like Icing Man or something.

Frank Miller: You know, I don’t think he had a sidekick, I didn’t get that far.

Tony DiTerlizzi: But he can’t have gluten? That’s like his weakness?

Frank Miller: I was a five year old kid in the early ’60s, do you think I knew what gluten was?

Tony DiTerlizzi: I’m a 40 year old in 2017, I still don’t know what gluten is.

Frank Miller: I don’t know what the hell gluten is.

Boris: But you had experiences later on in life that really kind of influenced your work, like your move from Vermont to New York.

Frank Miller: Yeah.

Boris: How did that affect you and affect your work?

Frank Miller: Well first and foremost, I got to move to a city I’d always dreamed of living in ever since I first fell in love with it, watching the old Kojak TV show and old crime movies that I saw along the way. But New York changed my life in every way, it certainly developed me as an artist. I mean it was a place where I did everything from getting mugged to fall in love. Of course that changes what you do.

Boris: Okay.

Frank Miller: But the main thing that would affect the work directly is that, that’s where I cut my teeth in meeting the professionals, and learning the ropes, and getting the stern tutoring of Neil Adams, and meeting the whole wonderful community of comic book people that was centered in New York in the early ’80s, and particularly around the houses of DC and Marvel. Those were meeting places not just for editorial sessions and so on, that was where all of the freelance artists and writers would come and congregate, and then we’d pack lunches and go into the park and talk shop. That was our social life. It was a wonderful time.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That’s incredible. You know what’s crazy, as you’re telling me that, or telling all of these folks that …

Frank Miller: I wasn’t even talking to you.

Tony DiTerlizzi: I know, you’re right. But I’m thinking it’s the same way in the ’90s, when Angela and I moved to New York.

Frank Miller: Yeah.

Tony DiTerlizzi: It was the same … This amazing center for children’s publishing, and the same thing, you intersected with-

Frank Miller: Well that’s great to hear, that’s great to hear.

Tony DiTerlizzi: You like that?

Frank Miller: Yeah, yeah. I didn’t know. I thought that you children’s publishing people were just all nasty people who hung out in parks and passed candy out to little kids or something.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Do you know how awkward it is when you don’t have a kid and you see the perfect model for your next book, and you’re just like a dude coming up to some family like, “Can I-

Frank Miller: That’s right up there with seeing an absolutely beautiful young woman in the street and wanting to say, “I’ve got a character you’d be perfect for. Would you come to my studio so I can draw you?” Yeah.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Now imagine she’s nine and you’re saying …

Frank Miller: That’d be [inaudible 00:19:39].

Tony DiTerlizzi: Welcome to my world. Bless you.

Boris: Now Frank, you’ve told the story of how you got mugged in New York.

Frank Miller: Oh sure, yeah.

Boris: And that set you on the path to create Dark Knight.

Frank Miller: Yeah.

Boris: Can you share that story, because it’s such an amazing-

Frank Miller: It’s not much of a story, no. I got mugged at knife point and it scared the death out of me. I remember how absolutely helpless I felt and how completely at the mercy, and how much I felt like a slave at that point. The man had complete power over me. Went into a diabolical rage. I was storming around like Charles Bronson for a few days there, and finally I decided that I better turn this into a comic book.

Right around the same time, Dick Giordano at DC Comics said that he wanted to talk to me about Batman, because he said, “I go to these conventions and he’s the most popular character we’ve got, but we can’t sell them. We’re cutting titles. We’re talking about cutting frequency. Have you got any ideas about Batman?” Now, it is heaven when a publishers says, “We’re on the ropes,” because it means the handcuffs are off.

I mulled it over and I came back after a while, and I said, “Yeah, I want to make him impossibly old, he’ll be 50. He’s going to come back, and he’s going to be meaner than ever.” They were, “Great, great, great. That’s perfect.” I said, “He’s going to have a Batmobile that’s like a tank. It’s an urban assault vehicle, and it takes an entire city block.” They went, “Great, great, great.” I said, “Bodies are going to be flying everywhere.” “Great, great, great.” “And I’m getting rid of the yellow circle.” “No.” It’s kind of the wonders of working with trademarked characters.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Oh my gosh, that’s what crossed the line, was the yellow circle.

Frank Miller: I could not remove the yellow circle. I said, “Okay, I’m not removing the yellow circle. But the second chapter, he gets into a bigger fight. He gets all torn to pieces, he vanishes in the Bat cave, he comes back, patches himself up, puts on the old suit, and nobody notices.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Nice.

Frank Miller: Since then, no yellow circle on Batman.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Well done. Well done.

Frank Miller: See, the thing about the yellow circle, there were two things about it that didn’t work. One was why we’re a target if you’re Batman, but the other thing is it took it from being this big square, cool, [inaudible 00:22:44], and turned it into this kind of effeminate little curly Q bat, that it was like, “Oh, there’s Batman.”

Tony DiTerlizzi: Like an old rubber, dangly, Halloween bat?

Frank Miller: Yeah, it just didn’t work.

Tony DiTerlizzi: No, no, no.

Boris: Tony, you obviously probably didn’t get mugged, but …

Tony DiTerlizzi: By Frank, I mean …

Frank Miller: Not yet.

Boris: Did you have some kind of event that really changed and set you maybe to do The Spiderwick Chronicles, or something that inspired you to do the Spider and the Fly? Something kind of like, “Bam.”

Tony DiTerlizzi: I think every author, at least the authors I know, there’s the story you are telling, and then there’s the story of what’s going on in your life that’s causing you to write the story you’re telling. A lot of the stories I feel that I’ve created are actually just me processing something in my life. Those are the books I actually like the most, where they’re stories that just really … They don’t answer a lot of questions, they just ask a lot of questions, and they kind of leave you with that longing after you put the book down.

Frank Miller: Well said, well said.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah.

Frank Miller: Yeah.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Spiderwick came from a love of Dungeons and Dragons, a love of Brian Froud and Alan Lee, and Brian went on to work with Jim Henson for Labyrinth and The Dark Crystal. Alan Lee went on to work for that little film trilogy, Lord of the Rings. They were visionaries in their own right and had a huge impact on me. Growing up in Florida, I caught a lot of insects, because that’s what Florida’s full of.

Frank Miller: You monster.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Old people and bugs. Yeah. Bugs, big bugs.

Frank Miller: Living, sweet creatures, that do no harm. In fact, protect the environment.

Tony DiTerlizzi: When a mosquito with a nose that long …

Frank Miller: The last of its kind.

Tony DiTerlizzi: It would look great in a shadowbox. I agree with you, I love the weird in nature, and so I thought it would be interesting to make a field guide to-

Frank Miller: Kind of like Vincent Price loved all those women in all those movies.

Tony DiTerlizzi: I’m like that?

Frank Miller: Well, you love the insects, that’s why you kill them.

Tony DiTerlizzi: To make a field guide to women? Is that what you’re … Like Vincent Price? I will fail miserably at that. I had come up with this idea really out of boredom, Boris. I mean I was like 12 years old. I was home from summer break and I had left over school supplies. I thought about the monsters in Dungeons and Dragons. I thought about the folklore that I’d read in these fairies’ books, and I thought about field guides. I mean you can see the raw manna. I just took my Trapper Keeper, and each day I drew a monster, or a dragon, or a troll, and then I’d write this scientific mumbo jumbo jargon about it. Because I’d watch Roadrunner cartoons, I therefore knew Latin. I knew the Latin word for-

Boris: What are you laughing about?

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah. I knew the Latin word for dragon is like fireus breathus badus. Yeah, yeah, that’s it, yeah. I did this whole thing, and then I forgot about it. Then many years later I thought, “This would be a really cool concept for a book for 10 year old me. What could old Tony make that young Tony would want to read?” I worked with Holly Black on Spiderwick, and the interesting thing is I was older, but my family was going through a separation, which is a big part of Spiderwick.

That, to me, those are the best fantasy stories or science fiction stories, they’re not really about the monsters or the fairies, they’re actually about the real world problems that the character is coping with. The fantastic creatures or monsters, they’re manifestations of the fear and the anger, or whatever emotions are that are going on inside of them. There was definitely real world stuff that always affects how I make my books.

Frank Miller: Mm-hmm (affirmative), yeah, there always has to be. It has to have some sort of resonance, something that makes you actually feel something.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah.

Frank Miller: Because that’s where all mythology comes from anyway. I know you can be convinced otherwise in events like this, but there really aren’t dragons out there. They represent something in our minds.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah, I was thinking a lot of times my stories are about ordinary kids, like ordinary characters in extraordinary circumstances. Do you look at super … When I think of superheroes, I always think they’re extraordinary characters in extraordinary circumstances.

PART 2 OF 4 ENDS [00:28:04]

Tony DiTerlizzi: …I always think they’re extraordinary characters in extraordinary circumstances, but do you see it differently? Because you’ve got to find that shredded humanity that we can cling to so that we feel for them. Sorry, Borys, I’m taking over now. I’m going to start asking questions.

Frank Miller: I see these characters, excuse me, as normal people writ large. That is Batman at his heart is a… Somebody who started out as a scared little kid. When he’s five years old, all of a sudden his maniac came out of shadows with a gun and all the sense went out of his life. And so this little boy just had a choice sitting there with those corpses in front of him. He could just become a useless human being, become some lunatic walking the streets, or be someone who just took the money he inherited it and squandered it, destroying himself or whatever. Or he could take all that unbelievable rage and horror he had, and turn it against the forces that killed his parents. And so, he turned himself into a demon, but to hunt down the monsters. Obviously, the [inaudible 00:29:26] now in the comic books, in the original comic books, he actually got the guy who killed his parents.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Oh really?

Frank Miller: Yeah. Joe Chill.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That was the guy’s name?

Frank Miller: Yeah, it was bad. It was bad.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That sounds like an eighties character… “I’m Joe Chill.”

Frank Miller: No, it was…

Tony DiTerlizzi: “Hey ladies.”

Frank Miller: It was… No, it was a, I think, late forties, early fifties’ character. Early fifties. That was when they did the worst stuff. But it’s… The only way I could make it work was that he must never be satisfied.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Right.

Frank Miller: Must never have any of that thing we so conveniently call closure, and that it has to be an open wound for the rest of his life, so that he… That while he progresses on to become the greatest crime fighter the world will ever know, and a genius he’s still, at heart, a five-year-old boy with his eyes wide, staring into existential horror.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That’s awesome. That’s fascinating. It’s interesting… As you’re saying this, I’m thinking of Jared Grayson, the Spiderwick Chronicles. So, Jared is so angry about the divorce and the separation that his family is going through. And Mulgarath, the big bad, the big ogre, is also angry at what the humans have done to the fairy world. So, it has this parallel track that runs. And then at a certain point he sees it. So, I think this is the closure you’re probably talking about. And then decides to turn in a different direction. And Mulgarath doesn’t, and ultimately he pays the price for it. And so what you’re saying is with a superhero like Batman, that never happens. It never… There is no resolution for [crosstalk 00:31:10].

Frank Miller: No, there can’t ever because… Well, because really, if you think about it, Batman has every reason to just say, “I’m getting pretty tired. I got all the money in the world, and I can travel anywhere. And women just adore me because I’m just a handsome devil.”

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah.

Frank Miller: I mean, he’s not staying Batman because he’s got a great car. He’s got to have his motivation.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Do you think that’s why sequels sometimes, whether they’re in books or in film, don’t always work because the first thing is so self-contained? It does have closure and then they try to go reopen the wounds, so to speak. And it’s not as genuine.

Frank Miller: Yeah. I think the best kind of sequel is where you can actually move your focus. Either put the character through a completely different set of paces, or simply move from one character to another. That’s why I’m so happy with Sin City as a vehicle, is that… I mean, I established the ground rules in Sin City in the very first one because I said, “I’m going to introduce the lead character. People going to think Sin City is Marv’s comic and he’s going to die.”

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah.

Frank Miller: I set out from the beginning to lead to his death. And every page in Sin City is leading toward his death. He thinks about it all the time.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah.

Frank Miller: But once he died, then I figured I’d established that this was a very dangerous place, and I’d have all the freedom in the world.

Tony DiTerlizzi: So, the real main character is the city itself.

Frank Miller: Absolutely. Absolutely.

Boris: How do you guys tackle bad guys? We’ve been talking about heroes here now. Now what makes it [crosstalk 00:32:57]?

Tony DiTerlizzi: With relish.

Frank Miller: Yeah.

Tony DiTerlizzi: They’re only as good as their antagonist as the bad guy. I mean, again…

Frank Miller: They’re often a lot more fun to write.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah. Again, I think of like with, again with Spiderwick, when Holly and I were working on it we thought of Jared and Mulgarath are kind of the same. He’s like the bigger mutation of Jared. And then I’ve definitely… I always feel like they’re the best bad guys. You agree with their motivation at some point. You see…

Boris: Absolutely.

Frank Miller: Absolutely, yeah.

Tony DiTerlizzi: “I can see the logic in that. Wait a minute, what am I saying?” You know? Those are the best.

Frank Miller: Tony, I agree with that in almost every case. Sometimes, I think a character can reach the level of being satanic. And when I got to the Joker, I just decided to more… I looked at some of the oldest versions of the Joker, back in the Jerry Robinson days, and so on. And I just decided to go for broke, and make him so diabolical that there was no…

Tony DiTerlizzi: There was no glimmer of humanity left.

Frank Miller: There was nothing to relate to. He was not.. And I even made him sexually twisted so that you’d be afraid for little Robin when he was around. And there was the hints that what had happened to Jason Todd, and so on. And in that case, I wanted him to be a devil.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah.

Frank Miller: Whereas other villains, I think, can be wonderfully multi-dimensional characters.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That’s interesting. I definitely feel like with the books that I’ve written for children I… Again, I take these manifestations of the fears that I had when I was 10. You know?

Frank Miller: Sure.

Tony DiTerlizzi: What would happen if I lost my parents? How would I survive? And I think it’s also at that point in your life when you start to realize, at least for me, there’s your home that you’re cognitive and aware of when you’re very young. And then as you get older, there’s your neighborhood, your street. And it’s really, for me I felt, at least for me, as you’re leaving elementary school and going into middle school, that’s when you start to really become aware of the world, the larger world. That’s when you start to see the news and the stuff that’s going on in a bigger…. Your parents can’t shield you from it. And that’s when the real fears start to creep in.

Frank Miller: That’s an interesting observation, Tony, because I remember being horribly afraid when I was first grade. I grew up in a farmland Vermont and some of those bullies beat the snot out of me.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That’s true.

Frank Miller: [Crosstalk 00:35:39].

Tony DiTerlizzi: No, that’s…

Frank Miller: I believe childhood can be full of terror.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Oh, I agree with you a hundred percent. I’m referring… And you see it… And to this day, you still see it. I was thinking of the larger looming… I guess the reality of adulthood almost [crosstalk 00:35:57].

Boris: Oh, okay. The awareness.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah.

Boris: There’s like… Because school is very… Even high school is… You’re just focused on the day. If you don’t see university and life after university in high school, because it’s like you’re in ninth grade and you’re getting picked on, and that’s your life, and that’s… And you think that’s how it’s going to be forever.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That’s true.

Frank Miller: I would have killed myself if I thought that was the way it was going to be forever.

Tony DiTerlizzi: But I think those antagonists in real life… I mean, who am I to say? But I mean, if you had not been attacked, would you have created Dark Knight? Would you have done it?

Frank Miller: No. I can’t imagine, no. I mean, it’s too… I don’t know what kind of person any of us would’ve been if we’d grown up in a perfectly benign world. I mean, I just don’t think we really have much use for comic books.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah.

Frank Miller: I mean, it’s… Or for heroic stories anyway.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah.

Frank Miller: It does take a certain amount of adversity to… For there to be any reason for any kind of heroism.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah. Yeah.

Boris: Just switching tact here, you both have had your works translated into movies. How has that experience been for you both? And how is it like seeing your heroes change on screen?

Tony DiTerlizzi: I mean, I… You’re going to have a long… You’re going to have a much longer answer than me. I think that the… What a book has to accomplish for its readers to entertain those readers is different than what a film has to accomplish and deliver for its viewers. For me, if the core philosophy, the core theme, can be maintained and the integrity of the hero and what that hero has to do… The paces, as you said, they have to go through to get through this change, this cathartic change in their life. If that can be maintained, then I feel like we’re off to a good start. And fortunately for Spiderwick that they, the filmmakers, held on to that. So, I was very, very happy at that very philosophical, simple level. That’s because we’ve… I think we’ve all read a book, and you see the movie or the TV show and you’re like, “What did they do? What happened that…? He wouldn’t do that. She would never say that.” That’s when I think they, the filmmakers, have pivoted too far from the essence of who the character really is.

Frank Miller: Yeah.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That’s really… That’s what would be my answer with the… As far as heroes and protagonists are concerned. What about for you though?

Frank Miller: Well, my experience was magical in that I… It’s just kind of funny actually, because I had done some work in Hollywood, and I’d had my part in making a very bad movie. And I sat down to start Sin City after that and I said, “Well, I’m just going to do a comic book that can’t be adapted, that nobody can possibly make a movie out of this thing.” And so I sat down, I started Sin City and I said, “But the thing is, what I got in mind is so personal nobody’s going to want to read it. So, I’ll just bury it in this little anthology, Dark Horse Presents. And well, it… Obviously people liked it, so it got its own title and it kept going.

But then this crazy Texan calls me up and he goes, “Hey, Frank is Robert Rodriguez. I want to make a movie out of Sin City.” And I said, “No.” And he went, “What?” I said, “No, I really… I worked on a movie once. It didn’t work out real well and I… See, this is my baby and I don’t want it to turn into anything else because I don’t want people to just think of it as being a bad movie.” And he said, “Uh, okay.” Then my editor, Bob Schreck calls me up a couple of days later. No, it was the next day. And he said, “Frank, you’re an idiot.” He said, “Do you know who you’re talking to?” And I said, “No, no.” And he said, “You’ve got to take this meeting.” So, I took the meeting, I met that guy, and he’s really cool guy. And I said, “No.”

Tony DiTerlizzi: You said no?

Frank Miller: And he said, “Okay.” Then he called me the next day and said, “Look, I got an idea. I’ll fly you to Texas and we’ll do a test. Just a little test, take one of your short little stories. And it’d be like a two minute thing. If you don’t like it, we’ll just have a fun little movie we show to friends.” And I said, “How do you turn that down?” So, I took the flight to Texas, and he had his whole crew set up, and he had two actors, Josh Hartnett and Marley Shelton, ready to play in my little story The Customer Is Always Right. Which wound up being the first two minutes of the movie. And we shot it. And at the end of it, I just walked over and shook his hand and said, “You’re right. When do we start?” And the whole adventure began. Rodriguez is an amazing man.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That’s awesome.

Frank Miller: Yeah.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That was very, very cool.

Frank Miller: Yeah.

Boris: There’s a… Has there ever been an.. Because we’re obviously at Comic Con, has there been a fan interaction that has made you aware, grasp the kind of power or influence you guys have had on your readers?

Tony DiTerlizzi: I think when a kid, or an adult, comes up and says, “I want to draw… I became an artist, or I want to be an artist because I saw your work.” That validates… I mean, I told this to…

PART 3 OF 4 ENDS [00:42:04]

Tony DiTerlizzi: I mean, I told this to one of my heroes, Brian Froud, many years ago, and Brian said, we’re all linked. We’re all links in a chain that is all interconnected. And so, the idea of being linked to someone like Brian, who’s linked to Arthur Rackham, and being linked to someone like Frank, and then us creating, inspiring other people. It’s strange because I still perpetually see myself as a 10 year old, but it’s incredibly validating why I do what I do.

Frank Miller: Yeah. Well, I mean, I find so many of the interactions rewarding that way. I guess one thing that I find most personally gratifying is when I see some kid come up and he’s got stack of drawings he’s done that he’s worked very hard on and very seriously on, and I get to sit down with him and do what my mentors did with me.

Speaker 1: Chew them up and spit them out?

Frank Miller: No, I’m not much in New Yorker, okay? If it was someone who was just about ready to break in, then I’d chew them up, but if it’s someone who’s just getting started, I just point out things tho help them. But it’s very gratifying to see that the craft is living on and that it remains in very enthusiastic hands. Look, you’ve got to understand the history here. When I first showed up in New York, the first editor I saw at DC Comics was this sweet old guy who’d been in comics since the DC Comics. And he looked at me and he looked over my artwork and he just said, “Boy, you put a lot of work into this but, you know, everybody knows we’re going to be out of business in a couple of years. There won’t be any more comic books. So why don’t you just go back to, where is it? Vermont? Go back to Vermont, get a job, sell books, but there won’t be any comic books”. And I think back on that and I sit here and it’s wrong.

Boris: Well another thing too, speaking of fans, I mean, there’s an entire industry because of your Daredevil work, which is Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

Frank Miller: Oh yeah, yeah.

Boris: Which was created as an homage to you. So when that first came out, how did you feel seeing-

Tony DiTerlizzi: It was Ronan, right? Actually it was almost like a parody of Ronan?

Frank Miller: Yeah. Give these guys credit. Sure, they used some of Daredevil, some of Ronan. They were big fans of my stuff, obviously. Give these guys credit. They came up with about the best name for a comic book anybody ever heard of. It was every cliche, trendy thing in comics at the time packed into one thing with turtles tacked on the end. Because they couldn’t draw people. It was brilliant. I mean, it wasn’t my stuff that got spun off into 18 movies and cartoon shows and a toy line that goes on around the park. Bless them. They did great.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah they did.

Boris: Any questions from the crowd? Quickly while we still have time. Anyone?

Tony DiTerlizzi: Anyone? Bueller? Bueller?

Boris: You, sir.

Speaker 2: I got to, gosh, a decade ago, Tony. Your wife took credit for your being found. I was always wondering if I could get your take on how you broke into the industry?

Frank Miller: Oh, it talks about being found. His mother lost him in a shopping center.

Tony DiTerlizzi: My wife did break me into … It’s true. I’m very fortunate in that I have an incredible partner and my best friend in Angela, and yes, she’s here. I know she’s here. I also have to get on a plane and fly home to her so, I mean, you know. No, it is, and I’m sure you could probably comment on this too, Frank. When you’re living in New York, it’s the publishing center of America and all the children’s publishers are there, and it was in the nineties. It was very hard to break in and talent alone was not going to do it for me. And Angela was a makeup artist in Soho, and this woman came in and she had a Scholastic book bag. And she came in to get makeup done and Angela was like, all right. She did one eye and the woman’s like, oh my God, it looks beautiful. “I’ll do the other eye, but I need your business card”. And the woman was like, “Okay”.

So she gave her the card and I went in and there was a bunch of editors. At the time, in the nineties, if you can believe this, they were like, “Your stuff’s all fantasy and dragons and monsters. We’re not into that”. This of course would be Scholastic who would go on to publish Harry Potter-

Frank Miller: What did they put? Only do stories about selling drugs? What?

Tony DiTerlizzi: Non-fiction, that’s what we want. So I ended up meeting this one editor and he left Scholastic and went to Simon & Schuster, and I’ve published with them ever since. So I’m very, very lucky.

Frank Miller: That’s great.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah.

Frank Miller: That longstanding relationship wonderful.

Tony DiTerlizzi: It’s good. You should try that sometime. You might … No, not having a longstanding relationship. You should try Simon & Schuster. I’m giving you a segue of-

Frank Miller: Oh, I see. Okay.

Tony DiTerlizzi: You should try working with Simon & Schuster. That might be something interesting.

Frank Miller: Mm-hmm (affirmative). What do I say? He talks to me about a publisher. That’s shop talk, man. Come on.

Tony DiTerlizzi: I’m just saying, it’d be kind of, I mean, you’ve done a lot of cool comics. I mean, I think it’d be cool if you did a kid’s book.

Frank Miller: Oh, I’d love to.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Wouldn’t it be kind of cool?

Frank Miller: I’d love to do a kids book, yeah. I’ve wanted to for a long time.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Yeah, it’d be cool.

Boris: What about you, Tony? Any comics in your future?

Tony DiTerlizzi: Well, let’s go back to my Will Eisner class where I show-

Frank Miller: Boy, he ducks and dodges. Watch Tony hide under a flat rock.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Will Eisner was like, “Yeah, you’re a really good illustrator. You’ll never be a comic book artist”. That’s what he told me.

Frank Miller: God, he had a way of just charging you up and telling you, take the land.

Tony DiTerlizzi: Feeling good. I then start at joining the comic book artists, grabbing his drawings of spirits so I could sell them on eBay later and try to make some money.

Boris: One last question.

Tony DiTerlizzi: That’s all I got on that.

Boris: Over there.

Speaker 3: Frank, when you transitioned from artist to writer with Daredevil, your [inaudible 00:49:37] was really well written. Did you need to outline first, and how involved was editorial with your writing process?

Frank Miller: When I wrote Daredevil?

Speaker 3: Yeah.

Frank Miller: Well, I would outline the stories very carefully, and at the time, the method of working was that I would submit a plot that was a couple of typed pages to the editor. And, I’m sorry, what was the second part of your question?

Speaker 3: How involved was editorial with your writing process?

Frank Miller: Far too much. But you’ll hear that from any of us. But no, there was a lot of give and take. There has to be when you’re working with characters that are owned by the publisher, especially with the superheroes, because they’re all tied into so many other things. And if you all of a sudden want to put Spider Man in your story, the Spider Man people get their panties in a bunch, so everything’s got to be negotiated.

Boris: I think that’s it. That’s all the time we have.

VIDEO

IMAGE GALLERY

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration explores fantasy archetypes from the Middle Ages to today. The exhibition will present the immutable concepts of mythology, fairy tales, fables, good versus evil, and heroes and villains through paintings, etchings, drawings, and digital art created by artists from long ago to illustrators working today.

The exhibition Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration is organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA, and will be on view here from June 12 through October 31, 2021.