Episode 13: Patrick Wilshire

Jesse Kowalski: Welcome to The Illustrator’s Studio. I am Jesse Kowalski, Curator of Exhibitions at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. The Illustrator’s Studio is a weekly interview series, a project of the Museum’s Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies. In this episode of The Illustrator’s Studio, we welcome Patrick Wilshire. Wilshire is the first guest on this program who is not an artist, though his work behind the scenes has helped boost the visibility and perception of fantasy and science fiction illustration. Through his annual IX Arts conference, Wilshire and his wife Jeannie gather many of the top illustrators in the country, as well as emerging artists, to exhibit their work, give lectures, lead art demonstrations and webinars, and meet with fellow artists. Welcome, Patrick.

Patrick Wilshire: Hi, welcome. Thank you. It’s good to be here.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah. So, I am planning a fantasy exhibit at the Rockwell Museum this summer called “Enchanted.” And, many of the artists who appear at the IX Arts conference are in the show. And, when I started planning the exhibits, there were a few key fantasy artists I reached out to, to kind of bounce questions off of and get their opinions on certain things, fantasy versus science fiction and things like that. But, you were also one of the people I contacted in the beginning, because you are an expert in the field. So, how did your career get started?

Patrick Wilshire: Well, basically, it started from the collecting perspective. I had been a fan of imaginative artwork ever since I was a kid, so I started playing D & D when I was 10. And so, I was flushed with the fabulous early TSR illustration. And then, I became a reader of fantasy and science fiction shortly thereafter, and was exposed to all of that. And, when I was in my mid-twenties, I started collecting original science fiction and fantasy imaginative work. And, as I collected over the span of years and got to know more and more collectors and more and more artists, my involvement in the field kind of expanded from just being a collector to kind of coordinating collectors, to coordinating artists and collectors, to eventually where we are now, where sometimes I swear we coordinate everything.

Jesse Kowalski: In 2012, you curated an exhibition at the Allentown Art Museum titled, “At the Edge Art of the Fantastic,” which was a very influential exhibit. So, how did that originate?

Patrick Wilshire: Well actually, that originated, an artist who was an IX exhibitor, named Jeremy Caniglia, back in the early, or about the late aughts , I guess, happened be friends with the then director of the Allentown Art Museum, Brooks Joiner. And, Jeremy had mentioned to Brooks that, hey, this is, you should be doing a show of this kind of subject matter, and Brooks was sort of intrigued. And so, he talked to us and he came to one of the early IXs in Altoona, and then said that they would like to have us curate a large exhibition for them of imaginative realist work. And so, we kind of assembled that and over the course of the project, our scope expanded and their budget contracted. So we got to deal with that. There were a lot of things that we had talked with other institutions and had agreed on some institutional loans that then ended up getting cut for lack of budget. So, it wasn’t quite as comprehensive in the end result as we had originally hoped, but we still ended up showing, I think, roughly 140 artists exhibiting in that show. And, it really kind of covered the gamut. We did not have much 19th century representation because those are the things that got cut when the budget got cut, but it was a pretty solid representation of turn of the century to the present. A lot of collectors were fabulously willing to lend work to the show. Of course, all the artists were willing to lend work to the show. And, that was a really interesting experience, and the show at the time, at least, when it happened, was the best attended show that the Allentown Museum had ever had.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah, so when you were planning the exhibit, which is science fiction and fantasy, or was it one or the other, or where was the cutoff?

Patrick Wilshire: It was imaginative work. It covered both.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah, okay. You often use the phrase “imaginative realism” over “fantasy.” Could you define what that is and why you prefer that phrase?

Patrick Wilshire: Oh, sure. Well, imaginative realism is, we didn’t actually invent the term. It appeared sporadically for quite some time back, but no one was actually using it. And, we thought that this genre really needed a proper term that encompassed the field, but actually put it in some kind of an art historical context. Fantasy and science fiction art doesn’t tell you anything about where it fits on the kind of the art continuum and not everything is technically fantasy and science fiction art. Or, fantasy and science fiction illustration. Imaginative realism is a little broader than that. And so, we decided on imaginative realism because, okay, it’s specific, it’s fairly clear. If you just hear the word imaginative realism, what is it, it’s the realistic depiction of the unreal. Okay. That makes sense. It’s logical. It slots in as a genre of realist art. And so, we think that just kind of gives it a better understanding for people, especially since now, a huge quantity of work that’s being done in this field today has nothing to do with illustration at all.

Jesse Kowalski: No, no, I completely agree. And, one of the early criticisms of doing a show on fantasy illustration at the museum was kind of this stigma that it’s art for teenagers, pimply teenagers, or it’s babes in bikinis, that kind of thing. How have you seen the stigma change over the years?

Patrick Wilshire: Well, I think the stigma has changed dramatically over the last fifteen years. Even that short a time span has been a dramatic change. And, I really think a lot of it simply boils down to, I just turned fifty, I was six years old when Star Wars came out. So, I consider myself part of the Star Wars generation. And, I think really part of what you’re seeing is simply that the taste makers, the museum curators and the gallerists, and you’re now getting people running galleries and running museums who are in their forties and fifties, who grew up with imaginative subject matter as a straightforward, popular, well-known and respected genre in literature, in film, in everywhere else, and so, yeah, a dragon is not really any different than a horse, it’s just cooler.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah, and I think when you put things in context with artists, like Gustave Doré, or John Martin, or Turner, I think that helps further the field quite a bit.

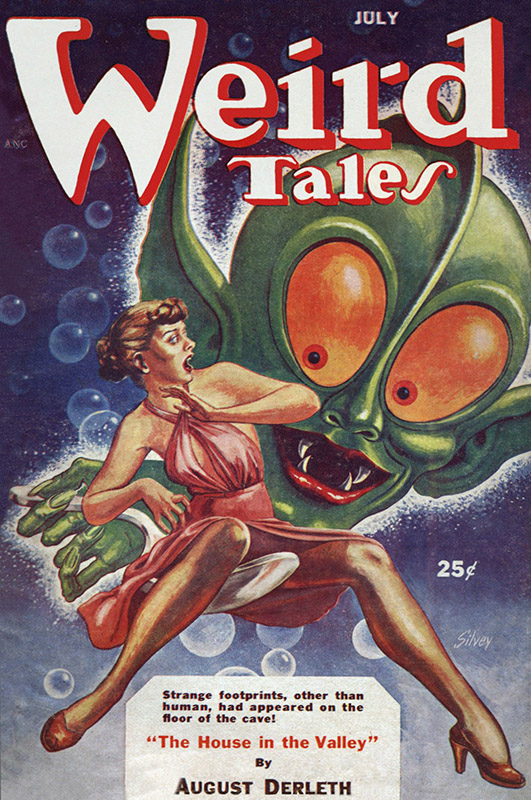

Patrick Wilshire: It makes a big difference when you show that long track and also, people have a tendency when they think science fiction art, or they think fantasy arts, they just think of just those terms, they’re having some mixture of bad bug-eyed monster art from the fifties, or the side of someone’s van that’s been painted in the seventies or those Spencer’s Gifts black light posters. And, the recognition that actually in the long-term history, those kinds of things are the outliers and not the typical, and I can go on at endless length about the span and how the work that was happening largely in the thirties, through the sixties, kind of deviates out from the actual longer term history of the field. But, people, they just have that sort of impression and they haven’t really paid attention otherwise. They’re not looking, they’re not out at the bookstore perusing, and you can’t really tell that much from book covers anyway. Nobody would ever expect that you’re going to judge the art historical quality of the Mona Lisa by looking at a forty year old postcard. But effectively, that’s what you do with anything that’s illustration-based because prior to museum shows like these, or shows like IX, there was no way to see them. Either you bought them, or you never saw the originals.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah, no. When I started planning the exhibit, I expected there would be some reticence, I guess, from other museums to loan because of the content and, sure enough, there was some, but I was happily surprised to find two museums that are going to take the exhibition after the Rockwell Museum. There’s the Hunter Museum in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and then the Flint Institute in Flint, Michigan. And, it’s funny that I’ve worked with both museums before in my career, back when I worked at The Andy Warhol Museum. So, it seems like they kind of know what the public wants and they know what will bring the visitors in.

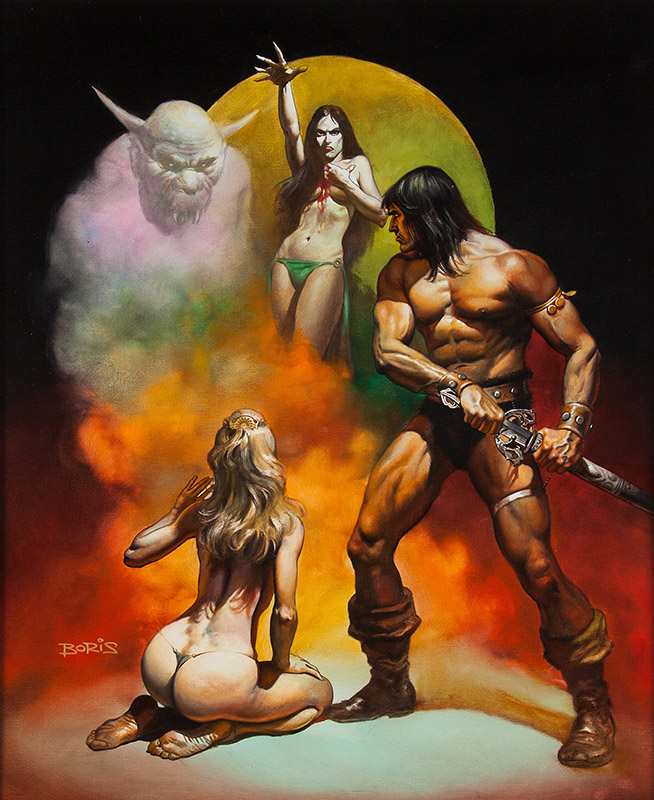

Patrick Wilshire: It will absolutely bring the visitors in. And, I think shows like this are incredibly important because it is so important to be able to show people, if you want them to treat art seriously, you need to show it to them in a serious context. So, I can guarantee you, if you take a Frank Frazetta Conan painting to pick what is now a multi-million dollar piece of art, as an example, and you put it up on a peg board at a show and say, “The cover to Conan the Adventurer…,” versus, you take the same painting and you put it in a museum and you put it on a museum wall and you show it as, “Conan the Adventurer, Frank Frazetta, blah, blah, blah.” People respond to the work differently because they will give it much more serious consideration in one context than they will in the other. The work doesn’t change. It’s just the framework that people put it in.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah, I’ve found that to be the case with Rockwell, everyone’s seen his paintings a million times, on the Saturday Evening Post or in the news or calendars or whatever. But, when people come to the museum, they’re really blown away by the physical artwork, and every now and then you get a visitor who asks, “Where do you, where do you keep the real artwork?,” because they’re convinced it’s not the real painting on the wall because it’s so amazing. So that’s fun to see.

Patrick Wilshire: There’s always been, because I heard this, decades ago, there was always among people who did consider it, which was not a lot of people, but there was always kind of this sort of perception that illustrators, because they were working on deadlines, they were working on commission, they were working for reproduction and paperback size, that they cut corners and they were sloppy. And, it’s like, well, yeah, it looks fine at six inches by nine inches, but they’re just doing it quick to get it out and meet the deadline. And, until you see the originals, you can’t tell that that’s not true. But then, when you see the original, 36 by 48 painting, and it’s magnificent top to bottom, corner to corner, it’s like, oh, well they weren’t, they were making a fabulous work of art. It just got reproduced to this big.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah, and so, when did the IX conference start and how did it get started? And I guess, how have you seen it grow over the years?

Patrick Wilshire: Well, the IX show started… 2008 was the first IX show. And, it started, it’s a great story. We did the very first thing we ever did, exhibitionally speaking, was we live in Altoona, Pennsylvania, and Penn State Altoona is here. And so, we did an exhibition of about 25 pieces from our collection at the art gallery at Penn State Altoona. And when we did that, we invited all of the artists whose work we were showing to come to the opening. And, we were showing a Boris Vallejo paining from our collection in the show. And so, we invited Boris and Julie to come to the opening because they live in Pennsylvania. And, they were not able to make it to the opening. They had a prior commitment, but they invited us as a result to come out to the studio and visit. So, we drove out to the studio and went to visit and conversation was going on, I was talking with Boris and with Dave Palumbo, one of Julie’s sons, who’s also an artist, who was there and Jeannie was talking with Julie and in the Jeannie-Julie conversation, the topic of shows came up and Julie talking about how, well they didn’t do shows anymore. You know, they didn’t do Comicons or things because it was just sit there and sign autographs, like a caged animal on display. And, there was no good appreciation of the art or the artwork and Jeannie said, “Oh, well, isn’t there a show for the art, for the artists?” And, Julie said, “No, there isn’t, there is no show that’s just about the art and the artists.” And, “You should make one, if you did, we’d come.” So, after this meeting, we were actually leaving Boris and Julie’s and going to the Frazetta Museum to visit for the weekend. So, on the way, Jeannie and I talked about it and it’s like, well, we could do a show. There should be a show. People should get the chance to see the work and how hard could it be? Which, if we’d asked that question a little more thoughtfully, we probably wouldn’t have done it. But, in the end, we decided, okay, well, we could probably do this. And so, when we got back, we reached out to a lot of the artists that we knew and said, “Hey, if we did this thing here, would you come?” Because we knew if the artists came, the collectors would come. And so, the artists said, yeah, that sounds really cool, we’d come. And so, we held the first show and there were, I think, 42 artists exhibiting in the first show. And, we had, I think about 150 people total at that event, but it was successful, the artists sold $100,000 worth of art in the event and they were happy and the collectors were happy and everybody had a great time. And so, we said, “Okay, well, hey, we’ll do it again.” And then, over the years, it’s expanded and expanded and added new pieces and new parts. And now, it’s 220 artists or so, and we’ve changed venues a couple of times to get bigger, but that’s where we are. So, now we’re now looking at 2021 and which hopefully, we will actually be able to have, as normal, in October. The 2020 show was online-only, thanks to COVID, but we’re thinking positively that we can at least have a vaccinated-only show, come this October and kind of get things back in gear again.

Jesse Kowalski: Before you started working on IX, what was your day job?

Patrick Wilshire: My day job up until late 2016, actually, so through the first ten IXs or whatever, my day job was I was an instructional designer. I worked as an instructional designer. I worked for a government contracting company out of DC. I developed, I worked principally for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, developing training for long-term care surveyors. Previously, I did a lot of work with the EPA and other stuff, but that’s what I did. And, that continued up until fall of 2016, and at that point, we, Jeannie and I both started doing IX full-time.

Jesse Kowalski: Okay, I’m going to name some artists here. So if you could tell me your thoughts on their art and why they stand out, what makes them so special. Let’s start with a big one – Frank Frazetta.

Patrick Wilshire: Frank Frazetta. Frank Frazetta, we kind of identify Frazetta as being the point where the tradition of imaginative arts sort of ends its branching and sort of rejoins in modern imaginative art. Where the Brandywine tradition and the pre-Brandywine artists, the 19th century artists, that whole set kind of fades over the thirties, forties, fifties, sixties. And then, Frazetta is the one that kind of brings that tradition back. And then, everyone who has followed Frazetta has done that. So, that’s kind of what we consider his, he is the first modern imaginative artist to really go beyond illustration.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah, and still, his name is now a brand and his granddaughter, Sara, runs Frazetta Girls and they’re going gangbusters. So, what is it about Frazetta’s work that strikes a chord with people?

Patrick Wilshire: Frazetta’s work, it strikes a chord because it’s powerful. For lack of any better word of describing Frank’s work, it’s powerful. It has an immediate visceral impact. And, it’s obviously, they’re wonderfully well-painted. Particularly, if you get the chance to see the originals. The reproduction does not do the originals a great favor over the years. Now, there are, subsequently, there have been very nice reproductions in Frazetta art books and stuff, but as far as the original publications, not doing the pieces any favors. And, but, I think it’s really just a visceral energy that those pieces have. Frank was the master of motion, and it’s interesting because if you look at his work, if you look at a lot of his paintings, and if you look at it carefully, and you look at it really critically, a lot of his anatomical are wrong, they’re not actually correct, but they’re wrong in exactly the right way to provide this dynamism in the work. And, we think a lot of that comes from Frank being led back to looking at the work of people like J. Allen St. John, who had been largely ignored except by Frazetta’s friend, Roy Krenkel, who was a great student of the work, and he introduced Frank to a lot of these artists. People like St. John, people like Lindsay, people like Norman Lindsay, someone who’s not even really an illustrator in the genre per se. But, if you look at Norman Lindsay’s nudes and you look at Frank’s watercolor nudes, there’s clearly a significant, and I think that’s a lot of what, where Frank was really able to kind of appear on the scene with this, oh my God explosion. Because the artists for decades prior to that had not been paying any attention to the previous, the older works, the older traditions. They were kind of going about their own things. And then, particularly you get into the fifties and into the sixties and artists, they’re pulling in, they’re pulling in influences from contemporary arts. You get a lot of post-modernist, a lot of pastiche covers and a lot of these little collagey sort of things and going on because, and then Frank is suddenly, it’s like, no, suddenly it’s 1912 when you look at Frank’s work, and people hadn’t seen that for awhile.

Jesse Kowalski: And, how about Brian Froud?

Patrick Wilshire: Brian Froud really kind of caught the attention, I think, of everybody with sort of whole new fairies. I mean, not that people weren’t painting fairies. But he, again, Froud is a direct dribble out of Arthur Rackham and Dulac, and a number of the Golden Age illustrators where no one had been doing much like that for an extended period of time, and all of a sudden, there’s Brian Froud with these amazing watercolors. And, Brian also was able to increase his influence because at the same time, he also was doing film concept work for things like Labyrinth, which also had a really significant cultural effect or cultural impact. And so, he again, had exactly the right stuff and exactly the right time and was going back to an older tradition.

Jesse Kowalski: And, you mentioned Boris Vallejo and of course, we can’t forget his wife, who’s equally talented, Julie Bell.

Patrick Wilshire: Yes. Boris and Julie are really an interesting study. Boris, of course, is kind of one of the grand masters. Boris, his career is really starting up in the early seventies, he’s post-Frazetta, but he’s taking a different approach than Frazetta. Obviously, Frazetta is much more painterly, Boris is much more highly rendered. But it becomes that kind of ubiquitous sort of thing because his work again has a lot of power to it and a lot of impact to it, albeit in a different way than Frank’s. And, Julie has really been kind of the, sort of the avatar of the illustration to imaginative realism. Julie started out as an illustrator. She illustrated, she did covers, her work was similar to Boris’s, but different, different palette, different, she very much liked shiny things, metals and much more than Boris. But then, Julie started doing gallery work and taking her imagery into another kind of place and has been extremely successful at doing that. And, lots of other artists are doing the same thing, but Julie is kind of, one of the ones that would come to mind is, who’s been the most successful at making that transition from illustrator to galleries in Manhattan.

Jesse Kowalski: No, and Julie’s such a sweetheart. I had been in touch with her while, before I attended the IX Arts show in 2019. And, I went up to her at the conference and I introduced myself in person and she gave me a hug and she said, so sweet and so welcoming and throughout the whole exhibit and the delay because of the pandemic and everything, she’s been really helpful in organizing her art, Boris’s art, also her children, Anthony and David, they’re also in the exhibit. So, she’s been super.

Patrick Wilshire: I do not think that a sweeter person than Julie Bell actually exists on the planet.

Jesse Kowalski: And Donato Giancola.

Patrick Wilshire: Donato is a force. He appeared in the mid-nineties and kind of made his bones with science fiction, with metals and hard materials, and just lots of shiny things is kind of what first, because he did that better than anybody else was doing that. And then, from there, of course he expanded, he has become more painterly than he was earlier in his career, although he’s still pretty rendered, but he’s more painterly than he was. And, now Donato paints everything and is known for everything. And, I guess at this point, if you want to say, “What’s a Donato,” it’s astronauts, kind of a big, a big theme, and Lord of the Rings is a main theme for Donato.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah. Yeah.

Patrick Wilshire: But again, Donato, is super heavily influenced by 19th century and earlier painters.

Jesse Kowalski: Yeah, I think generations from now, people are going to look back and Donato is going to be a Frazetta or Vallejo to a lot of artists.

Patrick Wilshire: Yeah, I think so. There will be an awful lot of, and he’s been that way. He’s always been very involved with students and with sharing information and sharing. That’s one of the really nice things about the imaginative artists, kind of as a group there’s, compared to at least what we have experienced, and what we have been told about, compared to some other areas, including just broad contemporary realism. The, a lot of those areas are much more cutthroat than imaginative art, as a genre, has been more supportive. The artists in it tend to be more supportive of each other and younger artists.

Jesse Kowalski: Well, that’s all the time we have for now, Patrick. Thank you so much for joining us today.

Patrick Wilshire: You’re very welcome, and thank you. It was a privilege and a pleasure to be here.

Jesse Kowalski: For more information, check out Patrick’s website at ix-online.com and you can check him out on Facebook under IX arts. Also, please visit our own websites. nrm.org, illustrationhistory.org, and visit the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies at rockwellcenter.org. And always, don’t forget to subscribe to be notified for the latest content. This has been a production of the Norman Rockwell Museum. To watch the video of this podcast, or to see the images referenced in this episode, please visit nrm.org/podcast. New episodes from The Illustrator’s Studio are released every Monday. For questions or comments, please email us at podcast@nrm.org.

VIDEO

IMAGE GALLERY

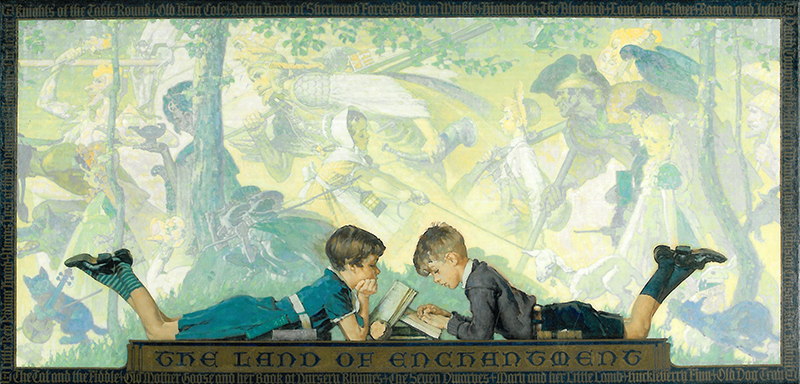

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration

Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration explores fantasy archetypes from the Middle Ages to today. The exhibition will present the immutable concepts of mythology, fairy tales, fables, good versus evil, and heroes and villains through paintings, etchings, drawings, and digital art created by artists from long ago to illustrators working today.

The exhibition Enchanted: A History of Fantasy Illustration is organized by the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA, and will be on view here from June 12 through October 31, 2021.