By Robert Young, grad student MICA’s MFA Illustration Practice, Fall 2013, Critical Seminar Final Paper.

In 1954, the psychiatrist Frederic Wertham published a book called Seduction of the Innocent. This book described comic books as a detrimental element in American culture that lead to delinquency and stunted the literacy of American youth. His book and its sensational theories caused a panic in the parents of America and this lead to a backlash against comic books and their publishers. This same year, the Comics Code Authority (the CCA) was established voluntarily by several of the larger publishers of comics to self-censor any sort of perceived unpleasantness in the form of gore, horror, violence, glorification of crime or drug use, and any other sort of element that American culture had identified as being youth harming at the time. This self-censorship drove out several popular comics publishers that specialized in horror and true crime stories, most notably EC comics. The creation of this code lead to a counter-culture revolution of independent, underground comics which not only did not abide by the stipulations installed by the CCA to govern what was acceptable in comics, but the underground comics purposefully acted in direct violation to what was deemed appropriate by the CCA. A quote from the author of Comic Books As History, Joseph Witek illustrates this: “The comix creators cultivated an outlaw image, and their works systematically flung down and danced upon every American standard of good taste, artistic competence, political coherence, and sexual restraint; in so doing they created works in the sequential art medium of unparalleled vigor, virtuosity, and spontaneity – after the underground comix, the Comics Code would never be the same”.

In this paper I will discuss why autobiographical sequential art has been and remains popular, as well as what functions they may serve in the realms of visual art and literature which are unique to sequential art, and why autobiographical comics are important in the realm of storytelling. Primarily, I will be looking at Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home, Craig Thompson’s Blankets, and Ken Dahl’s Monsters, but the ideas I present may be applied to all autobiographical comics.

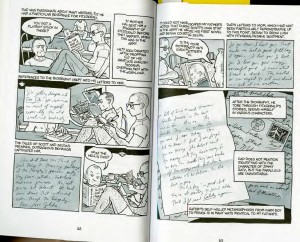

Autobiography in literature serves the purpose of connecting the reader to the personal history and circumstances that make up another individual human being, and in so doing gives the reader a greater understanding of humanity as a whole and allows them, hopefully, to become more sympathetic to the problem of the human condition. This is true also for autobiography in comics, but the tandem visual and literary dynamic of sequential art gives the author a greater ability to control the experience of the reader and guide them in the way that they wish through their story. Why, though, does this matter? Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home could easily have been presented as a literary memoir of Bechdel’s life growing up in a funeral home, her realization that she was gay during college, and the suicide of her closeted gay father. However, with the addition of Bechdel’s visual account of her personal history she is given the option to display human emotions visually to greater effect. A reader of prose would only be able to imagine the letters and family photographs that Bechdel painstakingly recreates in her drawings. These documents could be scanned and presented along with the prose, but they would then serve solely as documentation, while Bechdel’s drawings aren’t the documentation itself, but rather her own experiences with this documentation. It is a way of showing the subjectivity of the author which is an underlying theme of Fun Home as a whole. The visual subjectivity of Bechdel is echoed in the story when she reveals that it actually isn’t clear that her father committed suicide when he was hit by a truck on the side of a road while doing housework on a property that he was repairing. Storytelling, historically, was done in person by an older member of a community to impart wisdom and life lessons to younger members of the community. The storyteller was providing a visualized version of the story they were telling through their body language, placing emphasis through action on certain parts of the story and by guiding the listener through the tale visually as well as verbally. What autobiographical comics creators like Bechdel are doing is similar and an avenue that would be unavailable in a story told using prose alone.

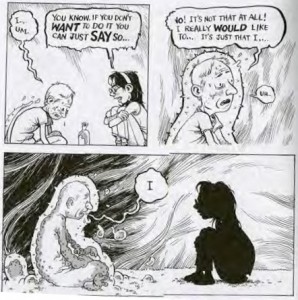

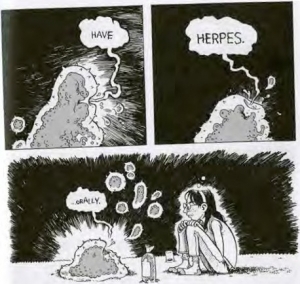

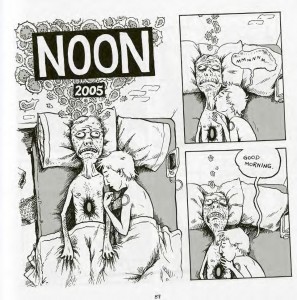

While Fun Home contains themes that, I believe, would appeal to a large audience even were it to be presented in prose alone, Ken Dahl’s Monsters does not have that same widespread appeal. Monsters describes a period of the author’s life after he tested positive for the herpes simplex virus and his subsequent transgressions committed while withholding that information from women that he was dating and/or slept with. When the underground comics creators of the sixties and seventies began bucking the system and the Comics Code Authority, they often did so autobiographically by telling mundane stories in a visceral way. They told stories that showed how gross the human body is and how many mistakes people make as they navigate through life. The appeal of this to many was that it elevated the mundane aspects of everyday life to a higher level of importance by pointing out that while these everyday screw-ups and scatological events seem like nothing when viewed on an individual level, the fact that they are a shared experience marks them as invaluable to understanding who and what we even are as a species. While no long form comic is made without substantial effort and investment of time, Ken Dahl’s Monsters is significantly shorter than something like Maus by Art Spiegelman or Blankets by Craig Thompson. It is this shortness that appeals to autobiographical comic creators in many instances and contributes to the relatively low barrier of entry to this form of personal storytelling. A story like Monsters doesn’t have the wide content appeal that some other autobiographical comics have, nor would it have the length in prose form to warrant a book, and so would be relegated to an article or as part of an anthology which it would then be sharing space with other author’s work. In comic form, such a story has more physical presence in that it is a five-inch square book, and more literary importance in being presented by itself and not surrounded by the work of others. There is also a greater element if intimacy in a story presented in a comics format. Since the content of Monsters deals with adult sexual relationships, a visual representation of this brings the reader in closer to the situation. It is a different sort of effect and connection with the reader that can be achieved through a graphic depiction of sex than with a purely literary account of a sexual act. These sorts of choices allow the creator far more control over the experience of the reader and how their story is presented and this is a major draw for storytellers. Self-caricature is another mechanism which exists in the medium of comics that exists only to a muted degree in traditional literary autobiography. Ken Dahl portrays himself in an unpleasant physical light in Monsters and often shows himself turning into or being bombarded by a squirming, translucent, that represents an idealized herpes virus. Charles Hatfiled is referring to Alison Bechdel when he says “The cartoonist projects and objectifies his or her inward sense of self, achieving at once a sense of intimacy and a critical distance. It is the graphic exploitation of this duality that distinguishes autobiography in comics from most autobiography in prose.” [2]

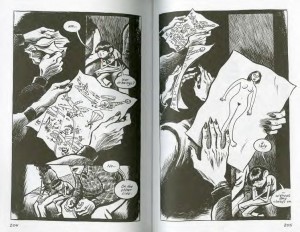

One of the most important aspects of autobiographical graphic novels that I don’t believe exists in traditional literary autobiography, is the ability for the author to enter the reader’s physical space through use of the visual mechanics inherent comics. For instance, the full bleed spread in Fun Home depicting a hand holding a Polaroid of a nude man makes it seem as though it is the reader’s hand holds the Polaroid. Craig Thompson also uses this effect in Blankets when his parents confront him about a drawing of his they found in which he had depicted a nude woman. He shows us the first person view of his parents’ which mimics the first person view the reader would have in real life while holding the physical booking and reading it. This is a sort of psychological effect that is used often in film and comics to get the reader to relate to a character or feel that they are part of the story rather than a passive observer and is also an effect that is not possible in literary form.

In conclusion, there are many reasons why autobiography has been and will remain a popular subject matter for comics creators. The author has greater control over the experience of the viewer. There is a lower barrier of entry to comics than there is to a literary book, which allows for more mundane personal stories to be distributed. The connection between the author and viewer is more intimate. There are visual mechanisms in comics that don’t exist in literature.

Works Cited

Witek, Joseph. Comic Books as History. (Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi, 1989)

Hatfield, Charles. Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2005)

Dahl, Ken. Monsters. (New York: Secret Acres, 2009)

Bechdel, Alison. Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. (New York: First Mariner Books, 2007)

Thompson, Craig. Blankets. (Georgia: Top Shelf Productions, 2003)