By Sarah Schneider, grad student MICA’s Illustration Practice, Fall 2013, Critical Seminar Final Paper.

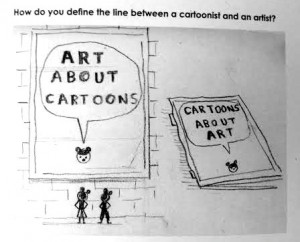

Comics have historically been separated from art and literature, cast off as a ‘low brow’ art form in the public consciousness. Generally created for reproduction, either as a disposable booklet or a humorous addition to newspapers and magazines, cartoonists were not regarded as artists, and their work was culturally disregarded. However, in the past fifty years, a lot has changed in the world of comics and sequential art. Many of the characteristics people considered to be defining aspects of the medium have fallen by the wayside, as younger artists experiment with the juxtaposition of words and images in ways previously unheard of. So much has been done in the realm of ‘comics’, the definition has become convoluted, and many of the distinctions that kept cartoonists from being considered artists are becoming obsolete. Currently, it is difficult to find a clear explanation of the difference between cartoonists and artists. Some of the only explanations still applicable have to do with context. Art is shown in a gallery, comics are reproduced in printed forms. Many artists utilize both contexts simultaneously and without biased, making it even harder to find people who fit under one label and not the other. (Gravett)

Although comics were previously thought of as a mainstream art form, aiming to appeal to large audiences through horror, romance, and humor, the medium lends itself well as an avenue for more difficult and engaging ideas. Small scale, accessible to large audiences, and intimate in nature, the potential for comics as a means to story telling, political, social and personal commentary has given countless artists an ideal means to uncensored self expression. (Gravett) Certain artists have utilized the combination of words and pictures, the essential element of comics, to create loose, poetic, personal narratives.

When artists Raymond Pettibon and Marcel Dzama began creating drawings on a small scale in a cartoonish or illustrative style, the sophisticated ideas and non-linear narratives that ran through out them distinguished them from what could be considered comics. In the late 1970 and 1990s when these artists began their careers, their work appealed more appropriately to those frequenting art galleries than the usual comic book crowd. Although they are considered fine artists, their works has been reproduced in countless magazines, books, and prints. Occupying both galleries and print forms, this innovative work helped broaden perspectives on the creative potential for illustrative and cartoonish artwork. The tension between the recognizable and accessible imagery and the obscure or difficult ideas they expressed captivated both fans of comics and fine art. Not exactly fine art, not quite comics, Pettibon and Dzama helped create a space for new kinds of work to be made, work that is both comics and art.

Raymond Pettibon (b. 1957)

No Title (And now the…) 1987

Ink on Paper

In the late 1970s, Raymond Pettibon quit his job as a high school math teacher in California to pursue art full time. Brother to Greg Ginn, the founder of punk band Black Flag, the artwork of Pettibon appeared on record covers and flyers of many bands in the punk scene at of the time. Pettibon has a consistent and recognizable comic-like style and is regarded one of the most significant artists of the past century. Combining single images, usually appropriated from various sources, with text he lifts from literature and popular culture, to create work that is often satirical or anti-authoritarian in nature. He uses one or two bold colors, loose draftsmanship, with hand written type to create his distinctive visual style. Although his work resembles cartoons in a direct way, Pettibon asserts his work is not cartoons or literature, but something else, a response to both. In an interview with Denis Cooper, Pettibon discusses the differences between comics and fine art, and many of his answers are confused or contradictory. He says he feels uncomfortable drawing a distinction between artists and cartoonists but doesn’t think it makes sense to have his work considered or compared to comics. He says he has made ‘comic-book type stories’ and they are ‘something

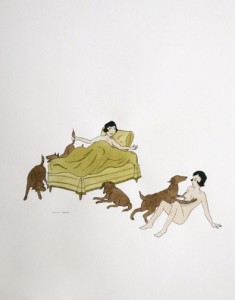

Marcel Dzama (b. 1974)

Untitled 2003

Ink and Watercolor on Paper

Marcel Dzama is known for his small-scale drawings, narrative in nature, sometimes including text. The worlds he creates are often sexual, violent, and dream-like. He uses a limited palette of warm browns, muted greens, and deep reds, reminiscent of turn of the century illustrations or antique children books. The content of these drawings are personal and controversial in a way unheard of in children’s illustration, although he admits he has been influenced by children’s literature. His work is dream like and the narratives are non-linear. (Baerwaldt) Although he is regarded as a fine artist and shows in gallery and museum contexts, his work has been reproduced in books and faux notebooks, has made its way onto album covers and even children’s books. Although Dzama, like Pettibon, sees a distinction between art and comics, and situates himself on the fine art side, his work is visually similar to comics and illustration, and has certainly influenced many young artists using illustrative elements and narrative possibilities.

Pettibon and Dzama represent artists who have used the conventions of comics and illustration as a means to expression characteristic of fine art. Because of the intention of these artists, their work has been situated in gallery and museum contexts. However, there are many benefits of making work for books and reproduction, and as young artists are less fearful of being associated with ‘comics’, they are utilizing cheap and accessible avenues to reach their audiences. The following artists, all under the age of 30, situate themselves in the context of comics without apprehension, and create work that appears visually less conventionally associated with comics.

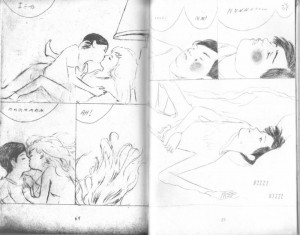

Blaise Larmee (b. 1985)

Excerpt from Young Lions 2009

Pencil on Paper

Blaise Larmee is a young comic book artist who published his first comic book, Young Lions after winning the prestigious Xeric grant. He helped run a comics blog ‘Comets Comets’ featuring art from other young and emerging comic artists that concerned itself primarily with ‘what making art means’. Larmee’s work could be considered ‘online performance art’, and his work sometimes includes long essays (sometimes in comic form, sometimes not), addressing issues of form, content, and youth-internet culture. (Collins) Larmee’s unwavering self-identification as a comics artist does not deter him from making highly conceptual, abstract, or ephemeral work, and continues to be at the forefront of the radical transformations occurring within the progressive comics community.

Aidan Koch (b. 1987)

Excerpt from Man From the North

Featured in Brad Trip

Pencil on Paper

Larmee created the small press ‘Gaze Books’ for the sole purpose of publishing the work of his friend and comics artist Aidan Koch. Koch’s dreamy, painterly comics are often ambiguous, quiet, and beautiful. Her process is unconventional in the world of comics. She rarely plans a page ahead of time. Instead, she lays down imagery together, in a non-linear manner, switching back and forth between panels and over the page. Although she works from notes, she isn’t interested in creating a readable story or plot line. She aims to create a tone, an ‘immersive experience’, and sites fine art and literature as a greater influence than comics. Her work may not appeal to the typical comics reader, but she states she “loves talking and thinking about comics as a progressive format”. (Collins)

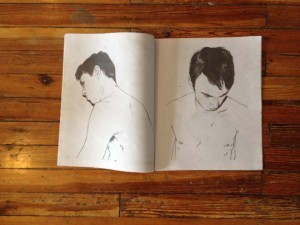

Anthony Cudahy (b. 1989)

Excerpt from Where Do You Go To

Pencil on Paper

Anthony Cudahy is a Brooklyn based artist, working mostly in pencil and oil paint. He creates single images, mostly of figures, sometimes abstracted or obscured. His work looks conventionally like that of a gallery artist, but he has created many zines and often puts his work in the context of print. He associates himself with comics artists, and his work often shows up in comics anthologies and festivals. He says when making a zine, he creates images with sequence in mind, and believes that putting them together in this format allows them to “give each other weight and structure through association”. (Griffiths)

These artists, along with many others, are exploring the creative potential of comics formats, by distributing their work in books, combining words and pictures, or creating visual poetry through sequential imagery. As artists broaden what is typically thought of as comics and infuse it with new intentionality, the gap between comics and art narrows and intertwines. And for the future of comics? Anthony Cudahy addresses young artists directly when he says, “Try not to limit yourself or label yourself. You are not a brand. That’s a big thing in schools right now- teaching people how to brand themselves to optimize their earning potential. I personally would like to see people fight this.” (Griffiths)

Bibliography

Baerwaldt, Wayne, and James Patten. Drawings by Marcel Dzama: From the Bernardi Collection. Windsor, Ont.: Art Gallery of Windsor, 2004.

Collins, Sean T. “Aidan Koch!” The Comics Journal. The Comics Journal, 17 Dec. 2012. 17 Dec. 2013.

Collins, Sean T. “Blaise Larmee!” The Comics Journal. The Comics Journal, 10 Mar. 2011. 17 Dec. 2013.

Gravett, Paul. Cult Fiction. Southbank Centre, UK: Hayward, 2007.

Griffiths, Daniel. “Featured Artist: Anthony Cudahy.” BITE Magazine. Bite Magazine, 8 Feb. 2012. 17 Dec. 2013.

Storr, Robert, Raymond Pettibon, Dennis Cooper, and Ulrich Loock. Raymond Pettibon. London: Phaidon, 2001.