By Elisabeth Pulido, grad student MICA’s MFA Illustration Practice, Fall 2013, Critical Seminar Final Paper

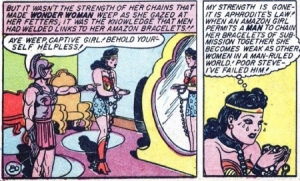

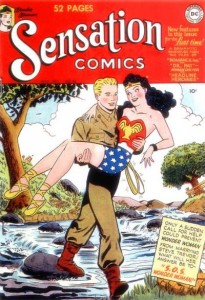

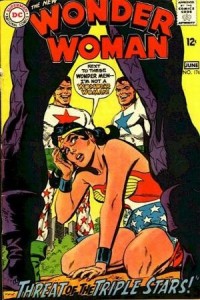

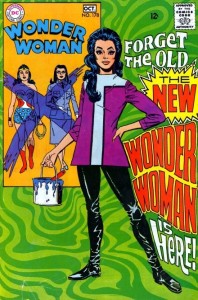

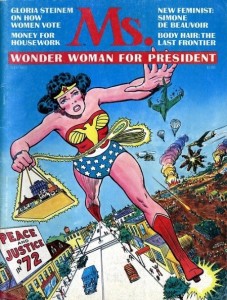

As super heroines go, they’ve always had a difficult time separating themselves from the sexism of their era either through ridiculous weaknesses, gender role quandaries, and character delegation as either Nymphs, Amazons or Madonnas. They’re supposed to epitomize female empowerment, yet they can never escape their own objectification. No one has had a harder time with this dichotomy than Wonder Woman, which makes her the perfect showcase of changing and contradictory views and opinions of women and their role in American society. Today taken as a symbol of female empowerment and feminism, and truly novel at the time of her inception for being a female heroine with her own series, her portrayal has continued to vacillate between progressive and backward since her inception. Maxwell Charles Gaines (publisher for All-American Comics at the time) read an interview in the October 25th issue of Family Circle with psychologist William Moulton Marston, famous for inventing the forerunner to the polygraph, entitled “Don’t Laugh at the Comics” which discussed the untapped potential of the genre.[ii] Gaines, intrigued by what he read, hired Marston on as an educational consultant to All-American and their sister company DC Comics. It was then that Marston saw his chance to create a super hero who didn’t win necessarily by fists and brute strength – but with human emotion, and more importantly, love to not just defeat her enemies but change their nature from good to evil. Marston passed the idea by his wife Elizabeth who said, “Fine, but make the character a woman.”[iii] And thus, Wonder Woman was born along her deep seated issues related to her gender. Wonder Woman’s origins set her up as an Amazon warrior-princess who leaves her paradisiacal island for the love of an American man she saves from a plane crash – and to join Man’s battle against the Nazis for justice. But really, mostly for the man. Super powered in terms of combat, Wonder Woman is also armed with the Lasso of Truth (anyone who is bound in it is forced to speak honestly), a tiara boomerang, and indestructible bracers. Yet, like most super heroes of the time, she had a weakness: bondage. Not just any bondage, she had to be tied up by a man.[iv] Whereupon she becomes powerless, unable to escape, and emotionally defeated. William M. Marston, and Harry G. Peter. Wonder Woman 1, no. 2 (January 1943). This weakness, revealed in the second issue of Wonder Woman, is truly baffling – until one looks back on Marston and his life. William Moulton Marston lived a polyamorous life, his home featured two women (one was his wife, the other his former research assistant who wrote the very article that interested Maxwell Charles Gaines into hiring Marston), four children (a pair from each), and engaged in bondage and submission sexual activities with both of his lovers. Marston believed that love really was about bondage and submission, and that, This … is the one truly great contribution of my Wonder Woman strip to moral education of the young. The only hope for peace is to teach people who are full of pep and unbound force to enjoy being bound … Only when the control of self by others is more pleasant than the unbound assertion of self in human relationships can we hope for a stable, peaceful human society. Giving to others, being controlled by them, submitting to other people cannot possibly be enjoyable without a strong erotic element.[v] Marston openly admitted Wonder Woman was “psychological propaganda,” a vehicle to push his views on the roles of women, domination, subjugation, and eroticism into the American psyche.[vi] William M. Marston, Harry G. Peter, and Sheldon Mayer. “Girls Under the Sea.” Sensation Comics 1, no. 35 (November 1944). Marston also goes on to state a massive blanket statement about the female gender, “Women are exciting for this one reason — it is the secret of women’s allure — women enjoy submission, being bound. This is why I bring out in the Paradise Island sequences where the girls beg for chains and enjoy wearing them” (see above).[vii] While one could interpret all of this as William Moulton Marston’s efforts to sever himself and his future world from what he saw as the prudishness of the past and an open acceptance of fetishism, her weakness can also be interpreted as a blatant patriarchal metaphor. Women are only bound to the power they give their patriarchal society. Marston’s Wonder Woman isn’t all eroticism, she is also symbolic of the growth of women understanding their own power and ability to participate in the work of the world rather than stay in their female-centric sphere. Wonder Woman, like the women in the 1940s who began transitioning into the workforce to aid in the war effort, leaves her domestic circle of Paradise Island to not just help the man she loves, but correct the wrongful bondage of the nations and peoples involved in World War II through war. She leaves a place of safety, where her role is known to exert her influence on the outside world that needs her. BDSM tendencies and weaknesses aside, she is truly capable, strong, and makes her own decisions about how she should act. Marston himself acknowledges as much: Prior to the first World War nobody believed that women could perform these feats of physical strength. But they’re performing them now and thinking nothing of it. In this far worse war, women will develop still greater female power; by the end of the war that traditional description ‘the weaker sex’ will be a joke – it will cease to have any meaning.[viii] William Moulton Marston hoped deeply for the world to recognize the strength of women through their war efforts and his Wonder Woman comic strip. He didn’t wish for one gender to be seen weaker than the other, but to be seen as they are – different, but capable, and adept at binding one another other with their actions and emotions rather than physical chains. It is after Marston’s death in the 1947, the end of World War II, and the subsequent return of men back into the workforce, that Wonder Woman is passed around from editor to editor without much success. They are faced a difficult task: how to use Wonder Woman and all she stands for as a medium to help transition the American female populace back into the domestic sphere, and out of the dangerous action of a “man’s world” but still keep her a powerful individual. In an attempt to do so, writer Robert Kanigher goes out of his way to write Wonder Woman as a series romantic stories and interludes, with short bursts of action to keep his audience interested. Robert Kanigher, Harry G. Peter, Irwin Hasen, and Bernard Sachs. “S O S. Wonder Woman.” Sensation Comics issue number 94 is the best example of this transition from action to romance (see above). As evidenced by the cover, Wonder Woman has ceased to be an all-consuming agent of justice, but is instead a dainty woman being carried across a shallow stream because her love interest, (who at this time remains Captain Steve Trevor) can’t bear to let his sweetheart’s golden bondage stilettos get wet. The sun is shining, the scene is ideal complete with flowers and fluffy cotton ball clouds, and the two lovers, free from the toils of war can now blush innocently and gaze into each other’s eyes. Within this issue Steve proposes to Wonder Woman and she accepts under one condition – that she not be needed for a single day. Steve tries his best to keep her safe from the action, but due to her strong sense of responsibility and refusal to let the local police handle a local gang, Wonder Woman woefully rejects the proposal and tells him marriage will only happen when she is no longer needed. One thing of note here is Wonder Woman’s demotion from Nazi-plot-destroyer to local-gang-subduer. As one can imagine, this struggle to decide the theme of Wonder Woman as either a bondage-fueled super hero saga or teary romance comic deeply affected Wonder Woman’s readership. Purchased by a staggering majority of male readers, this new direction failed to resonate with them. This demographic wasn’t interested in her romantic foibles and scruples, they wanted to see her get back in the action, but not in the place of a man. This tussle with gender roles and the expectations of its target market continued to plague the character for the next twenty years. It’s this struggle to make Wonder Woman a heroine and still force her into the gender roles of her time that makes D.C. Comic’s Wonder Woman, issue 176 published in June 1968 and written by Robert Kanigher so fascinating. Three triplets vie for Wonder Woman’s attentions, but they’re weak and not that attractive, so she doesn’t give them the time of day. However, when they are given a super hero serum from a mysterious scientist and become beefcake hunks, they manage to pique Wonder Woman’s interest. This happens just in time to protect her from the dreaded date of June 18th – the one day a year she loses her powers. While she refuses to fall for any of them, Wonder Woman drawn to their newfound animal magnetism in her moment of powerlessness. Yet when their powers (and hunkiness) from the serum disappear and she regains her powers to save the day, she rejects them all, and states that she must return to her role as the lone Amazon heroine and will not consider marriage until her life of fighting crime comes to a close. In short, Wonder Woman when removed from her powers becomes nothing but an ordinary woman who must rely on men to protect her and is drawn to them out of her own powerlessness. However, when restored to her super human self, she must return to the role of the loveless, but powerful Amazon. That’s like saying that powerful women who chose to use their strengths will always be incomplete because they don’t have a man and they won’t ever get one until they let their power go or have it taken from them forcibly. Robert Kanigher, Irv Novick, and Mike Esposito. “The Threat of the Triple Stars!” Wonder Woman’s power or value as an individual is defeated just by the composition of this cover alone (see above). Crumpled to the ground, barely holding herself up, surrounded on all sides by large strapping men grinning at their masculine prowess, we find Wonder Woman looking up at the massively muscular man in front of her. Her position of subjugation and helplessness is amplified by the usage of perspective and framing of the third male’s beefy calves and thighs to overshadow and tower over her completely. Her relatively primary colored palette is overcome with the commanding purple shadow of the one man in the forefront. Better yet, one cannot help but notice the strategic placement of the “N” in the Wonder Woman title, and Wonder Woman’s own words of self-abasement. There really isn’t any other conclusion we can come to. Dennis O’Neil, Mike Sekowsky, Dick Giordano, and Jack Miller. “Wonder Woman’s Rival.” Wonder Woman 1, no. 178 (October 1968). No less than three issues later is Wonder Woman completely revamped and the comic put under the name of her human pseudonym, Diana Prince. Denny O’Neil and Mike Sekowsky depower Wonder Woman entirely because she refuses to leave “Man’s World” and return with the rest of her Amazonian tribe to another dimension to build their magical powers. So instead of helping win wars or fight crime with her godlike abilities, she becomes a mod boutique owner fighting bouts of crime with her hand-to-hand combat skills taught to her from her martial arts mentor, a man named I-Ching. O’Neil and Sekowsky were under the impression that depowering Wonder Woman would elevate her as a revolutionary feminist icon, presenting her as everything an ordinary woman could be and do with intense training and focus.[ix] However, this is not how the series was received. Feminist icon Gloria Steinem flat out disparaged and criticized the reboot, denouncing its creators for stripping the female protagonist of her powers, and place at the source of her newfound abilities a male mentor.[x] Gloria Steinem and unknown artist. Ms. Magazine 1, no. 1 (January 1972). Steinem’s dislike for the reboot went so far that when she published her first issue of Ms. Magazine (a feminist publication still in circulation today) in January 1972, she put Wonder Woman on the cover itself, and inside the magazine’s pages condemned her present representation. This article, in conjunction with a few years of harsh denunciation and condemnation are responsible for DC Comics to reversion of Diana Prince back into the Amazonian warrior of her origin and reinstate her as Wonder Woman. But where is Wonder Woman now, one might ask? Right where she’s always been. She remains a character born from a deep inner disparity struggling with her gender role, her readership, and how she is perceived by the public. She remains an outsider looking in on a man’s world, both in what she does (despite the growth of the number of female super heroes in the past fifty years), and what she is (an Amazonian goddess). Wonder Woman is beset with opposing problems. She’s too independent for a man to find her appealing, too dependent upon love interests as motivation.[xi] She’s too covered up for the modern man, yet too exposed to appease the women who might support her. As Wonder Woman and Diana Prince, she remains, as always, empowered but objectified. Bibliography Armitage, Hugh. “Wonder Woman: The Many Faces of DC Comics’ Princess Diana.” Digital Spy. December 11, 2013. Accessed December 15, 2013. https://www.digitalspy.com/comics/news/a537570/wonder-woman-the-many-faces-of-dc-comics-princess-diana.html. Daniels, Les, and Chip Kidd. Wonder Woman: The Golden Age. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2001. 67. Ham, Randall. “From Amazing Amazon to Feminist Icon.” Wonder Woman. Accessed December 15, 2013. https://astro.temple.edu/~alower/ww/. Hundall, James. “Wonder Woman Reboot: Strident Feminism Is the Problem, Not the Costume.” Breitbart News Network. July 2, 2010. Accessed December 15, 2013. https://www.breitbart.com/Big-Hollywood/2010/07/02/Wonder-Woman-Reboot–Strident-Feminism-Is-the-Problem–Not-the-Costume. Joyce, Nick. “Wonder Woman: A Psychologist’s Creation.” American Psychological Association 39, no. 11 (2008): 20. Accessed December 15, 2013. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2008/12/wonder-woman.aspx. Kanigher, Robert, Harry G. Peter, Irwin Hasen, and Bernard Sachs. “S O S. Wonder Woman.” Sensation Comics 1, no. 94 (October 1949). Kanigher, Robert, Irv Novick, and Mike Esposito. “The Threat of the Triple Stars!” Wonder Woman 1, no. 176 (June 1968). Lamb, Marguerite. “Who Was Wonder Woman?” Bostonia: The Alumni Quarterly of Boston University. July 20, 2006. Accessed December 15, 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20071208045132/https://www.bu.edu/alumni/bostonia/2001/fall/wonderwoman/. Lyons, Charles. “Suffering Sappho! A Look at the Creator & Creation of Wonder Woman.” Comic Book Resources Page Not Found. August 23, 2006. Accessed December 15, 2013. https://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article. Marston, William M., and Harry G. Peter. Wonder Woman 1, no. 2 (January 1943). Marston, William M., Harry G. Peter, and Sheldon Mayer. “Girls Under the Sea.” Sensation Comics 1, no. 35 (November 1944). “Myth Understood: Wonder Woman: Feminist Icon or Exploitative Fantasy? Part 1.” Comic Book Movie. September 2, 2012. Accessed December 15, 2013. https://www.comicbookmovie.com/fansites/betaraysyr/news/?a=66698. O’Neil, Dennis, Mike Sekowsky, Dick Giordano, and Jack Miller. “Wonder Woman’s Rival.” Wonder Woman 1, no. 178 (October 1968). Richard, Olive. “Our Women Are Our Future.” Family Circle, August 14, 1942. Accessed December 15, 2013. https://www.castlekeys.com/Pages/wonder.html. Steinem, Gloria. Ms. Magazine 1, no. 1 (January 1972). “Wonder Woman.” Castle Keys. Accessed December 15, 2013. https://www.castlekeys.com/Pages/wonder.html. _____________ Endnotes

Sensation Comics 1, no. 94 (October 1949).

Wonder Woman 1, no. 176 (June 1968).