Presidents, Politics, & the Pen: The Influential Art of Thomas Nast

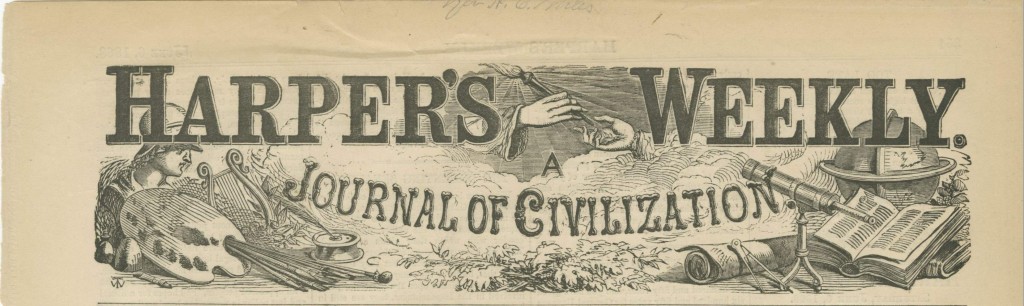

Known as the “Journal of Civilization,” Harper’s Weekly was an American political magazine published in New York from 1857-1916. The magazine was hugely popular thanks to its extensive use of illustrations and its broad editorial content. By the end of 1861, Harper’s had a circulation of 120,000, and was one of the leading magazines of the Civil War period. A liberal, progressive paper, Harper’s supported President Abraham Lincoln, the preservation of the Union, and the Republican Party, perspectives that editorial cartoonist and caricaturist Thomas Nast (1840-1902) also held strongly. Nast joined the staff of Harper’s in 1862, and rose to prominence for his Civil War battle front depictions.

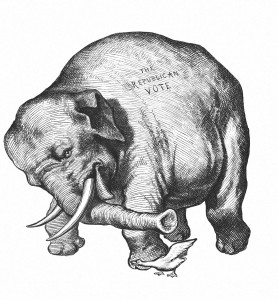

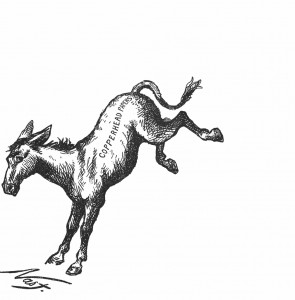

With Harper’s as his platform, Nast effectively used satire and masterful caricatures to hold candidates accountable for the issues of the day, which included the economy, political corruption, immigration, and civil rights. Although Nast lacked formal education, he was extremely adept at incorporating allegorical, symbolic, and literary references into his detailed pictures as a way to explain complex, political issues to Harper’s readers. His representations of the donkey and elephant helped to solidify these images as enduring symbols for the Democratic and Republican Parties, respectively.

Known as “The President Maker,” Nast’s persuasive, and sometimes scathing cartoons proved crucial in influencing the nation’s vote and affecting the outcomes of six presidential elections between 1864 and 1884. His illustrations supported the causes he believed in and the candidates he thought were best. As these works reveal, though the names on the ballots have changed, the issues that Nast brought to light remain surprisingly similar and relevant more than 100 years later.

The Election of 1864: Abraham Lincoln v. George McClellan

The presidential election of 1864 was one of the most important in American history. It took place in the Union states during the third year of the Civil War. Lincoln’s bid for re-election was in doubt due to huge Union war losses and opposing conservative party opinion regarding the Emancipation Proclamation and the abolition of slavery. Although the Democratic nominee George McClellan shared a hardline view against the Confederacy, Republicans viewed him as an appeaser who wanted to compromise with the South at the expense of the Union. Lincoln was victorious, but sadly, President Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth seven weeks into his second term.

This is one of Thomas Nast’s most powerful and effective illustrations, which was reprinted widely by the Republicans in their effort to have Lincoln re-elected. It was widely considered to have played a crucial role in turning the tide of the campaign toward Lincoln’s favor and simultaneously propelled Nast to widespread fame.

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)

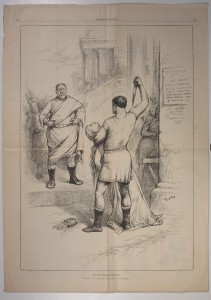

Compromise with the South

Harper’s Weekly, September 3, 1864, p. 572

Wood engraving on paper

Nast was a fierce supporter of the Union cause and this illustration is a classic example of his skillful use of allegory and melodrama to express his opinion and to support the cause he believed in. The image criticizes the Democrats’ party platform, and its proposed cease-fire and negotiated settlement with the South. The scene shows Columbia weeping at the grave of a Union soldier. A disabled Union soldier shakes hands with Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy. In the upper left, the American flag is hung upside down as a signal of distress.

The Election of 1868: General Ulysses S. Grant v. Horatio Seymour

Andrew Johnson succeeded Lincoln after his assassination but did not receive the Republican nomination. Instead, the Republicans chose as their nominee, war hero General Ulysses S. Grant. The Democrats chose former New York governor, Horatio Seymour, who opposed giving equal protection and voting rights to freed slaves and African-American citizens.

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)

Grant in Chicago

Harper’s Weekly, June 6, 1868, cover

Wood engraving on paper

In this illustration, General Ulysses S. Grant is heralded by Thomas Nast as the Republican presidential nominee. Nast revered and idolized Grant and only portrayed him in the most flattering light. Nast’s opinion of Grant was shared by the party who described him as “a man whose fidelity, simplicity, sagacity, honesty, and persistence have all been displayed in the most illustrious career of the time.”

The Election of 1872: General Ulysses S. Grant v. Horace Greeley

President Grant was easily re-elected to a second term in office. This was achieved in spite of a split within the Republican Party that resulted in a third party of Liberal Republicans nominating Horace Greeley, the long-time editor of the New York Tribune, to oppose Grant. This action caused the Democratic Party to cancel its convention and support Greeley without nominating a candidate of its own.

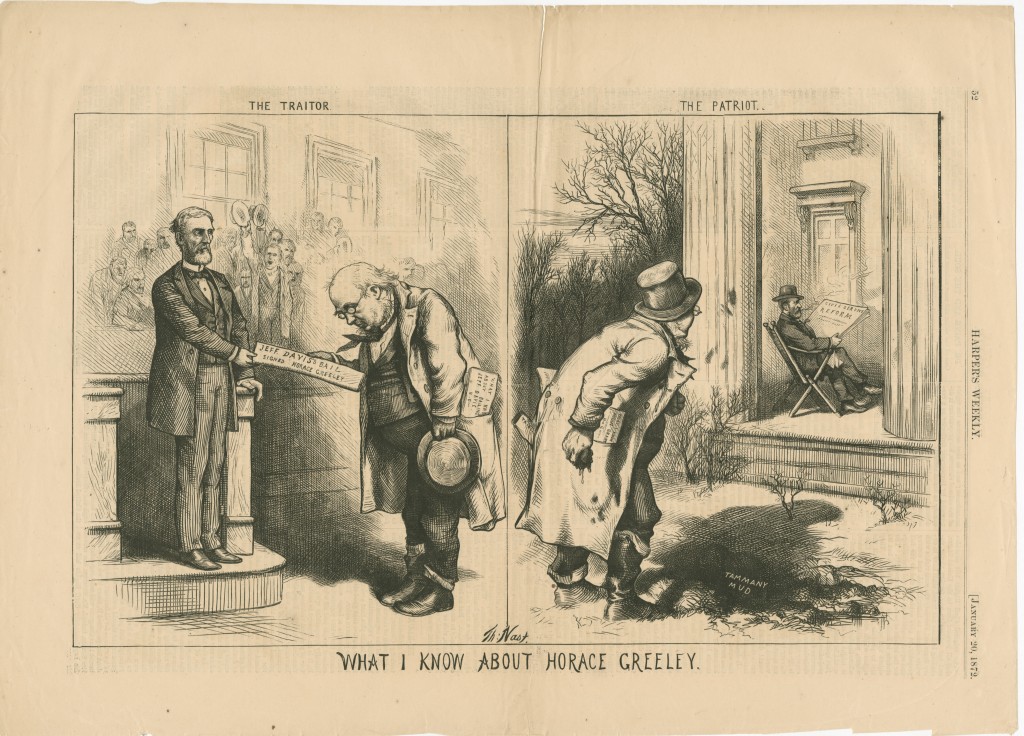

Thomas Nast was relentless in his attacks on Greeley and created a series of disparaging cartoons called “What I Know About Horace Greeley.” Greeley lived on a farm about 35 miles north of New York City, where he applied experimental scientific methods to agriculture. In 1871, he published a book called What I Know of Farming. Nast played on the title to mock Greeley’s perceived pretense of being an expert on various subjects.

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)

What I know about Horace Greeley

Harper’s Weekly, January 20, 1872, p. 52

Wood engraving on paper

In this illustration, Greeley “The Traitor” bows humbly to former Confederate President Jefferson Davis while presenting bail in a Richmond courtroom. The image serves to remind readers of Greeley’s controversial action, in 1867, to secure a bond for Davis’ release from federal prison. Alternatively, Greeley “The Patriot” prepares to sling “Tammany Mud” at President Grant, who sits on the White House porch.

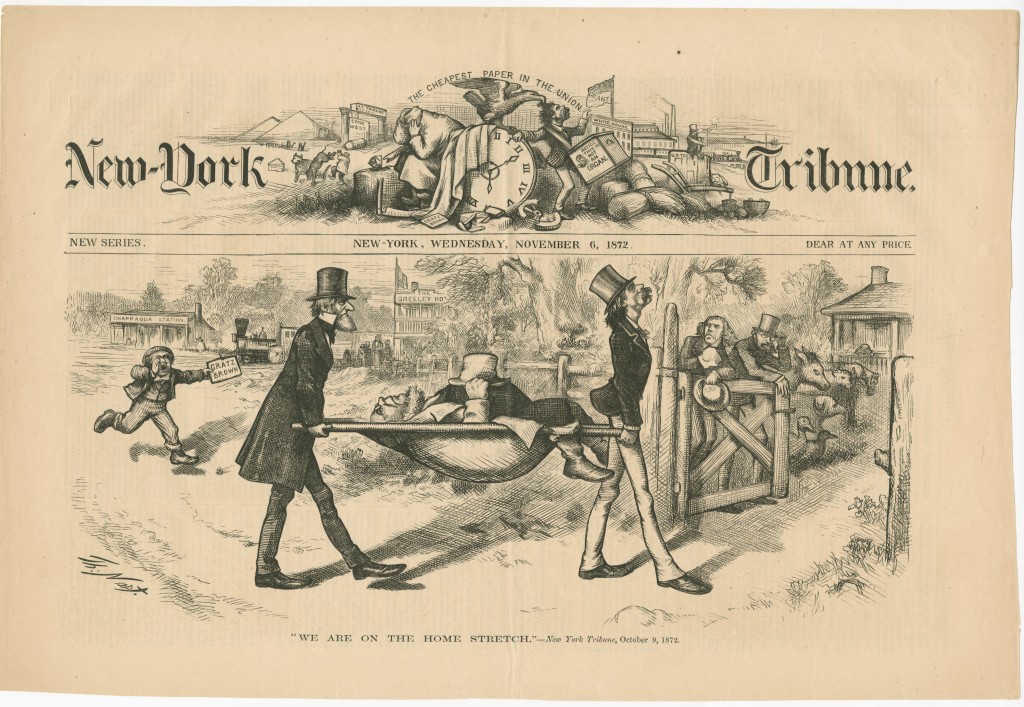

The most controversial image of the 1872 campaign was published two weeks before the election. A recent editorial in Horace Greeley’s former newspaper the New York Tribune had projected triumph for the candidate, proclaiming, “We are on the home stretch, with every prospect of success.” Nast seized the opportunity to create yet another witty but ironic play on words. The result was an illustration that re-imagined the Tribune front page, including a parody of the newspaper’s masthead. Greeley is depicted arriving at his Chappaqua, New York farm the day after the election, carried on a stretcher.

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)

We Are on the Home Stretch

Harper’s Weekly, November 2, 1872, p. 848

Wood engraving on paper

On November 29, 1872, after the popular vote was counted, but before the Electoral College cast its votes, Greeley died. His wife had died just a month earlier. Some thought that the abuse suffered at the hand of Nast and Harper’s contributed to their untimely demise. Greeley received three posthumous electoral votes, but they were disallowed by Congress.

The Election of 1876: Rutherford B. Hayes v. Samuel Tilden

The 1876 election was one of the most controversial in United States history. Samuel Tilden, the Democratic candidate, won the popular vote, 51 to 48 percent, but with only 184 electoral votes, was one short of an Electoral College majority. Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes collected just 165 electoral votes, and the 20 remaining votes were in dispute. One vote was from Oregon and 19 were from the three southern states, which still retained a federal military presence under Reconstruction governments: South Carolina, Florida, and Louisiana.

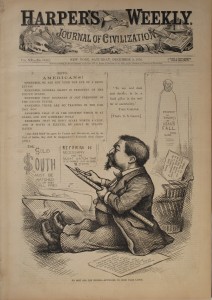

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)

No Rest for the Wicked

Harper’s Weekly, December 2, 1876, cover

Wood engraving on paper

With the election results still in dispute, Nast depicts himself preparing for more work in support of the Republican Party in this cartoon.

The Constitution did not provide for the unprecedented scenario of a disputed presidential election, so a 15 member bipartisan commission was created to resolve the conflict. The commission commenced hearings on February 2nd and continued until March 2nd. In the end, Hayes received all 20 contested ballots, allowing him to win the presidency by one electoral vote, 185 to 184.

The Election of 1880: James Garfield v. General Winfield Scott Hancock

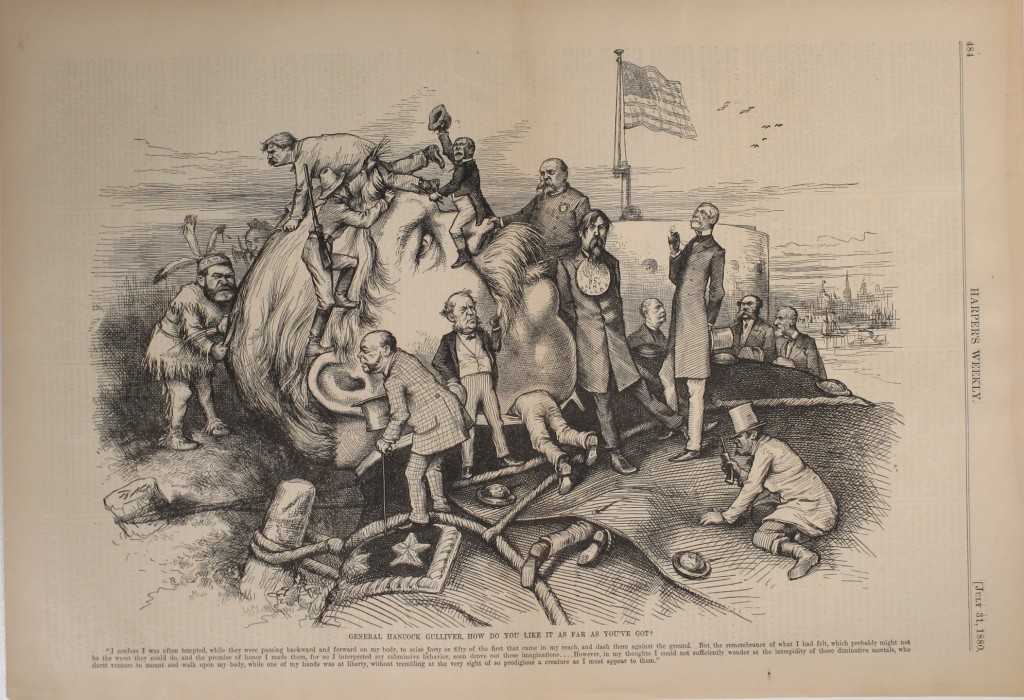

When creating political cartoons, Nast faced the dilemma of maintaining his personal integrity. In this case, he admired General Winfield Scott Hancock’s service in the Union Army. Though he did not support Hancock’s party, Nast preferred not to malign the General’s reputation. When asked about his relationship with Hancock, Nast replied “The man, yes; his party, no.”

Conversely, Nast felt that it was hypocritical to endorse Garfield, although he still supported the Republican Party. He had depicted the presidential hopeful in a disapproving cartoon related to the 1873 Credit Mobilier scandal. The charge accused congressional members of exchanging political favors for undervalued Union Pacific Railroad stock.

In the end, Nast’s drawings lacked passion for either candidate. His renderings defended the Republican platform by drawing negative images of the Democratic Party, avoiding direct attacks on Hancock. With fewer than 2,000 popular votes separating the candidates, Garfield won the Electoral College and became the 20th President of the United States. Tragically, he was assassinated six months after taking office, and was succeeded by Vice President Chester A. Arthur.

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)

General Hancock Gulliver, How do You Like it as Far as You’ve Got?

Harper’s Weekly, July 31, 1880, p. 484

Wood engraving on paper

In Nast’s cartoon, Harper’s readers would have instantly recognized his literary reference to the satirical work, Gulliver’s Travels, by Jonathan Swift (1667-1745). In Swift’s narrative, Gulliver washes ashore on the island of Lilliput, finding it populated with tiny citizens who are arrogant and self-righteous. Here, the Democratic presidential candidate Hancock is being tied down by members of his own party. By comparing Hancock to Gulliver, Nast does not attack Hancock directly but implies he is under the control of corrupt Democrats.

The Election of 1884: James Blaine v. Grover Cleveland

In 1884, the Republican Party divided into three major factions: Stalwart, Half-Breed, and Reform. The Stalwarts, including ex-President Grant, favored political machines and the spoils system. Half-Breeds, like former Secretary of State Blaine, supported civil service reform and a merit system. The Reformers, nicknamed Mugwumps, vehemently opposed the nomination of Blaine, due to his record of corruption, and left the party.

Long-time Republican Nast faced a moral decision, to support Blaine’s candidacy or join the liberal Mugwumps. In the July 21st issue of Harper’s Weekly, its publishers featured the Nast cartoon “Death Before Dishonor,” a dramatic visual on the Reformists’ position, and an editorial stating that “to support nominations which the moral judgment of the voters rejects, for the sake of the party, is to accept moral slavery….” Consequently, Nast and Harper’s were highly criticized and denounced as traitors by supporting the Democratic candidate, Grover Cleveland.

Thomas Nast (1840-1902)

Death Before Dishonor

Harper’s Weekly, June 21, 1884, p. 396-7

Wood engraving on paper

The Democratic candidate Cleveland won this election which ended the Republican Party’s stronghold of the White House since 1861.

To find out more about Thomas Nast and his political cartoons, visit the Norman Rockwell Museum for the exhibit Presidents, Politics, & the Pen: The Influential Art of Thomas Nast, on view through December 4, 2016.