By Diana Flores Blazquez, grad student MICA’s MFA Illustration Practice, Fall 2013, Critical Seminar Final Paper.

Sometimes our work is the way we find to explore fantasy lives and unimaginable worlds. Artists can have a realistic grounded discourse that can express whatever they want to share with the world, but there is always the possibility and flexibility to do it with irrational and invented shapes and subjects. There is always the chance to abandon reality and travel to a fantasy world in which it’s impossible to stay as long as needed.

Winsor McCay is an example of the artist’s capacity to delve into fantasy and to share it with his audience. He included his favorite depictions of fantasy and wonder into almost everything he created, from poster illustration, to animation, and even illustrated moral sermons. He seduced his audience to following him inside a world of childish fantasy and playfulness. McCay remembered childhood as a mixture of nightmares and dreams.His great skill was that he was able to illustrate an amazing likeness of what those nightmares and dreams felt like. Maurice Sendak, the famous American illustrator and writer, author of one of the most amazing children’s books of the 20th century,

Many artists after McCay were influenced by his creations. He was a pioneer in animation, a branch of art that was still developing. Although he mistakenly named himself the inventor of animation, he is a crucial part of animation history. He solved a variety of technical issues and created methods that were inventive in this burgeoning field. He did the same in his comic strips, where he broke the known rules and explored possibilities of transforming conventional methods of expression into tools that enhanced the feeling of awe and wonder for the viewer. Strangely so, he wasn’t very well known until a few years ago, and he doesn’t share the fame that some of his peers still have, such as Walt Disney or Otto Messmer. Little Nemo is never considered in the same league as Mickey Mouse or Felix The Cat.

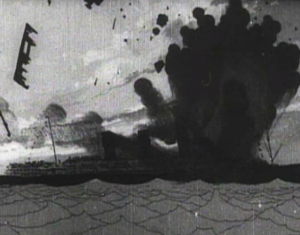

This lack of fame may be due to Winsor’s shyness, his preference for privacy, and his disregard of the press and popular media. He believed that animation and illustration where both forms of arts, and as such, should be treated with patience, and meticulousness that they deserved, –instead of focusing on the work as a mass-produced and sellable object. He never made much money out of his work, and when he did, he spent it. He wasn’t making art to become a rich man; he was drawing and animating because he enjoyed it. He even drew the 12,000 frames needed to animate one of his short films The Sinking of the Lusitania himself, with only two assistants who helped him with the photographing and background alignments of each celluloid frame.

McCay always enjoyed making art. No matter what the outcome or how famous he became; he was one of the most important and influential artists of our times.

“The one constant in the contradictory and hectic life of Winsor McCay was his implacable love of drawing . . .. The physical act of putting pencil or pen on paper filled McCay with a joy experienced only by other graphic artists.”[3.]

Winsor McCay n

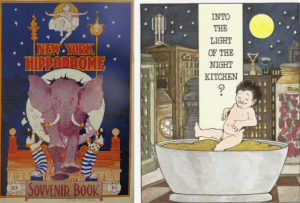

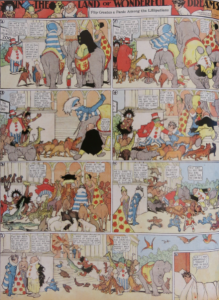

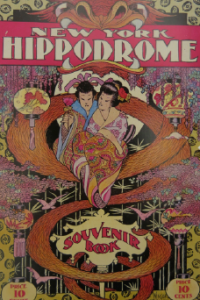

Winsor McCay n ever studied art at an art school. He moved to Chicago when he was twenty-two years old and found a job as an apprentice at the National Printing and Engraving Company. They specialized in printing for shows, commercial, and for the railroad. They worked particularly in circus posters, which helped to define McCay’s aesthetic. You can see the influence of those illustrations of circus creatures and wonders on his later illustrations, such as the ones he made for the 1908 cover of the New York Hippodrome’s program. They have the aura of the circus along with an air of magical exoticism the detailed ornamentals give these scenes. His interest in the representation of fantasy worlds and characters is present from his beginnings. His style was adopted and developed when he was young, and he barely changed it through the years. If we compare his posters from the early 1900’s with his final pieces for The Land of Wonderful Dreams from 1914 we still see the same amount of detail, the fine line, and the strong art nouveau style strokes he used throughout his life.

ever studied art at an art school. He moved to Chicago when he was twenty-two years old and found a job as an apprentice at the National Printing and Engraving Company. They specialized in printing for shows, commercial, and for the railroad. They worked particularly in circus posters, which helped to define McCay’s aesthetic. You can see the influence of those illustrations of circus creatures and wonders on his later illustrations, such as the ones he made for the 1908 cover of the New York Hippodrome’s program. They have the aura of the circus along with an air of magical exoticism the detailed ornamentals give these scenes. His interest in the representation of fantasy worlds and characters is present from his beginnings. His style was adopted and developed when he was young, and he barely changed it through the years. If we compare his posters from the early 1900’s with his final pieces for The Land of Wonderful Dreams from 1914 we still see the same amount of detail, the fine line, and the strong art nouveau style strokes he used throughout his life.

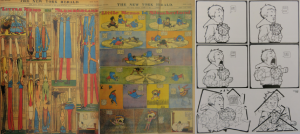

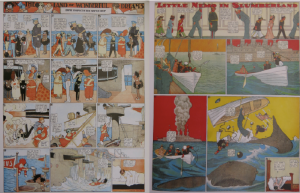

“As a strip cartoonist, Winsor McCay was a blessing to the new art form. He established fantasy as a dominant theme and set graphic standards that helped establish the form in its protean days.”[4.] Not only with regards the theme, but also in their visual composition and experimentation, Little Nemo in Slumberland and Sammy sneeze both had amazing experiments running through their comic frames. The borders of each page were sometimes enlarged, or widened. They might even be broken and squashed. But these manipulated edges would be as unimportant as compared to the boundaries of McCay’s imagination.

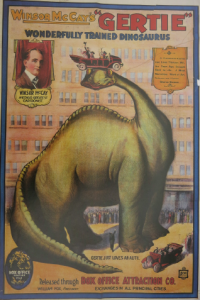

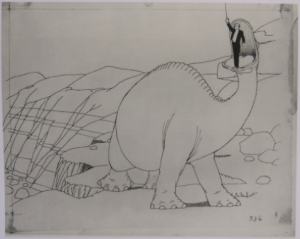

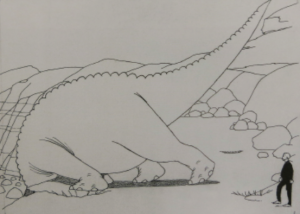

Over time the comic strip stopped serving the purpose of experimentation, and by 1914 McKay’s interest was focused on the new promises of his current projects in animated film. He wanted to work on the animation of Gertie, the Dinosaur. This would become part of his vaudeville act, which was one of the first multimedia performances in art history.

He was a pioneer of this branch of art, and believed that animation was the future of illustration and still images. “Take a good look ahead, the time is coming when people will not be content to view merely a stationary picture . . .. People are soon going to be educated to such degree that they will not be interested in pictures that stand still.”[5.] Due to his growing interest in exploration of moving images, McCay began to pay less attention to his comic strip that was now committed to do on a weekly basis by his boss, William Randolph Hearst. Hearst played an important role in McCay’s work, since his interest was always on his paper’s editorial illustrations and not on sponsoring new projects in visual fields that were still undeveloped. McCay’s retitled version of Little Nemo was uninteresting and flat compared to his previous works.

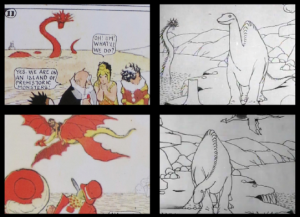

McCay concentrated on developing characters for his new animated projects, as can be seen in a few of the final strips in which Nemo travels to the land of the Antediluvians and encounters a bunch of dinosaur-like creatures. He even started experimenting with names for his dinosaur character, calling these creatures Tessie, Bessie and Bertie. All of these are examples that indicate that the main interest of an artist may be found looking deep into layers of his commissioned work. The way McCay managed to work around his obligations was remarkable. Even though the themes of his work weren’t the same and sometimes they might be less exciting, he managed to keep the quality of the strip running for one more years while also working on Gertie. “Sometimes McCay revealed within his assigned work where his true interest lay.” Even in McCay’s last strips he was developing his new character, and also the artistic background and storyline. There is one comic strip from December of 1913, titled Flip, Impie, Diplodocus and a fish! in which McCay starts practicing perspective for the background scenes of Gertie. He even makes the dinosaur turn to the lake and look down at the water in the same way Gertie does in the later movie. Instead of throwing rocks as she does in the animation, she throws the fish, Flip and Impie into the lake in the still figures.

McCay concentrated on developing characters for his new animated projects, as can be seen in a few of the final strips in which Nemo travels to the land of the Antediluvians and encounters a bunch of dinosaur-like creatures. He even started experimenting with names for his dinosaur character, calling these creatures Tessie, Bessie and Bertie. All of these are examples that indicate that the main interest of an artist may be found looking deep into layers of his commissioned work. The way McCay managed to work around his obligations was remarkable. Even though the themes of his work weren’t the same and sometimes they might be less exciting, he managed to keep the quality of the strip running for one more years while also working on Gertie. “Sometimes McCay revealed within his assigned work where his true interest lay.” Even in McCay’s last strips he was developing his new character, and also the artistic background and storyline. There is one comic strip from December of 1913, titled Flip, Impie, Diplodocus and a fish! in which McCay starts practicing perspective for the background scenes of Gertie. He even makes the dinosaur turn to the lake and look down at the water in the same way Gertie does in the later movie. Instead of throwing rocks as she does in the animation, she throws the fish, Flip and Impie into the lake in the still figures.

The movements are even very similar to the ones on the multiple plates of the animation. In An alarm of fire among the antediluvians, a diplodocus at the top of a cliff stands in its hind legs just as Gertie does when she dances for McCay in the film, and in Flip in the Land of the Antediluvians we can see both the flying four winged lizard and the water snake that also appear on the short animation.

It is interesting to see how McCay continued to include the diplodocus character into the strips, even when he was supposed to make a Christmas-themed strip.

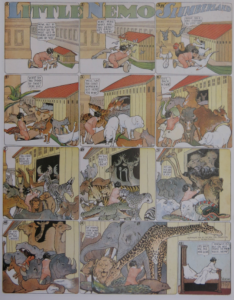

He put Tessie into reindeer attire, the sleigh carrier, and also added the throwing action to it that we have seen repeated multiple times in various scenes. All of these examples show how while working on commission pieces Winsor could still focus on what interested him within these pieces. He still developed new characters, with new personalities, abilities and traits. Without anybody realizing, he made the Sunday American his personal sketchbook as he developed the characters and storyline for his film projects. And even though, the strips became less exciting and daring, and less about the breaking of conventional forms and comic rules, they still played with McCay’s incredible ideas of perspective and worlds of fantasy. He still played with concepts of size contrasts and the extensive detailing of all elements. The strip Flip Creates Panic among the Lilliputians shows a large variation in sizes among animals of many kinds.

A large group of what appears to be baby animals, but that in fact are a Lilliputian animal, escape from the zoo. This strip resembles one from Little Nemo in Slumberland from a few years before, in which Nemo tries to bring a stampede of animals back into an ark that starts out being really tiny and grows out of proportion and so do all the animals trying to escape from it. The detail of each animal is as impressive as always, but there is something new about the storyline. The main character of these last strips that McCay made for Hearst in 1913 was not Nemo anymore. Flip began to be a much more active character. “Gone was Nemo as protagonist; the questing boy who evolved as a character throughout the first version of the strip was now dull and passive.”[6.] Winsor always identified with Little Nemo; he was the physical incarnation of his connection between reality and fantasy. Little Nemo had to be the detonator of all imagination and dreams. It was through his character that McCay’s stories developed. The boy’s appearance was based on his son Robert McCay, but Nemo was actually McCay’s alter ego. “His Child-double acting out the artist’s fears and hopes, escaping into a world beyond drab reality.”[7.] Flip acted more as an adversary to Nemo, he wore the top hat labeled ‘Wake up’. He is the character that represents reality and who wants Nemo to be awake and live in reality and to act and obey conventional rules. As an antagonist Flip was very important because he helped to develop Nemo’s character. “Although a rival, Flip awakened in Nemo a generosity of spirit . . . his charitable qualities developed into Messianic tendencies.”[8.] Knowing this, it would seem obvious that this miraculous Christ-like figure would be missing from the last strips, where Winsor did not see himself as an important link between fantasy and reality. He saw these as practice opportunities, and as such completely attached to reality and thus, ruled by Flip, the character who best represented it. He transferred this magical presence, able to connect realty to fantasy to his own portrait in Gertie, where he acts as himself and interacts with the giant creature.

The performance was a tr emendous success, and Winsor enjoyed all the travel with the projection to different locations and performing his act accompanied by the charming diplodocus. During this period and the following years, McCay created various new animated films in which he explored new processes and techniques. He developed the celluloid drawings, that offered him the possibility of having a non-moving landscape in the background and only animating the story’s main figures. The Sinking of The Lusitania was hand painted in every frame, and the amazing effects it achieves are remarkable. For example, the movement of the smoke coming out of the chimneys of the ship is mesmerizing. It looks as if it was filmed rather than illustrated. Where McCay’s abilities reached their climax was with the creation of his 1921 short film The pet, also inspired by his own work on the Rarebit comics. This film is excellent in animation quality, and in its general subject. It deals with the uncontrollable growth of a pet that suddenly becomes a city crushing, building-devouring monster. It’s charmingly terrifying, and according to some authors “The first ever giant monster attacking a city’ movie ever made.”[9.] McCay’s short film inspired later kaiju movies and animations of many kinds.[10.]

emendous success, and Winsor enjoyed all the travel with the projection to different locations and performing his act accompanied by the charming diplodocus. During this period and the following years, McCay created various new animated films in which he explored new processes and techniques. He developed the celluloid drawings, that offered him the possibility of having a non-moving landscape in the background and only animating the story’s main figures. The Sinking of The Lusitania was hand painted in every frame, and the amazing effects it achieves are remarkable. For example, the movement of the smoke coming out of the chimneys of the ship is mesmerizing. It looks as if it was filmed rather than illustrated. Where McCay’s abilities reached their climax was with the creation of his 1921 short film The pet, also inspired by his own work on the Rarebit comics. This film is excellent in animation quality, and in its general subject. It deals with the uncontrollable growth of a pet that suddenly becomes a city crushing, building-devouring monster. It’s charmingly terrifying, and according to some authors “The first ever giant monster attacking a city’ movie ever made.”[9.] McCay’s short film inspired later kaiju movies and animations of many kinds.[10.]

These varied creations are the result of an enthusiastic artist exploring the various gradients of his practice. McCay’s life was ordinary like any other person’s and filled with the common and sometimes uncommon ups downs, turns and twists. Nevertheless he adapted his imagination and innovations to the developments of his time and evolve with it. He managed to give the world a taste of what the future was all about. Even today the work he produced sounds and feels very contemporary. It’s not only an inspiration for its visual qualities but also because McCay sought to have an artistic practice that was respected even as he shared his fantasies with the public. Although he didn’t want to keep things and processes to himself he was forced to patent his animation techniques and discoveries, just to protect himself from thieves.[11.] Obtaining money from his technological discoveries was never important for him. His way of seeing into the future and keeping an open mind to what might lay ahead is admirable and inspiring. He was open to new developments in art and the new tools that might improve his work, even if it meant changing his methods of creation.

As McCay himself said: “For inventive genius ready not only to originate new ideas but capable of putting them into execution there is an almost untried realm of new possibilities . . .. Always try to do better.”

Bibliography:

Marschall, Richard. Dreams & Nightmares, The fantastic Visions of Winsor McCay, (California: Fantagraphics Books, 1988)

Canemaker, John, Winsor McCay, his life and Art. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers. 2005)

McCay, Winsor, Little Nemo 1905-1914 (USA: Oceanic Graphic Printings. 1993)

Web Sources:

Heer, Jeet. ‘The Dream Artist’, The Boston Globe, January 8, 2006.

(https://www.boston.com/news/globe/ideas/articles/2006/01/08/the_dream_artist/?page=full)